'L'Île au trésor' obviously refers to Robert Louis Stevenson's book which appeals perhaps largely to younger people, and Brac also includes a quotation from the novel right at the beginning of this full-length documentary: '"I don't know about treasure," he said, "but I'll stake my wig there's fever here."' This is L'Île de loisirs at Cergy-Pontoise, where a large number of activities meet the gaze of the camera: a group of under-age kids trying to sneak in illegally; young women being chatted up; many water activities, some against the rules of the parc; a retired teacher staying in a five-star hotel and relating a story about a platonic relationship with two teenage girls; Afghan refugees talking about their experiences, etc. The young Guillaume Brac used to enjoy going to this place, as is obvious from the loving details he shows here.

31 March 2022

Guillaume Brac's Le Repos des braves | Rest for the Braves (2016)

This is a documentary on La Route des Grandes Alpes by cycle enthusiast Guillaume Brac. At the end of June each year about sixty retired amateur cyclists journey across the Alpes from the north to the south, to the Mediterranean shores in Nice and Menton, where they relax for a day before returning home. The route starts at Thonon-les-bains by the Lac de Genève and runs for about seven hundred kilometers. The tour lasts for four days and accommodation is prepared for them to spend the night. Along the way (of the film itself) are clips of Bernard Thévenet during Le Tour de France of 1975, and the gruelling Liège-Bastogne-Liège cycle run in the snow in 1980.

At the end, when the cyclists take their bikes to pieces and take the coach back, one of them has half-written a song to his Philippe cycle to the tune of Les Charlots's 'Merci Patron', which the others sing the chorus to, and which is followed by Brassens singing 'Heureux qui comme Ulysse', a hymn to freedom, travel, and Provence.

Guillaume Brac's Un monde sans femmes | A World without Women (2012)

This medium-length film takes place in Ault on the north coast, where a young-looking Patricia (Laure Calamy) and her late teenaged daughter Juliette (Constance Rousseau) go for a week's summer holiday, where the painfully shy middle-aged Sylvain (Vincent Macaigne) hands them the key. This is a quiet village where everyone knows each other, although Sylvain seems lost without a partner. The women, of course, are the centre of attention as Sylvain joins them on the beach, shows them how to fish, but is himself like a fish out of water.

Sylvain's attempts to hit it off with Patricia obviously aren't working, as proven by his aggression to the gendarme Gilles (Laurent Papot) who's taken her outside the disco for a snog against the wall. He's just one of nature's losers: how could he miss out on the signification the time Patricia sucked her finger when referring to Bill Clinton, for instance? Patricia, though, is really not interested in Gilles, not really interested in any man or woman sexually, she's just disillusioned by the whole thing.

However – and in a kind of reprise of the end of Brac's À l'abordage – and the viewer could see this coming by about the middle of the film – when Juliette comes to say goodbye to Sylvain the night before she and her mother are leaving she asks for his email address, eats strawberries with him and spends the night with him. She explains that her mother always goes for wrong type, the pushy ones, and it's clear that Juliette is more mature than her mother in a number of ways: the fact that Patricia wants to do a stupid multiple choice game in a magazine while Juliette's studying a book for college is just one of them. Refreshing, and of course Rohmerian at the same time.

26 March 2022

Terry Zwigoff's Ghost World (2002)

Ghost World is a world where smartphones have yet to be totally everywhere, but where retro is the new cool: cafés replicate the fifties, record players play vinyl, etc. Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) and Enid (Thora Birch) have graduated and, like, aren't too certain about the way their futures are gonna pan out, but hey, they don't want anything to do with dorks – although these are two cool girls surrounded by an uncool world. For the moment, though, Enid has to attend remedial art school, where the tutor was moulded by a (non-existent in real life) experimental film called 'Mirror, Father, Mirror', which could well be a piss-take of Stan Brakhage's Dog Star Man.

Then – and again this was made in 2002 so people still wrote small ads, like in the lonely hearts columns of newspapers – they notice one guy's ad (in fact from Seymour (Steve Buscemi), in his mid-forties). What a dork, and Enid writes this word in her diary. But then she starts to feel sorry for him as they've fixed him up with a totally non-existent date. So then they follow him, and Enid manages to talk to him at work: he sells secondhand records, and she even buys a blues record from him, one of the tracks of which she totally likes.

In fact she even sees him as cool. But then, of course, coolness can easily revert to uncoolness, and back again and back again, forever. But, like, Seymour's flat is so totally retro, he's even got an original(!) hook-up phone like you see in stone-age movies, and fifteen hundred 78s. Enid must fix him up with a girlfriend. But it's hard to talk about music to a girl when you know your subject inside out but she definitely doesn't. Yeah, any Aspie would be able to recognise that Seymour's on the spectrum.

But something of the Aspie gene dwells in Enid too. OK, you'd expect her not to relate to her father, but not to her best friend Rebecca. An old man, Norman, always sits on a bench on the sidewalk, waiting for a bus that'll never come because the service has been discontinued on this road. And yet we see Norman board an empty out-of-service one going – well, who knows? Ghost Town? So Enid decides to sit on the bench too, and another empty out-of-service bus pulls up for her. Un jour nous prendrons des trains qui partent. Totally weird, loved it.

Agnès Varda's T'as de beaux escaliers tu sais | You've Got Beautiful Stairs, You Know (1986)

The above photo is of course of Isabelle Adjani.

25 March 2022

Patricia Rosema's Mouthpiece (2018)

Mouthpiece illustrates grief in a very novel way. Elaine (Maev Beaty) was the daughter of Cassandra (Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava), and she has just died. Although there are various flashbacks, the two women playing Cassandra do not represent different states of Cassandra's life: they are in fact the two writers of the play on which the story is based, and they are presented as conflicts within Cassandra's psyche, within her grieving personality, also appearing simultaneously. For some time I was trying to figure out exactly what the two 'stood for' – mental versus physical, id versus superego? – but no, this is just a general personality conflict, I believe. And this is a very powerful film.

Agnès Varda's Du côté de la côte | Along the Coast (1958)

Although it was made twenty-eight years after Jean Vigo's À propos de Nice (1930), and although Varda directed Du côté de la côte commissioned by the tourist office, it is impossible not to view the two films side by side. Varda's work is by no means exlusively about Nice, although inevitably the town features strongly. La promenade des Anglais is of course present in both, as is the welcoming of visitors in cars as they roll up to the forecourts of expensive hotels, ditto the Grosses Têtes of the carnival. Obviously the clothes both on the beach and off are particularly starchy and formal in Vigo's film, but that's not the essential difference.

Varda's film is not without its humour: as she speaks about the tranquil spots the viewer sees hordes of tourists, and it is with obvious tongue firmly in cheek that she takes shots of every mention of 'Eden' that she can find: it's not too difficult to see the very subtle criticism of the mindlessness of tourism. Vigo, on the other hand, wasn't working to a commission, and could afford to show the other side of Nice: the poverty in the slums.

Neïl Beloufa's Occidental (2017)

This is artist Neïl Beloufa's second feature, and is set in an unknown period, although mobile phones are used. Two self-styled (but not for certain) Italians – Antonio (Idir Chender) and Giorgio (Paul Hamy) – book into the 'honeymoon suite' of a two-star hotel: gay they may be, although Giorgio starts flirting with the receptionist Romy (Louise Orry-Diquéro).

