'FRANK SARGESON (1903–1982)

lived at this address from

1931 until his death. Here

he wrote all his best

known short stories and

novels, grew vegetables

and entertained friends

and fellow-writers. Here

a truly New Zealand

literature had its

beginnings'

The original bach here, at 14 Esmonde Road (now 14A), was bought by Sargeson's (Davy) family in 1923 as a holiday home where they spent their Christmas summers. It was no more than a primitive one-room, creosoted shed. Sargeson came to live permanently here from May 1931, after leaving his uncle Oakley Sargeson's farm.

The new fibrolite dwelling above was built in 1948 by George Hadyn – Vernon Brown drew up the original plans, but the construction would have cost too much and Sargeson objected to the idea of a 'boogeois' (as he called it) terrazzo sinkbench.

The home Hadyn built had a living room-cum-kitchen at the front and a bedroom and bathroom with toilet at the back. This photo shows the original entrance, which was at the back and opened onto the bedroom. The wall on the right of the photo is part of the later extension – see below for more details. Bottom right is approximately the site of the destroyed ex-army hut.

The later entrance, with deck at the side of the original bedroom and additional bedroom to the back, was built in the late 1960s: Sargeson had inherited some money from his aunt Diana Runciman, who died in November 1966, and Sargeson's partner Harry Doyle – formerly frequently moving around – was living permanently with him now that he was becoming too ill for any more wandering.

Nigel Cook, who at one time had worked on Oakley's farm, was a practising architect living in Auckland, and he designed the extension. The top shelf of the bookcase holds numerous issues of the literary magazine Landfall. Sargeson used to have perishable food stored in the Tremains' fridge next door, but his aunt's death meant he could claim her old fridge for his dairy produce and cat food, etc.

The living room, with fitted bookcases, desk...

...and couch bed. Sargeson didn't like all the windows as it meant that he had to supply curtains for them.

On the other side of the living room is the kitchen, where Sargeson prepared his home-grown vegetables (although his garden shrank somewhat with the new property.)

Bob Gilbert (who as G. R. Gilbert had a brief writing life and was now working as a lighthouse keeper) built Sargeson a radio. He was delighted to listen to classical music on it, although it brought complaints from his neighbours.

The famous Lemora, an 18 per cent fortified grapefruit and lemon wine that Sargeson loved, and which he frequently shared with his friends. This was invented by the Russian immigrant Alexis Migounoff on his farm in Matakana and production went on for sixty years. In 2003, however, the government introduced a tax hike which would have meant an untenable increase on a flagon from $12 to $25. The New Zealand Herald (13 June 2003) reported that one angry Lemora drinker imagined Frank Sargeson rolling in his grave: this is doubly impossible, as he was cremated.

In 1950 Cristina Droescher (daughter of Greville Texidor) and her partner Keith Patterson (also known as Spud) were leaving for England and left Sargeson with Spud's paintings to brighten up his home.

Several other images hang on the walls: Sargeson and Harry Doyle.

On the porch bench Sargeson's hand rests on the black cat that walked into his life very shortly after Doyle left it, in 1971. With some hyperbole, he compared Robin Morrison's photo to an early Manet.

This delightful shot shows Janet Frame (1924–2004) tap-dancing in Sargeson's living room in 2000. It was taken by Michael King (1945–2004), both Sargeson's and Frame's biographer.

In 'The House That Jack Built', George Haydn's contribution to An Affair of the Heart: A Celebration of Frank Sargeson's Centenary (Devonport, NZ: Cape Catley, 2003), Hadyn speaks about the brief row he had with Sargeson over the shower room: Sargeson accused him of profiteering by skimping on materials, whereas Hadyn was in fact making a loss. (OK, I should have used flash.)

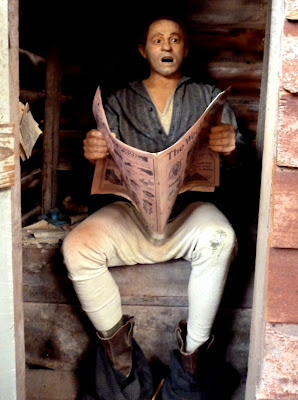

Hadyn also notes that Sargeson had an obsession with toilet pans: he held that high pans are 'completely unsuitable for natural crapping'.

The first bedroom, with the back door that was the entrance.

Sargeson's ashes, according to his wishes, were scattered under a loquat tree. Kevin Ireland marked the occasion by reading 'Ash Tuesday'.

'FRANK SARGESON

SCULPTURED BY

ANTHONY STONES

PRESENTED BY THE PEOPLE

TO THE

TAKAPUNA LIBRARY'

And in Auckland Central City Library is another likeness of Sargeson, this time by Alison Duff, 1965.

Many thanks to Vanessa Seymour of Takapuna Library for a very enlightening and fascinating tour of the Frank Sargeson house – and for mentioning this sculpture to us.

Link to another Sargeson post:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Michael King: Frank Sargeson: A Life (1995)