I suspect that a major reason why Gallimard brought out this collection of all of the six novels that Boualem Sansal published before this year's 2084 is because they imagined that he'd win the Goncourt, and certainly it was a big shock for many people this Tuesday to learn that 2084 didn't even make it to the Goncourt's third selection. We may never know why, although it has been suggested that Sansal is perceived as an Islamophobe, which doesn't square with reality: he simply doesn't like Islamic excesses.

The six novels contained in this volume of more than 1200 pages tight pages are Le Serment des barbares (1999), L'Enfant fou de l'arbre creux (2000), Dis-moi le paradis (2003), Harraga (trans. as the same title) (2005), Le Village de l'Allemand, ou Le journal des frères Schiller (trans. as An Unfinished Business) (2008), and Rue Darwin (2011). Also here is an informative Preface by Jean-Marie Laclavetine, plus an even more informative potted and illustrated history of Boualem Sansal's life, with the history of Algeria from 1940 up to the present day.

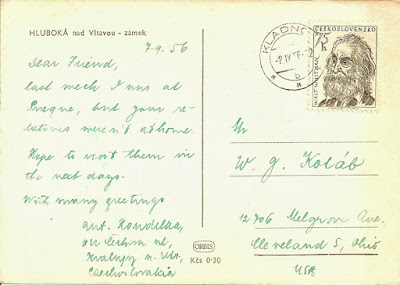

Sansal married a Czechoslovakian but a new law required that children of 'mixed' marriages be taught the Islamic religion. Sansal sent his two daughters back to Czechoslovakia to their maternal grandparents. The marriage ended in divorce in 1986, Sansal saying that his personal life had been ravaged by Islamists.

Sansal was also responsible for what he euphemistically calls the 'restructuring' (for which read privatisation) of the Algerian economy,* although in the same year his third novel was published he was dismissed from this post: he had gone too far in his criticisms of the chaos-ridden country Algeria had become in the years following its independence from France in 1962.

*Unfortunately Sansal is far from being a friend of socialism and sees it as outmoded, whereas many of us in western Europe have seen exactly how chaotic and socially unjust, for instance, the privatisation of public utilities actually is. In an interview, Sansal interrupted his interviewer because he used the expression 'selling off' ('brader') in relation to privatisation and claimed that the word was a hangover from the days of socialism. Enter 'restructuring', then, which to me seems almost to smack of the Orwellian 'Newspeak' Sansal so detests.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

But on to the first novel, Le Serment des barbares, which is a runaway train, or a whirligig, a linguistic roller coaster in which Sansal seems to be going out of his way to show his considerable learning on his sleeve. 'Rabelaisian' is one of the words that are often used to describe his work, and this novel (perhaps in particular, as I haven't yet read the rest) is a wonderful display of verbal pyrotechnics, using often very long digressive sentences often soaked in polysyllabic words, or Algerian words or terms both common and less common, or slang words, words for the love of words, often clothed in literary allusions.

All this to describe the chaos that Sansal now sees as Algeria, the political divisions within the country, the arabisation, more frequently the mindless violence, the wholesale slaughter, the misrule, the horror of daily existence. Perhaps most of all, the manufacture of ignorance: Sansal sees a triple illiteracy: the loss of French, the mis-teaching of Arabic, and the death of Kabyl and other native languages.

There's a detective story at the root of Le Serment des barbares, and the book begins in a cemetery, where two very different people are being buried: the very rich Moh who's a kind of godfather, and the poor Abdallah Bakour, both of whom have been violently murdered: the ageing police officer Larbi's job is to pursue the investigation into the Abdallah killing.

As Larbi makes his enquiries throughout the book – between the various tangents that Sansal digresses into – we inevitably learn about Abdallah's past. Until the year after Algerian independence he had been an agricultural worker for a French family in Algeria, and when they moved back to France he continued to work for the family: bosses had died and others taken their place, but he was still greatly respected by the family in his new home and had more or less been thought of as one of the family. He had refused to accept money to upkeep the family tomb when he returned to Algeria at the age of sixty-five, but maintained it freely, living in a very modest home near the Christian cemetery. He is in fact a kind of symbol, his double identity standing for the possibility of tolerance, bringing the torn parts of the country together.

Alas, Larbi – mockingly referred to as both Maigret and Columbo – is too good at his job. He knows there's something wrong, knows it defies common sense that this harmless, humble soul should be assassinated as if he's a gang boss, so what's it all about? He gnaws away at it, a dog digging up a bone, digging, now... it couldn't be that drugs and weapons are buried in the tombs and Abdallah...? Too late, cop.

