Elements of the Southern Gothic are plentiful in Anne Tyler's Earthly Possessions. Charlotte says of her grotesquely obese mother: 'In some way, she'd grown separate from the rest of the town – had no friends whatsoever.' Added to that, her father 'Hung about as if he didn't own his own body [...] he looked like an empty suit of clothes'. And her mother said she didn't believe Charlotte was her real daughter, thought there'd been a 'mix-up' at the hospital. As a child, Charlotte's two principal fears were that she'd be rejected because she was not the real daughter, or that if she was the real daughter she wouldn't ever be able to escape.

Once again with Tyler, in this novel there's a statement that normalizes the abnormal, or abnormalizes the normal: 'Maybe all families, even the most normal-looking, were as queer as ours once you got up close to them.' What do you expect: this is Anne Tyler, who specializes in dysfunctional families and the weirdness of everyday life, who paints a world where the bizarre is an ordinary part of living. Several of Tyler's novels begin where a person walks out of a relationship, but in Earthly Possessions Charlotte Emory not only walks away from Saul to draw out money out of a bank for her escape, but at the same time walks into the clutches of bankrobber (and bad driver) Jake, whose almost consenting hostage she becomes, which begins an absurd road trip into Florida involving a mismatched couple, turning into a mismatched trio.

All this is told in two alternating first person narratives in the past tense by Charlotte, which are in fifteen sections – from the bank robbery through to the end of the road trip, and from Charlotte's early life up to the end of the road trip where the narratives converge – with a sixteenth section as a presentday coda. But Charlotte is still stuck in her past life, and things still happen to her without her being able to make anything happen for herself.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Anne Tyler: If Morning Ever Comes (1964)

Anne Tyler: The Tin Can Tree (1965)

Anne Tyler: The Clock Winder (1972)

Anne Tyler: Celestial Navigation (1974)

Anne Tyler: Morgan's Passing (1980)

Anne Tyler: Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant (1982)

Anne Tyler: The Accidental Tourist (1985)

Anne Tyler: Breathing Lessons (1988)

Anne Tyler: Ladder of Years (1995)

Anne Tyler: A Patchwork Planet (1998)

Anne Tyler: Back When We Were Grownups (2001)

Anne Tyler: The Amateur Marriage (2004)

Anne Tyler: Digging to America (2006)

Anne Tyler: Noah's Compass (2009)

Anne Tyler: The Beginner's Goodbye (2012)

Anne Tyler: A Spool of Blue Thread (2015)

Once again with Tyler, in this novel there's a statement that normalizes the abnormal, or abnormalizes the normal: 'Maybe all families, even the most normal-looking, were as queer as ours once you got up close to them.' What do you expect: this is Anne Tyler, who specializes in dysfunctional families and the weirdness of everyday life, who paints a world where the bizarre is an ordinary part of living. Several of Tyler's novels begin where a person walks out of a relationship, but in Earthly Possessions Charlotte Emory not only walks away from Saul to draw out money out of a bank for her escape, but at the same time walks into the clutches of bankrobber (and bad driver) Jake, whose almost consenting hostage she becomes, which begins an absurd road trip into Florida involving a mismatched couple, turning into a mismatched trio.

All this is told in two alternating first person narratives in the past tense by Charlotte, which are in fifteen sections – from the bank robbery through to the end of the road trip, and from Charlotte's early life up to the end of the road trip where the narratives converge – with a sixteenth section as a presentday coda. But Charlotte is still stuck in her past life, and things still happen to her without her being able to make anything happen for herself.

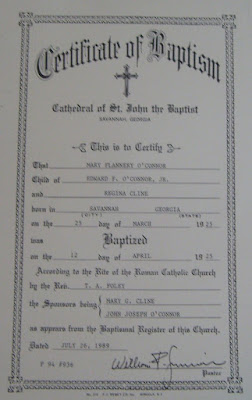

A criminal driving to Florida, a cat in a car? Isn't there just a teensie sniff of Flannery O'Connor's 'A Good Man Is Hard to Find' here? Tylerized, of course.The links below are to Anne Tyler novels I've written posts on:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Anne Tyler: If Morning Ever Comes (1964)

Anne Tyler: The Tin Can Tree (1965)

Anne Tyler: The Clock Winder (1972)

Anne Tyler: Celestial Navigation (1974)

Anne Tyler: Morgan's Passing (1980)

Anne Tyler: Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant (1982)

Anne Tyler: The Accidental Tourist (1985)

Anne Tyler: Breathing Lessons (1988)

Anne Tyler: Ladder of Years (1995)

Anne Tyler: A Patchwork Planet (1998)

Anne Tyler: Back When We Were Grownups (2001)

Anne Tyler: The Amateur Marriage (2004)

Anne Tyler: Digging to America (2006)

Anne Tyler: Noah's Compass (2009)

Anne Tyler: The Beginner's Goodbye (2012)

Anne Tyler: A Spool of Blue Thread (2015)