The cadran solaire de Dali (or Dali sundial) at 27 rue Saint-Jacques is a gift of Dali's to Paris. It represents the form of a coquille Saint-Jacques (scallop in English). The flaming eyebrows represent the sun's rays. It is probably the oldest route in Paris, having been used by pilgrims to Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle (Santiago de Compostela) in Galicia. In the bottom right-hand corner is Dali's signature and the date (1966) he made and erected the design.

11 December 2013

Immeuble Lavirotte in the 7th arrondissement, Paris

Libellés :

Lavirotte (Jules),

Paris

The magnificent art nouveau door at 29 avenue Rapp, dating from 1901 and by Jules Lavirotte (1864–1929). The door represents a design of a penis and testicles. Above the door itself are statues of Eve on the left and Adam on the right.

The bust immediately above the door is said to be a representation of Lavirotte's wife.

Élisa Mercœur in the 7th arrondissement, Paris

Libellés :

French Literature,

Mercœur (Élisa)

43 bis rue du Bac, where Élisa Mercœur died.

'ICI

HABITAIT ET MOURUT EN 1833 À 25 ANS

la Poètesse Nantaise

ÉLISA MERCŒUR

HABITAIT ET MOURUT EN 1833 À 25 ANS

la Poètesse Nantaise

ÉLISA MERCŒUR

HOMMAGE DU SOUVENIR LITTÉRAIRE

DE LA MUNICIPALITÉ

ET DE LA SOCIÉTÉ ACADÉMIQUE DE NANTES

DE LA MUNICIPALITÉ

ET DE LA SOCIÉTÉ ACADÉMIQUE DE NANTES

1935'

I had hoped to include the tomb of Élisa Mercœur in Père-Lachaise cemetery but didn't have time to look properly. I shall, I hope, add it next year.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Élisa Mercœur: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise

Louis Mandin in the 6th arrondissement, Paris

Libellés :

French Literature,

Mandin (Louis),

Paris

58 bis rue d'Assas.

Wikipedia states that Louis (born 1872) was one of the founders of La Vérité française, a secret newspaper of the Resistance which brought out thirty-two issues before they were arrested. At seventy-one, he was apparently beaten to death by a Polish inmate in 1843 in Sonnenburg prison. The page also notes that Marie-Louise died in Bergen-Belsen in 1945.

'À Louis MANDIN

Poète de "l'Aurore du Soir"

ET À

MARIE-LOUISE MANDIN

sa Femme

ARRÊTÉS PAR LES ALLEMANDS

LE 25 NOVEMBRE 1941

MORTS EN DÉPORTATION'

Poète de "l'Aurore du Soir"

ET À

MARIE-LOUISE MANDIN

sa Femme

ARRÊTÉS PAR LES ALLEMANDS

LE 25 NOVEMBRE 1941

MORTS EN DÉPORTATION'

Wikipedia states that Louis (born 1872) was one of the founders of La Vérité française, a secret newspaper of the Resistance which brought out thirty-two issues before they were arrested. At seventy-one, he was apparently beaten to death by a Polish inmate in 1843 in Sonnenburg prison. The page also notes that Marie-Louise died in Bergen-Belsen in 1945.

Leconte de Lisle in the 6th arrondissement, Paris

Libellés :

French Literature,

La Réunion,

Leconte de Lisle (Charles-Marie),

Paris

64 boulevard Saint-Michel, Paris.

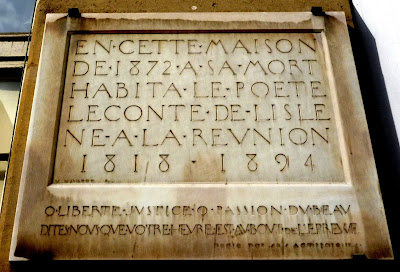

'EN CETTE MAISON

DE 1872 À SA MORT

HABITA LE POÈTE

LECONTE DE LISLE

NÉ À RÉUNION

1818 – 1894

Ô LIBERTÉ, JUSTICE, Ô PASSION DU BEAU

DITES-NOUS QUE VOTRE HEURE EST AU BOUT DE L'ÉPREUVE

Dédié par ses admirateurs'

Leconte de Lisle – a major figure in the Parnassian movement – was born in Saint-Paul, La Réunion, then called Île Bourbon, and died in Voisins, Yvelines. The poetical lines are taken from his Poèmes antiques (1852).

10 December 2013

Laurent Mauvignier: Des hommes (2009)

Libellés :

Algeria in literature,

French Literature,

Mauvignier (Laurent)

Much French literature has been written about World War One and World War Two, but very little about the Algerian War (1954–62). Laurent Mauvignier is a rare exception, and the Algerian War – its effects on those who took part in it and the effects on their families – is very much a part of the novel. Mauvignier's father was in it for twenty-eight years and killed himself when the author was an adolescent. Obviously he has no idea what part the war played in his father's suicide as he told him nothing about it, although his mother told him, for instance, that he was traumatised by seeing French soldiers trampling on a pregnant woman. His father brought back a large number of photos, although Mauvignier didn't know what they meant.