This is a rant, but it's a hugely powerful one, a tour de force, a kind of masterpiece. Boualem Sansal enters the world of Francophone fiction like a verbal steam roller.

My other posts on Boualem Sansal:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Boualem Sansal: 2084 : La fin du monde

Boualem Sansal: Rue Darwin

Boualem Sansal: Le Village de l'Allemand

Boualem Sansal: Harraga

Boualem Sansal: Dis-moi le paradis

The six novels contained in this volume of more than 1200 pages tight pages are Le Serment des barbares (1999), L'Enfant fou de l'arbre creux (2000), Dis-moi le paradis (2003), Harraga (trans. as the same title) (2005), Le Village de l'Allemand, ou Le journal des frères Schiller (trans. as An Unfinished Business) (2008), and Rue Darwin (2011). Also here is an informative Preface by Jean-Marie Laclavetine, plus an even more informative potted and illustrated history of Boualem Sansal's life, with the history of Algeria from 1940 up to the present day.

Sansal married a Czechoslovakian but a new law required that children of 'mixed' marriages be taught the Islamic religion. Sansal sent his two daughters back to Czechoslovakia to their maternal grandparents. The marriage ended in divorce in 1986, Sansal saying that his personal life had been ravaged by Islamists.

Sansal was also responsible for what he euphemistically calls the 'restructuring' (for which read privatisation) of the Algerian economy,* although in the same year his third novel was published he was dismissed from this post: he had gone too far in his criticisms of the chaos-ridden country Algeria had become in the years following its independence from France in 1962.

*Unfortunately Sansal is far from being a friend of socialism and sees it as outmoded, whereas many of us in western Europe have seen exactly how chaotic and socially unjust, for instance, the privatisation of public utilities actually is. In an interview, Sansal interrupted his interviewer because he used the expression 'selling off' ('brader') in relation to privatisation and claimed that the word was a hangover from the days of socialism. Enter 'restructuring', then, which to me seems almost to smack of the Orwellian 'Newspeak' Sansal so detests.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

But on to the first novel, Le Serment des barbares, which is a runaway train, or a whirligig, a linguistic roller coaster in which Sansal seems to be going out of his way to show his considerable learning on his sleeve. 'Rabelaisian' is one of the words that are often used to describe his work, and this novel (perhaps in particular, as I haven't yet read the rest) is a wonderful display of verbal pyrotechnics, using often very long digressive sentences often soaked in polysyllabic words, or Algerian words or terms both common and less common, or slang words, words for the love of words, often clothed in literary allusions.

All this to describe the chaos that Sansal now sees as Algeria, the political divisions within the country, the arabisation, more frequently the mindless violence, the wholesale slaughter, the misrule, the horror of daily existence. Perhaps most of all, the manufacture of ignorance: Sansal sees a triple illiteracy: the loss of French, the mis-teaching of Arabic, and the death of Kabyl and other native languages.

There's a detective story at the root of Le Serment des barbares, and the book begins in a cemetery, where two very different people are being buried: the very rich Moh who's a kind of godfather, and the poor Abdallah Bakour, both of whom have been violently murdered: the ageing police officer Larbi's job is to pursue the investigation into the Abdallah killing.

As Larbi makes his enquiries throughout the book – between the various tangents that Sansal digresses into – we inevitably learn about Abdallah's past. Until the year after Algerian independence he had been an agricultural worker for a French family in Algeria, and when they moved back to France he continued to work for the family: bosses had died and others taken their place, but he was still greatly respected by the family in his new home and had more or less been thought of as one of the family. He had refused to accept money to upkeep the family tomb when he returned to Algeria at the age of sixty-five, but maintained it freely, living in a very modest home near the Christian cemetery. He is in fact a kind of symbol, his double identity standing for the possibility of tolerance, bringing the torn parts of the country together.

Alas, Larbi – mockingly referred to as both Maigret and Columbo – is too good at his job. He knows there's something wrong, knows it defies common sense that this harmless, humble soul should be assassinated as if he's a gang boss, so what's it all about? He gnaws away at it, a dog digging up a bone, digging, now... it couldn't be that drugs and weapons are buried in the tombs and Abdallah...? Too late, cop.

This is a rant, but it's a hugely powerful one, a tour de force, a kind of masterpiece. Boualem Sansal enters the world of Francophone fiction like a verbal steam roller.

My other posts on Boualem Sansal:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Boualem Sansal: 2084 : La fin du monde

Boualem Sansal: Rue Darwin

Boualem Sansal: Le Village de l'Allemand

Boualem Sansal: Harraga

Boualem Sansal: Dis-moi le paradis