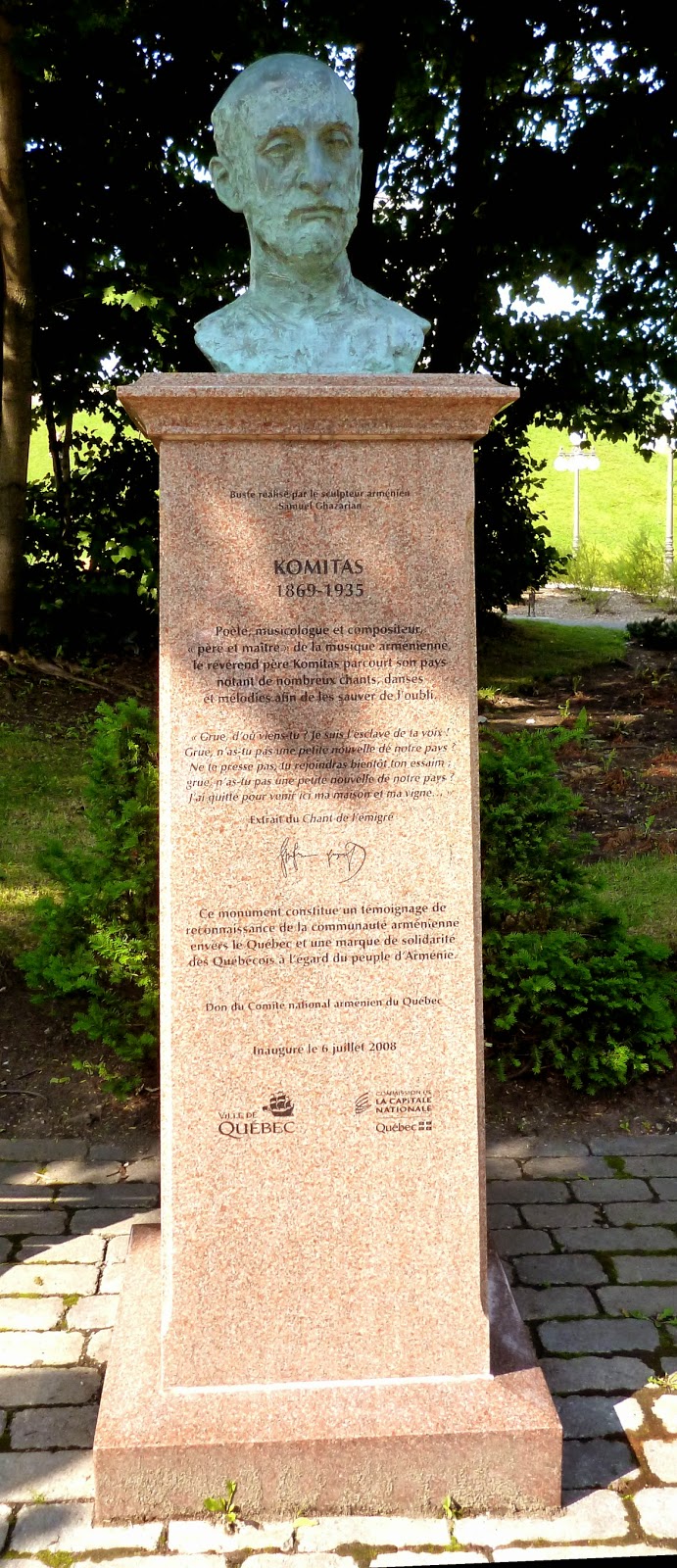

At the Place de la Gare in Québec is a sculpture by Michel Goulet, consisting of a large number of chairs, forty of which contain poetical quotations from forty writers associated with Québec. It was presented by Montréal to Québec on the 400th anniversary of the capital of the province in 2008. The title is Rêver le nouveau monde: literally, Dreaming the New World. (Yes, after a number of days of glorious sunshine came more than a little rain.)

The sculpture begins with the world under one – and a house under another – chair.

'rêver le nouveau monde'

'Ce soir

Le monde est vieux

Et je m'ennuie

Ann HÉBERT

(1916–2000)'

'une acceptation de l'absence

un renoncement à l'explication

une connaissance du vertige

un bonheur de la rencontre

Madelaine GAGNON'

'j'attends de naître

pour répondre à tes lettres

j'attends tes lèvres pour parler

Kim DORÉ'

'Irving LAYTON

(1912–2006)

The hills

remind me

of you

Not because they curve soft and warm

lovely and firm

But because

a long time ago

you stared at them

as I am staring now'

'Heureux qui dans ses vers sait, d'une voix tonnante

Effrayer le méchant, le glacer d'épouvante ;

Qui, bien qu'avec gôut, se fait lire avec fruit,

Et, bien plus qu'il ne plaît, surprend, corrige, instruit.