But the beginning is far from simple, in fact the whole film – with elements of a love story, a thriller, a comedy and maybe even a satire – is far from simple. Outside the hotel there is a riot, although the reason for it is unknown. There is prejudice in the hotel: homophobia, racism, ageism, etc. There's an overall stifling sense of pananoia and suspicion in most of the people in the hotel, and there are certainly misunderstandings. Diana (Anna Ivacheff), the hotel boss, thinks the 'Italians' are theives and calls the police: but as her suspicions are largely based on the fact that Antonio drinks Coco-Cola, which in her vast experience as a hotelier she thinks is very un-Italian, the police believe that there aren't enough grounds for arrest. But then they change their minds and think it's possible that they could be terrorists.

Towards the end the hotel catches fire and the guests have difficulty escaping: this is an extremely zany film in which the viewers' expectations are challenged all the way.

24 March 2022

Agnés Varda's Salut les Cubains (1963)

Salut les Cubains is Agnès Varda's love letter to revolutionary Cuba four years after the event. It shows the Cubans greatly praising Fidel Castro, and generally living their lives in celebration of the downfall of the dreaded Batista. But this (it is the wonderful Varda after all) is no mindless eulogy: what we have here is a secular hymn to Cuban culture in all its forms – the variety of the music, the literature, the architecture, the continuing ghost of Hemingway, etc. A glorious little film taken at the height of Cuban joy. Michel Piccoli is the voice.

Patricia Rosema's I've Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987)

Educated in Literature, Patricia Rosema's films sometimes announce the fact by their titles: the film But at My Back I Always Hear is of course a reference from Andrew Marvell's poem 'To His Coy Mistress', as 'I have heard the mermaids singing' is a reference from T.S. Eliot's poem 'The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock'.

But will the mermaids sing to Polly (Sheila McCarthy)? On the face of it it looks doubtful, and an employer once described her as 'organisationally impaired'. Right from the start, as Polly begins her first of several interruptions by narrative comment, we realise that this expression is a rather lame euphemism for Asperger's syndrome: socially, she's a failure, having no friends, in ten years since leaving home has only had a couple of very short-lived relationships, and a little into the film we discover that she is clumsy, awkward with machines as well as people, keeps saying the wrong things, and takes everything literally. She's a 'person Friday', but would anyone ever employ her permanently?

Well, yes, as Gabrielle (Paule Baillargeon) takes a liking to her and asks if she'd like to do secretarial work for her at her art gallery on a permanent basis: the deal is agreed to during a Japanese meal, when Polly is having an awful time trying to pick up food with a chopstick in each hand.

Patricia Rosema is openly lesbian, and her clumsy way Polly is kind of in love with, er, her angel Gabrielle. But disappointment comes when Mary (Ann-Mair McDonald) suddenly turns up, as she's a former (and much younger) lover of Gabrielle's.

I found the first half wonderfully fresh and arresting, although the second half plays down the Asperger elements which provided so much of the pleasure and humour. But the 'visions' (as Rosema calls them) run throughout, are far more than conventional reveries, and one of them concludes the film fittingly.

23 March 2022

Peter Mortimer in Sherwood, Nottingham

Thatcher's terrifying housing legacy extends far beyond council estates, reaches deep within new housing estates plagued by unbelievably rapacious management company leasehold (and fake freehold) charges, into any new estate which councils refuse to recognise, and her very black shadow is behind every legally extortionate (and very often sub-standard) new housing estate.

I doubt that Peter Mortimer is aware of this.

22 March 2022

Lytisha Tunbridge in Lenton, Nottingham

'Lenton Green

Green is the new gold fine woven through our community,

cross-stitched point to point by paths, plants, seats

where we greet and watch the world go by

powered by beams of sunlight, weft with windows bright

homes, each mesh grounded with garden or balcony of our own

here we all have a slice of the sky'

This rock is in a small space in a city suburb, and I was delighted to find it. Lytisha Tunbridge, Lenton poet, has published two 'pamphlets': Every Last Biscuit (2017) and A Backpack on his Backpack (2019). She has also made several online performances, and her work is in several anthologies.

Thomas Helwys in Lenton, Nottingham

20 March 2022

Julia Ducournau's Titane (2021)

I can't really see what all the fuss is about this film, which is undoubtedly extremely powerful but not, surely, a horror film? In a sense it's quite humorous, albeit in an absurd way: OK, a very absurd way. Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) as a child is involved in a car crash with her father, and as a result has a brain operation which involves a titanium implant. As she grows, things change, and her sexy contorsions at a car showroom with other young women to please customers – sex and cars, you know? – are just a beginning.

Her play-acting – which it isn't really – with cars lead her to admirers, have fans like a rock star. People, though, don't know that she's not into people: cars are (quite literally) her orgasm. And when one fan goes over the line and starts slobbering over her, he gets to meet her very strong hairpin: right through what little brain he has, via his earhole. And as the killings escalate, Alexia is wanted by the police and has to change her identity.

Titane is a film of several sexual identities: the regular heterosexual, the strong homosexual hints, the bisexual, and of course the sex with metal. Confusion reigns, and Alexia in a very powerful but untrue sense changes sex when she realises that she has to take on another identity: recognising that a missing boy strongly resembles her, this is her chance to become him, become Adrien. And as Adrien's father the pompier, who has far more problems than his lost son, is very gullible he comes to see Alexia as the missing Adrien.

Although he just wants to believe that a non-reality is a reality, in spite of others (including his former partner) realising that he's just fooling himself, and being fooled. Or is he? Isn't he merely knowingly pretending, isn't the ageing Vincent discovering new forms of sex and love, not really being self-deceptive? Irreality is the new real, and just look at Alexia's baby with the titanium studs in his back!

Céline Schiamma's Naissance des pieuvres | Water-lilies (2007)

Naissance des pieuvres is Céline Schiamma's first feature and is based on an exam script she made at the end of her Fémis studies. The title of the film is directly inspired by Violette Leduc's novel Thérèse et Isabelle. For Schiamma, 'the octopus is a monster growing in our bellies when we fall in love, a sea monster releasing its ink in us [...] so it's the birth of love at the age of adolescence' (my translation from the French Wikipédia).

I'd call it a teen sex flick with (almost) no sex, just three adolescents: Anne (Louise Blachère), who's very reluctantly verging towards the lesbian; Floriane (Adèle Haenel), who wants to try out Anne before going all the way with François (Warren Jacquin); and Marie (Pauline Acquart), who at first had the hots for François but then when he just lovelessly sheds his load in her, no way. Isn't adolescence hell?

Dorothy Whipple in Mapperley Park, Nottingham

'DOROTHY

WHIPPLE

Novelist

lived here from 1926 to 1939

"the fullest years of

my life"'

This plaque is on a house on Ebers Road, Mapperley Park, Nottingham. Dorothy Whipple (1893-1966) was born in Blackburn, Lancashire (where she died), and her novels are essentially about northern middle-class families and were popular in the 1930s an 1940s. They received an injection of life this century by Persephone, although Carmen Callil, the founder of Virago, revealed in 2008 that her publishing house used an expression: 'Below the Whipple line': 'We had a limit known as the Whipple line, below which we would not sink.' But how does a person determine 'level', whatever such an abstract concept means in literature?

