Roland Topor's Le Locataire chimérique (lit. 'The Chimerical Tenant') is translated into English as The Tenant, which is also the title of Polanski's 1976 film version of the novel: I think the reasoning must be that 'chimerical' is far too uncommon an English word for its use to be acceptable here.

This is quite an amazing book which I would hesitate to fit into any genre: it's not horrifying enough to fit into the horror category, but it's certainly too horrifying to fit into the humour category, although much of it is humorous (if mainly in a horrifying way). It is full of suspense, but mainly of a psychological nature: it appears to be an account of a man being driven mad, or driving himself mad, and that is very close to the truth, although there's a twist right at the end.

Trelkovsky is a young guy who has to find a new room and moves into one that he's not entirely happy with mainly because the W.C. is a fair way from it, but he has limited funds and accommodation isn't too easy to find. He learns that a girl, Simone Choule, was the previous tenant and for an unknown reason threw herself from the window and through the glass roof below. She's not dead but in bad shape, so he goes to visit her in hospital to find out if there's any possibility of her wanting to go back to her old place. In hospital he meets her friend Stella, with whom he strikes up a casual friendship, and later that day finds out that Simone has died.

Right from the start Trelkovsky strikes a bad note: he invites his friends from work in to celebrate his move, but they make such a noise that everyone in the building complains. From then on everything begins to go bad, and it seems that everyone is strongly against him.

To get an idea of how hypersensitive a person Trevelsky is (or has become), these few sentences – taken from about the middle of the novel – provide a good example: they describe the occasion when he sees Stella again with some of her friends and wants to talk to her, but he's unsure of how to approach her:

'What should he say? If he simply called her "Stella", wouldn't she find that too familiar? What would her friends think? And some people hate having their names called in a public place. Nor could he shout "Hey!" or "Hi!", that was too brash. He thought of "Excuse me!" but that was no better. Clapping his hands? Rude. Snapping his fingers? That was all right for waiters, but come on! He decided on coughing.' (My translation.)

And this is a girl he'd left the hospital with, had a drink with, went to the cinema with and whose generous breasts he eagerly investigated under her bra during the film, and who had no objection to his fondling her. (And incidentally, when he does renew his acquaintance with Stella they end up having sex the same day, but I should be ploughing on with the basics of the story.)

Things get increasingly worse for Trelkovsky, is the book in a nutshell. The animosity of the tenants and the owner M. Zy increase, and he's criticised for making the slightest noise. When his room gets burgled – his whole past taken from him, as he sees it – M. Zy hates the idea of him reporting it to the police and risk giving his business a bad name. His friends laugh at his seriousness and things get to such a state that he has no more social life, and wonders if he's going mad.

Certainly he's got a serious persecution complex, and he's obviously hallucinating about seeing Simone through the W.C. window in bandages, and this idea about the neighbours wanting him to turn into Simone, puting make-up on him, wanting him to kill himself, is plain crazy. So in desperation he escapes to Stella's place, and she welcomes him, but then he suspects she's in on the persecution game too so he steals what little money he can find of hers to stay in a hotel. And then – catastrophe – he's hit by a car, only has a few bruises, but is forced to return to his former accommodation, and in despair joins Simone by jumping out the window.

But she's not dead. She? Oh yes, that's what the nurses call him, and then there's Stella at his bedside saying 'Simone, Simone, do you recognise me?' Er, so was this all a dream in a coma? Or, as we know that 'Trelkovsky' also suffered from gender confusion, is he just Simone's alter ego, maybe a clue as to why she killed herself?

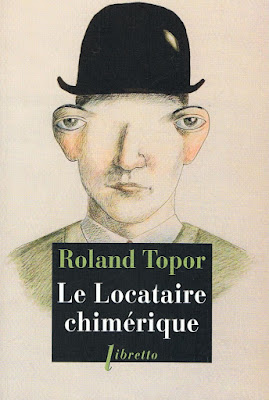

The above cover drawing is by Topor himself. Below is a link to my other post on him:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Roland Topor's grave, Montparnasse

This is quite an amazing book which I would hesitate to fit into any genre: it's not horrifying enough to fit into the horror category, but it's certainly too horrifying to fit into the humour category, although much of it is humorous (if mainly in a horrifying way). It is full of suspense, but mainly of a psychological nature: it appears to be an account of a man being driven mad, or driving himself mad, and that is very close to the truth, although there's a twist right at the end.

Trelkovsky is a young guy who has to find a new room and moves into one that he's not entirely happy with mainly because the W.C. is a fair way from it, but he has limited funds and accommodation isn't too easy to find. He learns that a girl, Simone Choule, was the previous tenant and for an unknown reason threw herself from the window and through the glass roof below. She's not dead but in bad shape, so he goes to visit her in hospital to find out if there's any possibility of her wanting to go back to her old place. In hospital he meets her friend Stella, with whom he strikes up a casual friendship, and later that day finds out that Simone has died.

Right from the start Trelkovsky strikes a bad note: he invites his friends from work in to celebrate his move, but they make such a noise that everyone in the building complains. From then on everything begins to go bad, and it seems that everyone is strongly against him.

To get an idea of how hypersensitive a person Trevelsky is (or has become), these few sentences – taken from about the middle of the novel – provide a good example: they describe the occasion when he sees Stella again with some of her friends and wants to talk to her, but he's unsure of how to approach her:

'What should he say? If he simply called her "Stella", wouldn't she find that too familiar? What would her friends think? And some people hate having their names called in a public place. Nor could he shout "Hey!" or "Hi!", that was too brash. He thought of "Excuse me!" but that was no better. Clapping his hands? Rude. Snapping his fingers? That was all right for waiters, but come on! He decided on coughing.' (My translation.)

And this is a girl he'd left the hospital with, had a drink with, went to the cinema with and whose generous breasts he eagerly investigated under her bra during the film, and who had no objection to his fondling her. (And incidentally, when he does renew his acquaintance with Stella they end up having sex the same day, but I should be ploughing on with the basics of the story.)

Things get increasingly worse for Trelkovsky, is the book in a nutshell. The animosity of the tenants and the owner M. Zy increase, and he's criticised for making the slightest noise. When his room gets burgled – his whole past taken from him, as he sees it – M. Zy hates the idea of him reporting it to the police and risk giving his business a bad name. His friends laugh at his seriousness and things get to such a state that he has no more social life, and wonders if he's going mad.

Certainly he's got a serious persecution complex, and he's obviously hallucinating about seeing Simone through the W.C. window in bandages, and this idea about the neighbours wanting him to turn into Simone, puting make-up on him, wanting him to kill himself, is plain crazy. So in desperation he escapes to Stella's place, and she welcomes him, but then he suspects she's in on the persecution game too so he steals what little money he can find of hers to stay in a hotel. And then – catastrophe – he's hit by a car, only has a few bruises, but is forced to return to his former accommodation, and in despair joins Simone by jumping out the window.

But she's not dead. She? Oh yes, that's what the nurses call him, and then there's Stella at his bedside saying 'Simone, Simone, do you recognise me?' Er, so was this all a dream in a coma? Or, as we know that 'Trelkovsky' also suffered from gender confusion, is he just Simone's alter ego, maybe a clue as to why she killed herself?

The above cover drawing is by Topor himself. Below is a link to my other post on him:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Roland Topor's grave, Montparnasse

No comments:

Post a Comment