Michel BIBAUD

(1782–1857)'

'Malgré l'effarement

Malgré la lassitude

Des voix s'arrachent

Y-a-t-il une façon simple

D'ouvrir lHistoire

D'assécher les bourbiers'

Louise COTNOIR'

'Vient le jour où la beauté

borde notre chemin.

On se penche sur la vie, et aussitôt

on se relève, le coeur tremblant,

plus fort d'une vérité ainsi effleurée.

Hélène DORION'

'Nous avons partagé nos ombres

Plus que nos lumières

Nous nous sommes montrés

Plus glorieux de nos blessures

Que des victoires éparses

Alain GRANDBOIS

(1900–1975)'

'Elle ferme les yeux et rerêve:

c'était avant l'invention de l'écriture

Yolande VILLEMAIRE

'

'au bout de ce grand bout de terre

de peine et de misère

dis-moi

marie

pourquoi ce silence s'agrandit

Pierre PERRAULT

(1927–1999)'

'Mon désir parfois

ressemble aux dernières phrases

d'un livre

les livres n'ont pas de fin

les livres s'arrêtent

Normand DE BELLEFEUILLE'

'Le Cap Éternité

Témoin pétrifié des premiers jours du monde,

Il était sous le ciel avant l'humanité.

Charles GILL

(1871–1918)'

'Je dois tout dire dans une langue

qui n'est celle de ma mère.

C'est ça le voyage.

Dany LAFERRIÈRE'

'Toutes couleurs effacées.

Tous parfums supprimés,

Toutes paroles étouffées;

Muet et blanc,

Intolerable blanc,

Ce pays ne retient

Que les éclats du sang.

Gatien LAPOINTE

(1931–1984)'

'ne touchons pas au silence

il est notre réserve d'espoir

Nicole BROISSARD'

'Le monde ne vous attend plus

il a pris le large

le monde ne vous entend plus

l'avenir lui parle

Gaston MIRON

(1928–1996)'