19 March 2022

Leos Carax's Annette (2021)

It's easy to give a brief synopsis of Leos Carax's latest film Annette, which is in fact in English. Henry McHenry (Adam Driver) is a famous stand-up comedian with distinct echoes of Lenny Bruce*, whereas Ann Defrasnoux (Marion Cotillard) – the woman who'll shortly become his wife – is a famous opera singer. They have a child called Annette. As Henry loses his popularity he becomes jealous of Ann and takes to drink. To try to patch things up they go for a sailng holiday, but Henry gets drunk during a storm, tries to dance with Ann, and she falls overboard and drowns in the tussle. Henry saves Annette, they escape to shore, and there is no suspicion of foul play. Then Henry learns that Baby Annette can sing (wordlessly) and with the accompanist (Simon Helberg) they set about having her give huge performances to tumultuous reception. But then the accompanist tells Henry that he had an affair with Ann just before she formed a relationship with him and Annette might be his child: in a drunken rage Henry drowns him in the pool. But Annette has seen the murder, and in her final 'performance' all she can voice is 'Daddy...Daddy kills people.' So Henry is jailed.

There are many ellipses in the above paragraph, which in no way mentions the weirdness of the film, in which most of the dialogue is sung, with the story and lyrics mainly written by Ron and Russell Mael of the band Sparks: the brothers appear in the film, as does Carax himself at the beginning. And Annette is in fact a puppet who only appears as a human being at the end, when she visits Henry in prison. Several snatches from (performed) television broadcasts are seen, including one Ann dreams in which his former girlfriends accuse him of abuse. As the paparazzi hound the couple around the world, the toll this takes on a relationship can be felt. Is this movie a take on appearance and reality and the brittleness of fame, a criticism of the cult of celebrity, or all three and more? Whatever the unanswerable question, this is an electrifying spectacle.

*Henry's onstage behaviour is self-destructive, partly autobiographical, uses strong language, and for those who've seen Bob Fosse's Lenny will recognise familiarites between Dustin Hoffman and Adam Driver.

Ariane Labed's Olla (2019)

In movie terms, perhaps many people would associate Nevers with Alain Resnais's Hiroshima mon amour or possibly Éric Rohmer Conte d'hiver, but Ariane Labed's first movie, the twenty-seven minute Olla, is largely set in that city, and the eponymous protagonist, played by Romanna Lobach, enjoys a quiet moment in L'Église Sainte Bernadette du Banlay a few kilometres from the centre.

Olla is of east European descent, and has come to live with Pierre (Grégoire Tachnakian) after meeting him on an internet dating site. Pierre lives with his aged mother (Jenny Bellay), who is chairbound, never says anything, and is perhaps suffering from Alzheimer's disease. When Pierre is out at work, we see Olla dancing sexily in her underwear in front of the mother, masturbating in the kitchen, and charging the local guys thirty euros for a blow job and one hundred for full sex. But she shows very little or no interest in Pierre, which is hardly surprising because he has chosen – although she certainly hasn't – to unofficially Gallicise her name to Lola. But what is surprising – after Pierre decides that the only way he can get satisfaction is by raping her – is that she lights several cigarettes, puts the ashtray by the stove, turns the gas on, wheels the mother onto the pavement, and casually walks off with her the small suitcase she came with. A brilliant beginning for a film-maker.

18 March 2022

Jacques Tati's Playtime (1967)

How do you say 'drugstore' in French? 'Droogstore'. Nothing to do with Kubrick's (or Anthony Burgess's) Clockwork Orange, but everything to do with language mélange à la Christine Brooke-Rose, the insane multi-lingual meaningless non-communication which has always been Jacques Tati's forte. In Tatiland, different cultures meet but don't always correspond, don't understand each other. But then, neither do the old and the new, the old and the young, and yet: isn't the insanity we're talking about not only here and now, but very much more so since Tati's film in 1967?

Playtime is in a sense science fiction, but then so much science fiction is already with us: the world which Tati creates is so familiar. Admittedly, the high-power brush with the headlights seems beyond the beyond, but the multiple button pushing and automatism seem to resemble our computerised existence today; likewise the endless traffic queues, the obsession with taking (an inauthentic) photo every moment.

Glass is ubiquitous here, people bash their noses on it, it (very oddly) reflects the tour Eiffel, the Arc de Triomphe, the Sacré-Cœur, etc. Without any obvious political agenda, Tati turns this film into a huge criticism of the modern world, its uniformity, its mindlessness, its absolute wish to conform and not rebel, its maintenance of the status quo, in effect its insanity. More than ever, we need people such as Tati to tell people to understand where they're going wrong, what is happening to our world. This film is a masterpiece by a genius of the cinema.

17 March 2022

Maurice Pialat's L'Amour existe (1960)

Maurice Pialat's L'Amour existe is one his first shorts, and is a kind of documentary, a kind of social critique, but more of a poem, or a very poetical rant. It lasts a mere twenty minutes, and Pialat's words are spoken over a number of images of mainly the Parisian suburbs, as opposed to central Paris itself, by Jean-Loup Reynold. The first word is 'Longtemps', as if Pialat were pouring out his knowledge in Proustian fashion. But here is a knowledge of the suburbs of Paris, of the change that 'progress' has brought, the (not so attractive as in some parts of Paris) HLMs which block out the sunlight, the two-, three- or four-hour commute to work and back, the immigrant bidonvilles in Massy just three kilometres from the Champs-Élysées. In the bidonvilles is a 'Hotel Floride' which is either ironic, hopeful, or a joke on Pialat's part. Also ironic – and presumably a blackly humorous touch by Pialat – is the felled street sign 'Rue Oradour Glane', a reference to the Nazi massacre of the inhabitants in the village of Oradour-sur-Glane (Haute-Vienne) in the closing months of World War II.

There is a number of statistics here, such as there being only three per cent of working-class children at universities, of whom there are only one and a half per cent in Paris. The most devastating sentence in this wonderful work is 'De plus en plus la publicité prévaut contre la réalité' ('Increasingly, advertising triumphs over reality.') In our post-political internet age, this sentence rings far more true than when it was written more than sixty years ago. This is a wonderful work of immense anger.

Maurice Pialat's La Maison des bois 7 (1971)

Hervé in his step-family is a painful experience: he may get on well with Brigitte, but the others are a world away, full of a mentally constipated bourgeois urban existence that is far from the rural idyll which has been Hervé's life. Albert visits to tell of Jeanne's ill health, Hervé runs from his new home to see her on her deathbed, and as his father and step-mother come to take him back to Paris the series closes.

An expression I didn't know is 'faire chabrot', which has many dialectal variations, but refers to diluting the thick bottom content of a dish of soup with wine. It is apparently then often drunk straight from the dish, although Paul uses a spoon. He also uses a large quantity of wine: Paul's drinking is one of the criticisms of his wife Hélène, and (as a strong contrast to the life that Hervé has known at La Maison des bois) the relationship is far from idyllic. This is my first Pialat, and certainly won't be my last.

Conveniently, the French Wikipédia provides a précis of each episode, which I give at the bottom of each post here: as La Maison des bois deserves more than one long blog post, I make seven short ones.

Épisode 7

1 La tour Eiffel – 2 Hervé et sa belle-famille – 3 Hervé et Brigitte – 4 L’atelier d’ébénisterie – 5 La cartomancienne – 6 Faire chabrot – 7 Le père d’Hervé a disparu – 8 – Devoirs d’école – 9 La dispute – 10 Les confidences d’un père – 11 Le cauchemar d’Hervé – 12 Le petit déjeuner au lit – 13 Hélène et Brigitte – 14 Albert à Paris – 15 La fugue d’Hervé – 16 Maman Jeanne se meurt – 17 Les gendarmes enquêtent – 18 Hervé revient à la Maison des bois - 19 Le marquis raisonne Hervé – 20 Au chevet de Maman Jeanne – 21 Générique

Maurice Pialat's La Maison des bois 6 (1971)

The Armistice has come and it's a time of great rejoicing. But not for those who've lost loved ones, such as the Picard family, and the schoolteacher (Pialat himself) tries to teach his pupils that it's not just a time of celebration but of remembrance. Bébert and Michel leave with their mothers, and Hervé soon follows, with somewhat heavy heart. He's re-joining the father he hardly knew, to live with him in Paris with Hélène (Barbara Laage), his step-mother, and her child by her previous relationship, Brigitte (Brigitte Perrier).

Conveniently, the French Wikipédia provides a précis of each episode, which I give at the bottom of each post here: as La Maison des bois deserves more than one long blog post, I make seven short ones.

Épisode 6

1 La vie continue – 2 L’armisticide – 3 Vive la France – 4 Le champ d’honneur – 5 L’instituteur – 6 La cour de récréation – 7 Le cadeau du marquis – 8 Les filles – 9 Le départ de Bébert et Michel – 10 Hervé dans son nouveau costume – 11 La nouvelle famille d’Hervé – 12 La maison est vide – 13 Une nouvelle pensionnaire – 14 Hervé et Magali – 15 Leçon de géographie – 16 Les adieux d’Hervé – 17 Générique

Maurice Pialat's La Maison des bois 5 (1971)

Some of Pialat's scenes are an almost idyllic representation, such as the bathing episode, which is shot in long loving takes, as if in opposition to the war, as if (almost) that it doesn't exist. Then Paul (Paul Crauchet), Hervé's father, visits briefly. And, as Albert feared, Marcel is declared dead. The war may be nearing its end, but it will be a tragic one for the Picard family.

Conveniently, the French Wikipédia provides a précis of each episode, which I give at the bottom of each post here: as La Maison des bois deserves more than one long blog post, I make seven short ones.

Épisode 5

1 Génerique – 2 L’exode – 3 Retour à la Maison des bois – 4 Des nouvelles de Marcel – 5 Les collets – 6 Autour de la table – 7 Le braconnier – 8 Albert chez le marquis – 9 Le bain familial – 10 Des histoires d’enfants – 11 Le père d’Hervé en permission – 12 Le temps de la guerre – 13 Le père s’en va – 14 Courage Jeanne – 15 La tristesse

Maurice Pialat's La Maison des bois 4 (1971)

There are surely numerous criticisms of war in this series, and this is one of them. French soldiers arrive, pitch tent, the children befriend them, and in turn play at war. In a real war game in which a German aviator is killed, there is a very long shot of a French soldier guarding the body, and he is almost motionless but he seems to register boredom, embarrassment, and/or resignation: typically, and wonderfully, so Pialat.

This is what the teacher has his pupils intone by rote: 'La France est ma patrie. Je l’aime comme mon père et ma mère. Afin de lui prouver mon amour, je veux maintenant être un enfant laborieux et sage pour être, quand je serai grand, un bon citoyen et un brave soldat…' ('France is my country. I love it as my father and mother. In order to prove my love, I now want to be hard-working and good, to be, when I grow up, a good citizen and a brave soldier.' (My translation.)

Conveniently, the French Wikipédia provides a précis of each episode, which I give at the bottom of each post here: as La Maison des bois deserves more than one long blog post, I make seven short ones.

Épisode 4

1 L’arrivée des soldats – 2 Le bivouac – 3 Les enfants jouent à la guerre – 4 Hervé chez la femme de l’aviateur – 5 Maman Jeanne et les Parisiennes – 6 Jeu de quilles – 7 Repas du dimanche – 8 Hervé à la peche – 9 Hervé grondé – 10 À l’école – 11 Albert est de garde – 12 Un tour en avion – 13 Hervé chez l’aviateur – 14 Combat aérien – 15 L’avion abattu – 16 Générique.

Maurice Pialat's La Maison des bois 3 (1971)

Mme Latour (Micha Bayard) and Mme Pouilly (Marie-Christine Boulart), Michel and Bébert's mothers, arrive at an empty Maison des bois, obviously not knowing that their letters have been destroyed by a jealous Hervé. Meanwhile the Picard family enjoy a picnic which recalls Renoir's film Une partie de campagne (1936), which in turn recalls some paintings by Monet, Pialet having been a painter before he was a film director. Marcel leaves for the war.

Conveniently, the French Wikipédia provides a précis of each episode, which I give at the bottom of each post here: as La Maison des bois deserves more than one long blog post, I make seven short ones.

Épisode 3

1 Une messe – 2 La carriole – 3 Les Parisiennes attendent – 4 Le pique-nique – 5 Querelles de mères – 6 Partie de campagne – 7 L’attente à la Maison des Bois – 8 Chandelle ! – 9 Un malentendu – 10 Hervé s’explique – 11 Marcel prend un bain – 12 Marcel incorporé – 13 Tournée générale – 14 La fête dégénère – 15 Marcel part à la guerre – 16 Générique.

Maurice Pialat's La Maison des bois 2 (1971)

Hervé, in a conversation with the postman, learns that his father intends to re-marry. He destroys this and other letters which are addressed to his host family, and becomes familiar with the affable widowed Marquis (Fernand Gravey).

Conveniently, the French Wikipédia provides a précis of each episode, which I give at the bottom of each post here: as La Maison des bois deserves more than one long blog post, I make seven short ones.

Épisode 2

1 Générique – 2 Les pleurs d’une mère – 3 Scène au café – 4 Conversation avec monsieur le marquis – 5 Lettres du front – 6 Du plomb dans les fesses – 7 Albert tiré d’affaire – 8 L’arrivée des Parisiennes – 9 À la santé d’Albert – 10 Hervé à la table du marquis – 11 La lettre volée – 12 Catéchisme – 13 Les ambulances – 14 Générique de fin.

Maurice Pialat's La Maison des bois 1 (1971)

Coming after Pialat's first feature L'Enfance nue (1968) about a child in host families, it seemed normal that the director should be considered appropriate for this television series, which is in seven parts and in total lasts for more than six hours: this is therefore not a feature film, but stands outside the small total number of ten features which Pialat made, between L'Enfance nue and Nous ne vieillirons pas ensemble (1972). Pialat said on occasions that it is his best film, although – a little along the lines of the expression 'Bresson avant Bresson' – others think that Pialat's 'real' film-making began with Loulou (1980).

The first episode is understandably dedicated to exposition, and the setting is rural, in a village in L'Oise, and the time is during the 1914-18 war. Gamekeeper Albert Picard (Pierre Doris) and his wife Jeanne (Jacqueline Dufranne) have a young adult daughter Marguerite (Agathe Natanson) and son Marcel (Henri Puff), but also take in young children whose fathers are fighting and whose mothers have to work, although one of the three women – the mother of Hervé (Hervé Lévy) – has left home permanently. The other children, Michel (Michel Tarrazon) and Bébert (Albert Martinez), are visited regularly by their mothers at La Maison des bois.