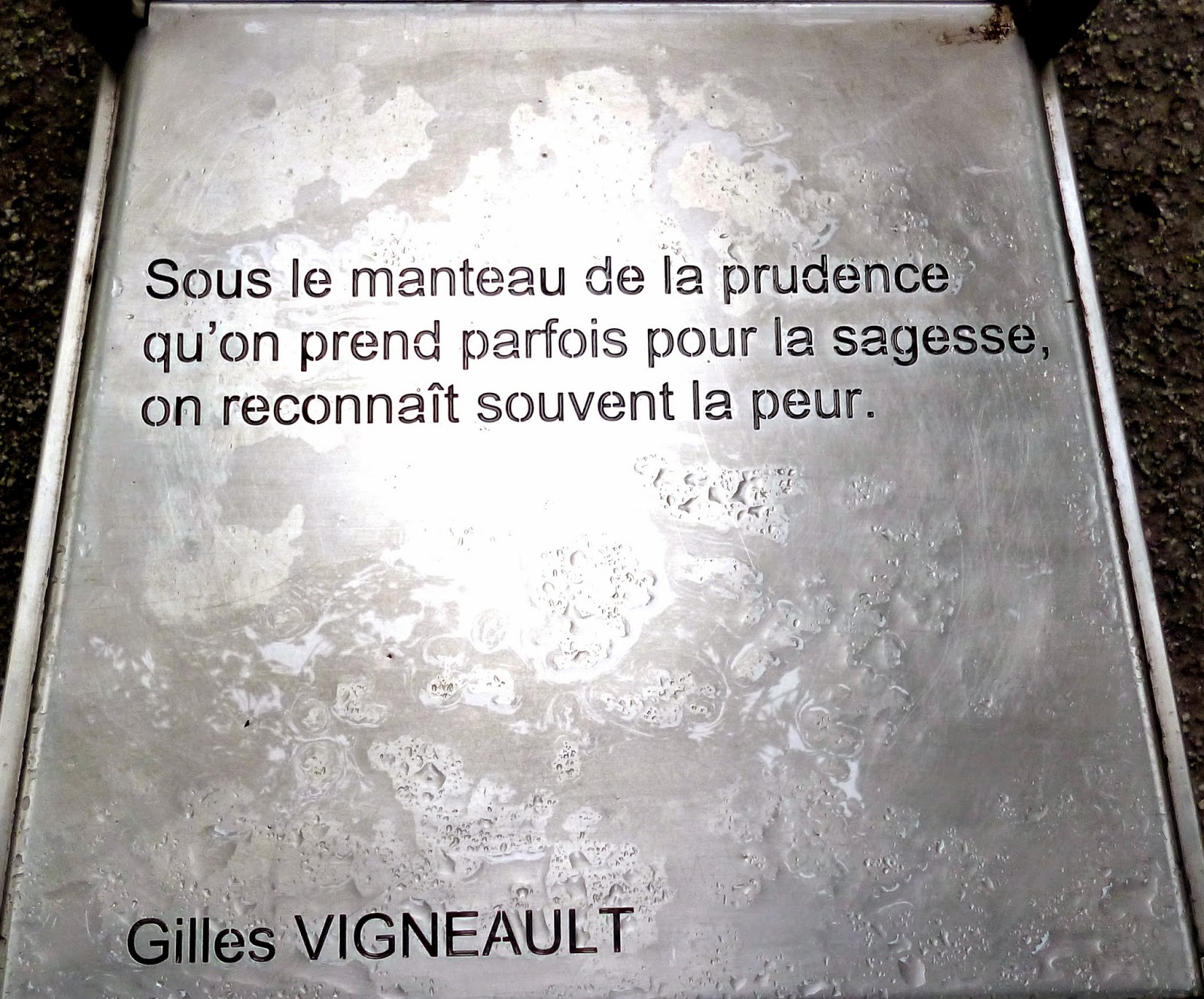

'Sous le manteau de la prudence

qu'on prend parfois pour la sagesse,

on reconnaît souvent la peur.

Gilles VIGNEAULT'

'J'aimerais rester dans l'ombre

dans ton ombre familière

le temps d'un hiver au moins

sinon d'une vie entière.

Roland GIGUÈRE

(1929–2003)'

'Dans les yeux s'allume une ville,

qu'on n'a jamais pris la peine de visiter.

Louise DUPRÉ'

'Le plus difficile c'est le premier siècle.

Rendu à trois, la racine est profonde.

Voilà ce que chantent les enfants

l'été

Félix LECLERC

(1914–1988)'

'Tu me manque

De toujours

Tu es l'ombre de l'Absente

Tu es ce passé sans toi.

Jean ROYER'

'Il est sur le sol d'Amérique

Un doux pays aimé des cieux,

Où la nature magnifique

Prodigue ses dons merveilleux.

Octave CRÉMAZIE

(1827–1879)'

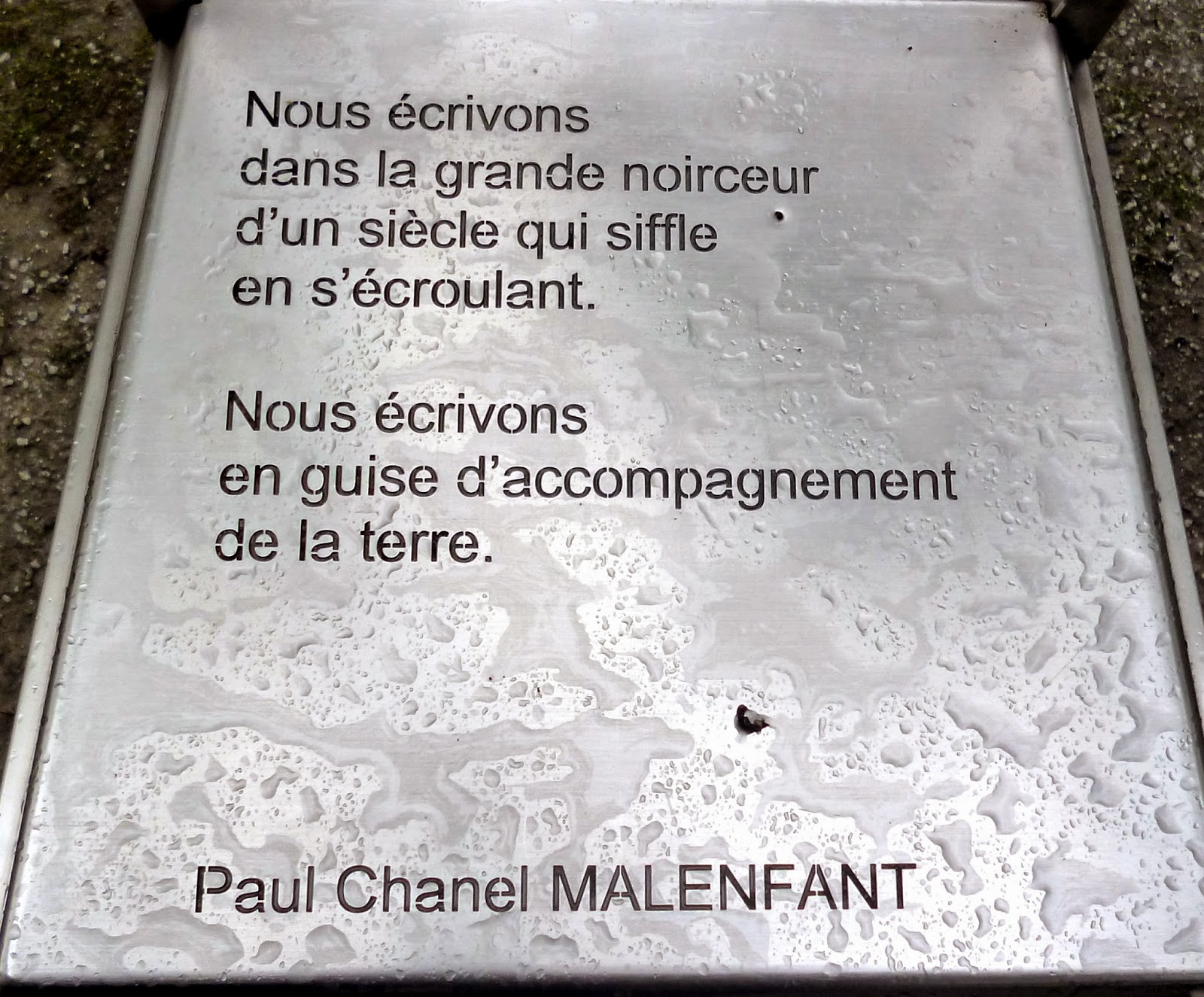

'Nous écrivons

dans la grande noirceur

d'un siècle qui siffle

en s'écroulant.

Nous écrivons

en guise d'accompagnement

de la terre.

Paul Chanel MALENFANT'

'...

veaux vaches cochons couvées

et préoccupations fi de vous et fi d'elles

à mon pays seul je suis fidèle

Gérard GODIN

(1938–1994)'

'Un enfant est en train de bâtir un village

C'est une ville, un comté

Et qui sait

Tantôt l'univers.

Il joue

Hector de Saint-Denys GARNEAU

(1912–1943)'

'La Mer navigue/

La Terre marche/

Le Ciel vole/

et moi, je rampe pour humer la vie...

Rita MESTOKOSHO'

'Je n'ai pas appris de Poucet

Le secret de marquer la route

Qui reconduise où l'on passait.

Alfred DESROCHERS

(1901–1978)'

This piece, concerning the sound of the Aurora Borealis, is written in Inuktitut by Emily Novalinga, who died the year after the artwork was created.

'Tu es la ville engloutie

sous les rumeurs pourtant je vois

il n'y a que toi parlant

et la passion que tu y mets

Hugues CORRIVEAU'

'Le travail n'est pas liberté

Le travail es dans la liberté

Claude GAUVREAU

(1925–1971)'

'L'homme...

Il se construit

Des milliers

Des millions

De milles

De câble blond

Et il leur a donné

Des millions

De milliers

De nœuds

Pour attacher la mer

Cécile CLOUTIER'

'Pleurez, oiseaux de février.

Au sinistre frisson des choses,

Pleurez, oiseaux de février,

Pleurez mes pleurs, pleurez mes roses,

Aux branches du genévrier.

Émile NELLIGAN

(1879–1941)'

'La nuit est une neige

qui tombe à l'envers.

Jean-Paul DAOUST'

'Il ne sait plus si sa propre mémoire

le garde vivant, si ses rêves

le nourisssent ou le dévastent.

Pierre NEPVEU'

'Je traversais sa nuit

et j'en rêvais le jour

je ne sais plus ce soir où va

la poésie

mais je sais qu'elle voyage

rebelle analogique

Claude BEAUSOLEIL'

'Petit jardin que j'ai planté,

Que ton enceinte sait me plaire !

Joseph QUESNEL

(1746–1806)'

'Hold me close

and tell me what the world is like

I don't want to look outside

I want to depend on your eyes

and your lips

Leonard COHEN'

'Seulement près de toy en cette saison dure.