In this first part the viewer sees and learns a number of things, such as: the village teacher (Pialat himself) at work; the death of the marquise in a road accident; the churchwarden's liking for the curé's wine.

Conveniently, the French Wikipédia provides a précis of each episode, which I give at the bottom of each post here: as La Maison des bois deserves more than one long blog post, I make seven short ones.

Épisode 1

1 Un soldat en permission – 2 Histoire de France – 3 La marquise est morte – 4 Le goûter à la confiture – 5 La famille Picard – 6 L’oiseau en cage – 7 Le vin de monsieur le cure – 8 Cérémonie mortuaire – 9 Un bon café – 10 Le facteur – 11 Les poules – 12 Jouer à la guerre – 13 Le terrain d’aviation – 14 Le bedeau et la bigote – 15 La chorale – 16 Le marquis et le cafetier – 17 Hervé au château.

13 March 2022

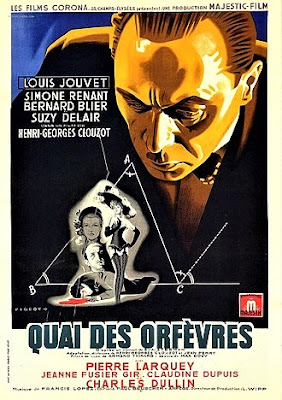

Henri-Georges Clouzot's Quai des Orfèvres (1947)

Henri-Georges Clouzot's Quai des Orfèvres is based on Stanislas-André Steeman's policier novel Légitime défense, and was the director's first film after his four-year prohibition following Le Corbeau (1943). The setting is very much the French music-hall world, with Jenny (Suzy Delair) the wife of Maurice (Bernard Blier), who is also her piano accompanist. And being set in this world, it is also a film of jealousy.

Without going too far into the complicated plot, Maurice is insanely jealous of the lecherous rich old man Brignon (Charles Dullin), who Jenny sees as a stepping stone out of music-hall parochialism and into the cinema. But unfortunately, Maurice has been heard yelling death threats to Brignon, which doesn't help when Brignon is found murdered and Inspector Antoine is called in to sort the matter out. Nor does it help Maurice's case that he went out to kill the already dead Brignon when he knew that he had invited Jenny to see him on the same night, and that Jenny thinks she killed him with a champagne bottle to thwart the old man's sexual advances.

And, Maurice's alibi hanging by a thread, he is inevitably arrested but attempts suicide. Then Jenny admits to murder, but so does the lesbian Dora (Simone Renant) who is in love with Jenny. But as Antoine says, he's in a similar position to Dora: they're both unscuccessful with women, and anyway he thinks he knows the real killer. Police treatment of its suspects is very far from depicted in a noble light in this film, but at least the real killer is found in the end: Paolo (Robert Dalban), the ferrailleur who came to burgle Brignon on the same night, but, seeing him injured by the champagne bottle, shoots him dead. Time for a reconcilation between Jenny and Maurice. I think the importance of this film in the history of French cinema in general has been a little overrated.

Henri-Georges Clouzot's La Terreur des Batignolles (1931)

With a script by Jacques de Baroncelli (Folco de Baroncelli's younger brother), this is Clouzot's first film, a fifteen-minute short made ten years before his first feature. And it contains a number of twists within that short time, the first giving the appearance of a film noir when in fact it's a comedy.

The burglar, the self-styled 'Terreur des Batignolles', is in fact hardly a terror, and his cowardice is soon witnessed by, on his having broken into a bourgeois appartment, his fear of a kitten. And then he's surprised when a couple in evening dress – Marianne (Germaine Aussey) and Robert (Jean Wall) – come in, so he hides behind a curtain. But Marianne noticed his feet – bootless as he has them round his neck so as not to make a noise – and they decide to play a game on him.

They pretend to be in a suicide pact, and as Robert closes the window and uses draught excluders for the door, the burglar is so frightened when Robert turns on the gas that he reveals himself. And here another twist is made as Robert robs him of the money in his wallet and Marianne takes his ring. As the burglar makes his exit there's another twist: the couple in evening dress are in fact burglars and Robert begins working on the safe. And La Terreur des Batignolles even finds that his watch has been stolen.

12 March 2022

Henri-Georges Clouzot's Les Diaboliques (1955)

Les Diaboliques is a kind of thriller with a horror-type ending and is a regular feature in most best French film lists. It was inspired by the novel Celle qui n'était plus (1952) by Pierre Boileau et Thomas Narcejac, and part of it (the 'murder' especially) is set in Niort, where Clouzot was born.

Essentially, there are four important characters here: Nicole (Simone Signoret), who works as Latin teacher in a private boarding school run by the tyrannical Michel Delassalle (Paul Meurisse), who is Nicole's lover and is married to the English teacher Christina (Véra Clouzot, the director's wife). The other person is Commissaire Fichet (Charles Vanel), on whom the eponymous detective in the American series Columbo (Peter Falk) is widely thought to be based.

Both Nicole and Christina detest Michel, who is not only violent towards them but callous towards his students, providing them with substandard food: this is ironic, though, as the money which oils the school's machinery comes from the very rich Christina. So they (or rather Nicole with the Catholic Christina's hypocritical agreement) decide to kill Michel: he is lured to Niort where he is put to sleep with a drug in his whisky which Nicole provides, and then (with Christina watching on) Nicole drowns him fully clothed in the bath. All that remains with the two women is to cart the body back in the school laundry basket and dump him in the school swimming pool.

But there's a problem: Michel has of course disappeared from school but even after the pool is drained he is not there: consternation for his women, and even more so when the suit he was wearing is delivered fully laundered by an outside firm. And to complicate things even further, there are reports of sightings of him in the school, even (it seems) in a new school photograph. Clearly, this is a case for Commissaire Fichet, who intervenes and carries out his own investigations, much to the fear of Nicole and Christina.

Christina has a weak heart and any disturbance can upset her, and it's hardly surprising that when she hears strange noises in the school late at night that she is very much alarmed. But her death blow comes when she sees her husband in the bath, rising as if from the dead and removing his false 'eyes of death': many viewers were stunned by this, so Christina's fatal collapse is understandable. And just as the two lovers Michel and Nicole prepare to celebrate their new fortune (Michel inheriting his late wife's wealth), Fichet immerges from the shadows to reveal that the sentence will be between fifteen and twenty years' imprisonment, depending on the skill of the lawyer.

10 March 2022

Robert Guédiguian's Lady Jane (2008)

Mercifully, this film doesn't include the song of the same name by the Rolling Stones, and coming from a person of Robert Guédiguian's staunch left-wing reputation I'd have been surprised (and very disappointed) if if had. No, Lady Jane comes from a tatoo of a marijuana leaf, with that name underneath: 'Mary Jane' (an old-fashioned name for marijuana) would perhaps have been more appropriate, but no matter.

The difference between this film and other Marseilles-based films by Guédiguian is that – although this is as usual about pals together – it's essentially a film noir: the three pals are (mostly) killers. There are two flashbacks which clue us in on the past, before the three – Muriel (Ariane Ascaride), François (Jean-Pierre Darroussin) and René (Gérard Meylan) felt obliged to go their separate ways. That was before the trio were into robbery (particularly fur coats), before Muriel killed a jeweller.

Now, Muriel has a boutique in Aix, François is in boat repair business, and René is a pimp with a striptease joint. They haven't met for years, until Muriel's son is kidnapped and a ransom demanded. So she meets her two former accomplices, they club together to pay the ransom, but that's not what was really wanted: the jeweller's young son had seen his father murdered (seeing the tatoo was the giveaway), and wanted Muriel to see what it feels like to have a loved one killed right in front of you.

In retaliation, the gang of course kidnap the former jeweller's son in turn, but already the trio has proved that violence merely begets violence, revenge is a one-way-street, so time for a rethink?

Robert Guédiguian's Le Promeneur du Champ-de-Mars | The Last Mitterrand (2005)

Robert Guédiguian moves away from the southern atmosphere of Marseilles, L'Estaque in particular, to make this wholly different feature in a sense of France in general. This film is an adaptation of Georges-Marc Benamou's novel Le Dernier Mitterrand, which of course gives it the English title. But in the original French version there is no direct mention of Mitterrand, although it is perfectly obvious that this is about the president's last days. Here, Mitterrand is wonderfully played by a seigneurial Michel Bouquet, and his (partly fictional) biographer Antoine Moreau by Jalil Lespert.

Although this is a film of two people, Antoine's personal life is understandably of little interest here. What matters is Mitterrand in the final weeks of his life. He has been president for fourteen years, the longest term of office that any French president has served. But what really matters here is not Mitterrand's politics, but a highly influential, highly educated and very well-read man in his final days.

We first see the man flying towards Chartres, making quotations from Péguy's 'Présentation de la Beauce à Notre Dame de Chartres', visiting the basilica in Saint Denis, and going to Brittany and Jarnac (where he was born and is buried). Locations don't necessarily make chronological sense, and nor do Mitterrand's quotations: from one viewpoint, this is a jigsaw, and Mitterrand isn't hagiographised by any means. He may try to tone down his claim that he's the last great French president and that after him only financiers and accountants will come (the end of history in other words), but he really means it.

Guédiguian himself tones down Mitterrand's involvement in Vichy, tones down Mitterrand's supreme hatred for (and at the same time role in) the destruction of communism. So what are we left with? An old man who's dying, needs help getting out of the bath by his biographer, and who has no good words about the presents he's received for his birthday.

So now he's gone – who, exactly – was Mitterrand?

9 March 2022

Quentin Dupieux's Daim | Deerskin (2019)

If this is Quentin Dupieux, it must be weird, really absurd. Yes, but the weird and absurd this time mainly come from one person: Georges (Jean Dujardin, in not one of his blockbuster roles, but as a loser as in Delépine and Kervern's I Feel Good). Georges, 44 years of age, is going mad and is first seen collecting an autoroute ticket with Joe Dassin singing 'Et si tu n'existais pas' in the background. Clearly, this is a film about existentialism.

Georges's wife has left him and he's creating a new role for himself in life, buying a hugely expensive deerskin jacket with a digital camcorder thrown in free. But his wife has frozen their bank account and the only collateral he can provide his hotel with is his wedding ring. The jacket is of vital importance as Georges sees it as a god, as if talking to him, but importantly telling him that he must destroy all other jackets in existence.

At the local bar Georges makes contact with Denise (Adèle Haenel) the barmaid, who's done some basic film editing and is really interested to learn that Georges (who has at least stolen a book on the cinema) is a film-maker. As Georges starts to educate himself as a 'director', he gives or sends his cassettes to Denise to edit, she gives him more money for his film, and it seems that his crazy stories about his professional life are being believed. But Georges's films depict real situations, and Denise wants to see more blood.

So Georges provides her with more (real) blood films, taking the jackets from his victims, but Denise (apparently knowing nothing of the murders) seems absolutely convinced about this film, and as she films him in a countryside setting, the father of a young boy who's been staring at Georges, and whom Georges has wounded with a stone, shoots him dead. Denise's reaction? She puts on his jacket.

Robert Guédiguian's Au fil d'Ariane (2014)

Au fil d'Ariane is initially described as 'une fantaisie'. Ariane (Ariane Ascaride) is preparing food on her birthday to get ready for the party, but although bunches of flowers arrive she keeps getting phone messages saying people – including her husband and children – won't be able to show up: in fact it looks like no one will. So she just decides to drive into town in her car: surely a crazy thing to do if she's drinking?

And then as she waits with others for the bridge to lower and the ship pass and everyone gets out of their cars and starts dancing to music someone's playing. She meets and gets talking to a motor-cyclist and goes off to a restaurant with him, but what happened to the car? At the restaurant she meets people such as Jack (Jacques Boudet) who pretends to be American, Marcial (Youssouf Djaoro) the souvenirs seller, and the owner Denis (Gérard Meylan), who's obssessed with Jean Ferrat.

But she seems to leave all too soon, and the taxi driver (Jean-Pierre Darroussin) takes her to the pound where her car's been put, but she can't pay to get her car back or pay the taxi driver as a thief comes along and takes her handbag. Out of reluctant charity the driver takes her back to the restaurant where the owner sets her on as a member of his staff. Marcial provides a boat for her to sleep in, and life is ecstatic: she loves talking to the restaurant tortoise, who even talks back to her in perfect French.

Then Ariane meets the taxi driver again, only he's turned into a suicidal actor – or is that part of the act? Certainly Ariane gets her wish to join in the act by singing on stage with the man with a rope round his neck, and the audience is so appreciative of her performance. And then she wakes up to see her husband (the taxi driver it seems) her children and all the other people we've seen in her dream.

This may not be one of Guédiguian's best films, but it's really refreshingly different from his others.

8 March 2022

Eric Toledano and Olivier Nakache's Samba (2014)

Samba is a weird mixture that doesn't exactly (to put it mildly) come off. But then I didn't really think Intouchables particularly wonderful: there's a gap between reality and fantasy that the co-directors don't seem to have grasped, although they've certainly grasped the money. That, I'm sure, is the crux of the issue. Samba (Omar Sy) is a guy from Senegal, living with his uncle, who appears to have settled down with a permanent job in France, although when he applies for a carte de sejour he's sent to a detention centre on a temporary basis. There, he meets volontary worker Alice (Charlotte Gainsbourg), who is, after some trauma. beginning to reintegrate with the world, and she begins to find a mutual attraction to Samba. Things don't begin to fall apart here, although in the end this film can't decide if it's about immigrants' problems or just chooses to be an unrealistic romantic comedy ducking all the real social problems. Which is a pity. I laughed out loud at times, but these issues are no laughing matter.

Marcel Carné's Les Portes de la nuit | Gates of the Night (1946)

Les Portes de la nuit is an adaptation of Jacques Prévert and Joseph Kosma's ballet Le Rendez-vous. Jean Gabin and Marlene Dietrich were originally intended for the main roles, but they turned them down and the then relatively unknown Yves Montand (as Diego) and Nathalie Nattier (as Malou Sénéchal) took their roles. The film was orignally not a success because too close to very recent memory, although this (Carné's last, and last with Prévert as screenwriter) is now generally recognised as being among Carné's best.

Destiny, or Fate, is personified here by Jean Vilar, who follows people around dressed as a tramp, and, being able to a certain extent 'read' the future but by no means alter it, warns or advises people of what would be best for them, as well he tells them what he sees is in sight for them.