Marc LESCARBOT

(1570–1642)'

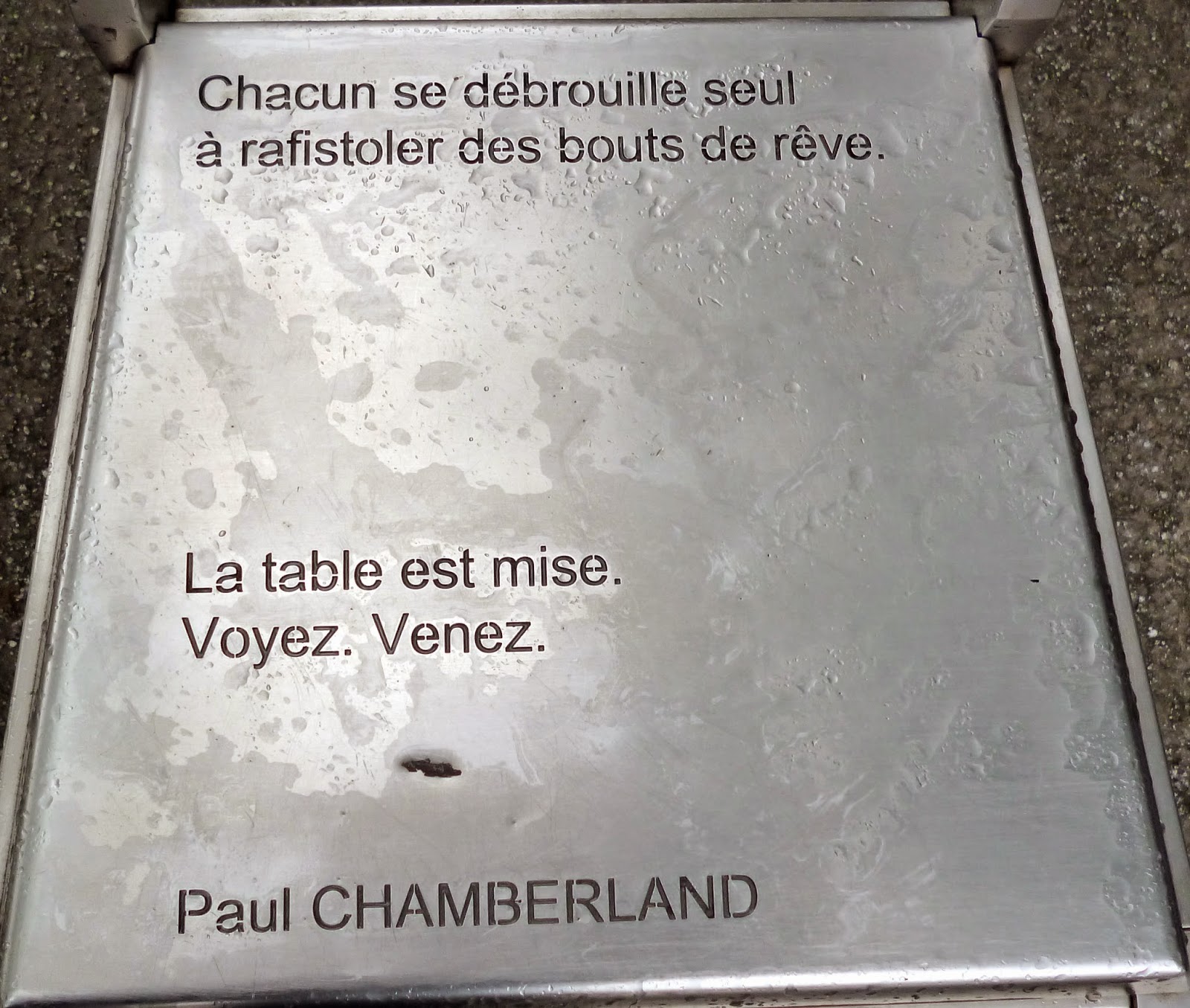

'Chacun se débrouille seul

à rafistoler des bouts de rêves.

La table est mise.

Voyez. Venez.

Paul CHAMBERLAND'

'Là où ses petites histoires,

mine de rien, s'emboîtent

les unes dans les autres.

Denise DESAUTELS'

At the end of all this is a two-paragraph description of the work by Michel Goulet:

'Pour ce quatre centiéme,

quarante chaises domestiques

créent un parcours

dans l'espace, le temps

et les pensées furtives.

Quarante voix poétiques disent,

le temps d'une pause, ce que nous

avons été, ce que nous sommes

et le bonheur de la rencontre.

Ici pas seulement des

spectateurs sollicités mais des

personnes qui prennent part

activement à la construction

d'un rêve en y jouant un rôle

essentiel, en faisant le trajet d'un

point à un autre, de la representation

géographique du fleuve qui

lie deux pôles du pays et l'ouvre

sur le monde et la représentation

de nos habitats fragiles, la Terre

et le domicile, ici, mis à l'abri.

M. Goulet, sculpteur'