This is 1945, the war continues for a short time but liberated Paris licks its wounds, still having problems with the collaborateurs and the black market. Destiny first meets Diego on the métro, gets off at his stop, and then helps the young Étiennette (Dany Robin) and Riquet (Jean Maxime). Diego has come to announce the death his Résistance partner Raymond (Raymond Bussières) to his wife Claire (Sylvia Bataille), although he's wrong about that as Raymond has excaped and is very much alive. So they go to a café-restaurant to celebrate the reunion and there Diego again meets Destin, who points out his future lover Malou, who's waiting in a car while her detested husband Georges (Pierre Brasseur) has a swift drink.

Also in the café is Malou's brother Guy (Serge Reggiani), whom Diego will later discover is the collabo who denounced him and Raymond. Malou, after telling Georges that she detests him, is already in her original neighbourhood and briefly returns to see her father M. Sénéchal (Saturnin Fabre), who lives in the same appartment block as Raymond, where Diego is spending the night after missing the last métro.

Drawn outside by Raymond and Claire's only son , the boy 'Cri-Cri' (Christian Simon), Diego comes to meet Malou, and they both fall for each other in a big way. However, Guy, after discovering that Diego has rumbled him, tries to get a drunken jilted Georges to kill him, although he succeeds only in Georges killing Malou. Guy walks to his death by an oncoming train, and a defeated Diego takes the métro in despair.

The main ray of hope is in the future, in the young lovers Étiennette and Riquet, who weren't old enough to understand the complexities of occupied France.

6 March 2022

Alain Chabat's Astérix et Obélix : Mission Cléopâtre (2002)

Astérix et Obélix : Mission Cléopâtre is an adaptation of the cartoon Astérix et Cléopâtre by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo (1963) and has a host of famous actors: Gérard Depardieu (Obélix), Christian Clavier (Astérix), Jamel Debbouze (Numérobis), Monica Bellucci (Cléopâtre), Alain Chabat (Jules César), Claude Rich (Panoramix), Gérard Darmon (Amonbofis), Édouard Baer (Otis), Isabelle Nanty (Itinéris), etc, etc.

The plot itself is quite simple. Wishing to prove to César the greatness of Egyptian civilisation, Cléopâtre decides to build a superb palace in the middle of the desert in three months. She appoints architect Numérobis to do this, promising to shower him in gold if he succeeds, but to throw him to the crocodiles if he fails. So he enlists the support of the druid Panoramix, maker of the magic potion, who comes to Egypt along with Astérix and Obélix, plus of course the dog Idéfix. And in spite of attempts to thwart Numérobis's plans by the older architect Amonbofis and the Romans, the palace is built in time to meet the deadline. But the story isn't really the main point of interest.

The most interesting thing about the film, at least for me, is the huge number of cultural references: cinema, music, art, television, literature, and so on, of which these are a few out of probably hundreds:

– A profile shot of Cléopâtre recalls Léonard de Vinci's Mona Lisa

– Three bearded workers, each holding a stone, is similar to ZZ Top with each holding a guitar

– César shapes a triangle with his finger, like Mia a square in Pulp Fiction

– Amonbofis and Numérobis fignting recalls the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

– A shot very realistically represents Géricault's painting Le Radeau de la Méduse

– 'Un cap ? … C’est une péninsule !': Obélix refers to Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac, and also Depardieu's own role in the film

– 'J'ai plus d'appétit qu'un barracuda' refers to the line in Claude François's song 'Alexandrie Alexandra'

– Amonfobis sees an Egyptian in a red and white striped tee-shirt: a reference to the cartoon Où est Charlie ?

– Astérix's 'Nous sommes ici par la volonté et en mission pour Cléopâtre', etc, parodies a 1789 speech by Mirabeau

– Barbe Rouge's 'C'est un fameux un mât, fin comme un oiseau, hissez haut !' is (almost) a direct quotation from Hugues Aufray's song 'Santiano'.

Astérix et Obélix : Mission Cléopâtre was a huge success both commercially and critically. And deservedly so: although it may share some features with the Hollywood blockbuster, it's probably much cleverer than any of them.

5 March 2022

Alain Guiraudie's Ce vieux rêve qui bouge (2001)

Ce vieux rêve qui bouge is perhaps best known as the medium length film which Jean-Luc Godard praised as the best film at the Festival de Cannes in 2001. I can understand why: this is a hymn to work, of rather the remains of it, and as such it's a rather rare film in that it shows people actually performiing actions at work, not stopping to talk but talking at the same time as they're working.

Jacques (Pierre Louis-Calixte) has come to the factory – which is closing down – to remove the last piece of machinery. We see him working on the machine, drinking with the workers, and showering at the end of the day. We also know that he's unmarried, is only attracted to men, and is sexually drawn to the pot-bellied boss Donand (Jean-Marie Combelles), who withdraws when (at the same time as he works) Jacques tries to pull his cock out.

On the final day, Jacques learns definitively that Donand really isn't interested. But Louis (Jean Ségani) – a man in his early fifties much weathered by work and appears considerably older than his years – tells Jacques that he gets a hard-on at the mere thought of him. But Jacques isn't interested, and no it's not his age or his figure, he just isn't interested.

And as the credits roll, a muscular-sounding male voice ensemble sings Théophile Gautier's 'Villanelle', a heterosexual pastoral song as the viewer sees an urban setting drift along.

4 March 2022

Quentin Dupieux's Mandibules | Mandibles (2020)

Grégoire Ludig (Manu in this film) and David Marsais (Jean-Gab here) are actors well known to a French-language viewer, but not to an Anglophone one, so a certain part of the humour will be lost: the duo are especially known for the Palmashow, of which the first television programme was La Folle Histoire du Palmashow (2010), and then the first feature film was Jonathan Barré's La Folle Histoire de Max et Léon (2016). Then came Mandibules.

This is, of course, an absurd film, but much funnier than Dupieux (aka musician Mr. Oizo) has come up with before. Manu and Jean-Gab are petty, thirtysomething crooks down on their luck, Manu out of work and sleeping on the beach, Jean-Gab still living with his mother. They've known each other for a long time, as witnessed by their constant 'Check taureau' signs, which mean everything and nothing. Manu has stolen a wreck of a car which he needs in order to deliver a small suitcase to the unknown Michel Michel, for which he'll receive five hundred euros, which is no doubt a large amount for a down and out. For some unknown reason – and here, perhaps, we're reminded of the frequent 'no reason' of Rubber – Jean-Gab is co-opted into the business.

They only have a half-hour drive to complete the mission, but a fly gets in the way, and not just any fly. This is a giant fly hollering in the boot of the stolen car, but (these guys are not on their uppers for nothing) Jean-Gab hits on an idea of brilliance: they can make much more than a measly five hundred balles, they can make a thousand times more by training the fly to be a drone, rob banks while they just do nothing: putain !

There are digressions, including very briefly living in a caravan which Manu by accident sets fire to, but they run out of petrol and Cécile (India Hair) mistakes Manu for a guy she knew in the past, and hey they have a place to stay in relative luxury. The trouble is not so much that brother Serge (Roméo Elvis) thinks they're a couple of débiles (brainless low-lifes in this case), but that they disturb Agnès (Adèle Exarchopoulos).

Agnès herself is disturbed, and as a result of a skiing accident can only scream instead of talk normally, but she also seems stricken heavily by paranoia. And although the buddies pass off this paranoia with impunity, they can't get away with it all the time, and after being rumbled by accident they hit the road (after syphoning some necessary gas).

So what can a fly do after being set free from the masking tape that holds down her wings: fly away, of course, and the buddies are about to happily re-begin their lives as losers, when she appears on the bonnet with the requested bunch of bananas. That's one very successfully trained fly. So what's next?

Yeah, I loved this.

2 March 2022

Marguerite Duras: Hiroshima mon amour (1960)

This book is mainly the screenplay of the Alain Resnais's film Hiroshima mon amour, which is essentially the same as the film. However, the Appendices are interesting, and shed light on the background of the film. Duras describes how the female progagonist, whose early life was spent in Nevers with her pharmacist father, came to meet her German lover: his arm was burned and he sought help, and the pharmacist's daughter cared for his wound on several occasions until he was completely cured. But then, the German followed her on her weekly bicycle rides to a farm for butter and they got to know and love each other in barns and bedrooms. He was her first sexual love, her first emotional love, until he was killed at the end of the war. The following lines reveal the extent of their love, and they intended to marry in Bavaria after the war:

'Son corps était devenu le mien, je n'arrivais plus à l'en discerner. J'étais devenue la négation vivante de la raison. [...]. Que ceux qui n'ont jamais connu d'être ainsi dépossédés d'eux-mêmes me jettent la première pierre' (My body had become his, I could no longer manage to tell the difference. I had become the living denial of reason. [...] Let those who have never known such dispossession of themselves cast the first stone.')

1 March 2022

Tim Burton's Edward Scissorhands (1990)

I first watched Edward Scissorhands some years ago, and was very impressed by its obvious metaphor for difference, although the difference I missed was Asperger's syndrome, which is of course written all over it: the isolation, the loneliness, the incomprehension of others, the hostility of those who for some reason want to entrap people of difference into a cage of normality. Edward Scissorhands (Johnny Depp) is the outcast who was created by an inventor (Vincent Price of horror film fame), who died of a heart attack before finishing his creation, leaving him with scissors for hands.

This is a great affliction and has caused Edward to self-harm by accident, and he's grown in the Gothic castle without human help, until (what could be more normal?) Avon representative Peg Boggs (Diane Wiest) comes calling and wants to fix his face. Introducing him to her initially sceptical family, they soon grow to love his kind ways, and he becomes a hit with most of the neighbours by his skills at topiary and cutting dogs' and humans's hair: Aspies often do have particular skills, either physical or mental, which can vary considerably.

Inevitably, though, his difference is not appreciated by everyone, and – Aspies being gullible as they tend to take everything literally – they are frequently not only the victims of jokes but are taken advantage of by others who use them to for their own purposes. Edward's love for Peg's daughter Kim (Winona Ryder) leads him into altercations with Kim's mindless boyfriend Jim (Anthony Michael Hall), trouble with the cops, and eventually the death of Jim and his retreat back to the castle. But Kim, now in love with Edward but knowing a relationship is impossible, says he's dead: she narrates her story as an old woman, with a strong hunch that Edward is still alive.

The film can be seen as a powerful plea for the understanding and acceptance of those on the spectrum, and a criticism of 'normality': there is a comical episode early on when the men leave their almost identical homes, get in their identical cars and drive to work at the same time – Aspies would laughingly describe this as NT (neurotypical) behaviour, and there's a great deal of this in Edward Scissorhands.

Robert Guédiguian's La Villa (2017)

Armand (Gérard Meylan), who runs a restaurant, and his brother Joseph (Jean-Pierre Darroussin), a former teacher and worker, still live in the area of L'Estaque just outside Marseille, where their sister Angèle (Ariane Ascaride), a noted actor now living in Paris, has come to join the two as their father Maurice (Fred Ulysse) is ailing. It might well be, though, that he'll carry on for some time almost as a cabbage in the villa. Angèle hasn't visited for many years, partly because she's reminded of her own mortality, partly because her young daughter Blanche died there.

Joseph lives with his much younger girlfriend Bérangère (Anaïs Demoustier), whom he met at univeristy and whom she was once inspired by, although it's obvious that the relationship is now in its final phase, it's played out much like Joseph, and soon the doctor Yvan (Yann Trégouët) will probably take his place and the younger pair will leave for Paris. Yvan is visiting his parents Martin (Jacques Boudet) and Suzanne (Geneviève Mnich), although they too are exhausted. Exhausted by their son's charity, but most of all exhausted by age and their stockpiling of medecines will lead to their joint suicide. It seems as though life is ebbing away from the community.

Certainly prices are rising, globalisation is destroying the old way of life, younger people – those with touristic or property interests – are increasing. And soldiers patrol the beaches and callanques to scoop up immigrants to take to holding centres to ship back.

But Angèle, who at first sees the advances of the much younger Benjamin (Robinson Stévenin), a local fisherman who's besotted by her acting and her fame – as crazy, soon succumbs to the illusion of prolonging her youth by welcoming him sexually. This may suggest something maudlin if it weren't for the young immigrants, a group of three kids, one (Haylana Bechir) several years older than her brothers (Ayoub Oaued and Giani Roux). She's been acting as a substitute mother, stealing bird food Armand has left in the wild, and jam from the villa. With this she keeps herself and her brothers alive, having built a shelter from branches and old clothing. Another young brother didn't make it and she's covered him with stones.

In a style reminiscent of Michel and Marie-Claire (also played by Darroussin and Ascaride) taking in the young brothers in Les Neiges de Kilimandjaro, Joseph and Angèle take in the three children, making sure the ever-prowling soldiers don't spy them. Life continues – no matter in what way – but its precariousness is ever-present.

Alain Resnais's Hiroshima mon amour (1959)

Alain Resnais and scriptwriter Marguerite Duras both agreed that it was impossible to make a film about Hiroshima, and this is the result. Everything is double, not only a collaboration between Resnais and Duras, but memory and forgetting, past and present, life and death, love and war, Nevers and Hiroshima, the personal and the collective, even the film really only has two human characters, male and female, Elle (Emmanuelle Riva) and Lui (Eiji Okada).

At the beginning we see two bodies (or shoulders of bodies), covered in the dust of the past, until the dust goes and we see two sweating bodies loving each other in Hiroshima: she is a French actor who has been visiting to make a film about peace in a city destroyed by hate, he is a Japanese architect or engineer who wasn't in Hiroshima at the time of the destruction. Both are married to another person.

There is archival footage of the former city, footage of the present rebuilt town in 1958, the museum, and shots of Nevers and its Place de la République where a street is now renamed after Duras and there's a plaque commemorating where the shooting took place. There are reconstructions of Nevers around the time that the bomb hit Hiroshima, when Elle's trauma serves as a personal microcosm of the collective trauma of Hiroshima: she had an affair with a German soldier who was killed, and she lay on his dying body all night, underwent the ritual of the 'tondues' by having her head shaved, rode all night on her bicycle to Paris, away from the traumatic memory. In the present, she says, she doesn't think about the past, although it haunts her in her dreams.

He is the only person she's told about the German and it's here where memory and forgetting merge into a paradoxical oneness. He wants her to stay but it's an impossibility, an impossible love, and this impossible film is one of the most important in the history of cinema.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)