The unspoken, of course, is important to Mauvignier and is very much what the men in Des hommes carry around with them. This book attempts to give voice to the atrocies caused by this war, and by extension by war in general. Necessarily, it contains some horrifying scenes. And here, it's not the obvious provocative actions that can bring violence but the tiny, almost unseen and barely uttered actions and words.

As with other Mauvignier novels, there is a great deal of internal monologue here, and there are no markers for speech as the dialogue merges into the narrative. And a number of sentences remain either unfinished or are finished in the following sentence, which gives the narrative a greater realism.

Des hommes is divided into three main parts – 'Après-midi' and 'Soir' which are of equal length, and 'Nuit', which is the same length as the first two sections together. A fourth section – 'Matin' – is a kind of coda.

Bernard is now called Feu-de-Bois, an indication of how this old soldier – an alcoholic in his sixties – stinks. But this is the celebration of his sister Solange's sixtieth birthday in the reception room of the village with a number of his old soldier friends. His cousin Rabut does much of the narrating. I like the French expression péter un câble (something like 'bust a gasket'), which although not used here is what Feu-de-Bois does after the incomprehension that greets him giving Solange a very expensive brooch.

The 'Nuit' section is horrific and depicts, for instance, a French soldier shooting a fifteen-year-old boy through the head for no reason other than that he's old enough to be a 'terrorist', and the Algerian opposition stripping a living man's arm to the bone and massacring a village. No one is innocent in war is one chilling message.

But what exactly do the photos in Rabut's possession show of war, of the horror and fear? Nothing of it, only smiling faces, friends playing cards, the sea... Even those images betray nothing of the reality.

Like probably all of Laurent Mauvignier's books, this is amazing. He's definitely one of France's most significant living writers.

The unspoken, of course, is important to Mauvignier and is very much what the men in Des hommes carry around with them. This book attempts to give voice to the atrocies caused by this war, and by extension by war in general. Necessarily, it contains some horrifying scenes. And here, it's not the obvious provocative actions that can bring violence but the tiny, almost unseen and barely uttered actions and words.

As with other Mauvignier novels, there is a great deal of internal monologue here, and there are no markers for speech as the dialogue merges into the narrative. And a number of sentences remain either unfinished or are finished in the following sentence, which gives the narrative a greater realism.

Des hommes is divided into three main parts – 'Après-midi' and 'Soir' which are of equal length, and 'Nuit', which is the same length as the first two sections together. A fourth section – 'Matin' – is a kind of coda.

Bernard is now called Feu-de-Bois, an indication of how this old soldier – an alcoholic in his sixties – stinks. But this is the celebration of his sister Solange's sixtieth birthday in the reception room of the village with a number of his old soldier friends. His cousin Rabut does much of the narrating. I like the French expression péter un câble (something like 'bust a gasket'), which although not used here is what Feu-de-Bois does after the incomprehension that greets him giving Solange a very expensive brooch.

The 'Nuit' section is horrific and depicts, for instance, a French soldier shooting a fifteen-year-old boy through the head for no reason other than that he's old enough to be a 'terrorist', and the Algerian opposition stripping a living man's arm to the bone and massacring a village. No one is innocent in war is one chilling message.

But what exactly do the photos in Rabut's possession show of war, of the horror and fear? Nothing of it, only smiling faces, friends playing cards, the sea... Even those images betray nothing of the reality.

Like probably all of Laurent Mauvignier's books, this is amazing. He's definitely one of France's most significant living writers.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Laurent Mauvignier: Loin d'eux

Laurent Mauvignier: Apprendre à Finir

Laurent Mauvignier: Ceux d'à côté

Laurent Mauvignier: Dans la foule

Laurent Mauvignier: Tout mon amour

Laurent Mauvignier: Seuls

Laurent Mauvignier: Continuer

Laurent Mauvignier: Ce que j'appelle oubli

Laurent Mauvignier: Autour du monde

Laurent Mauvignier: Une Légère blessure

6 December 2013

August Strindberg and Marian Smoluchowski, 6th arrondissement, Paris

Libellés :

Paris,

Smoluchowski (Marian),

Strindberg (August)

60-62 rue d'Assas.

'En cet immeuble, alors hôtel Orfila,

l'écrivain suédois

August STRINDBERG

(1849 – 1912)

a vécu en février – juillet 1896

une phase décisive de sa vie.

l'écrivain suédois

August STRINDBERG

(1849 – 1912)

a vécu en février – juillet 1896

une phase décisive de sa vie.

"Orfila et Swedenborg, mes amis,

me protègent, m'encouragent

et me punissent. Je ne les vois pas,

mais je sens leur présence

ils ne se montrent pas à mon esprit, ni par

des visions, ni par des hallucinations,

mais les petits événements quotidiens

que je recueille manifestent

leur intervention dans les vicissitudes

de mon existence."

"Inferno", Mercure de France, Paris 1898.'

me protègent, m'encouragent

et me punissent. Je ne les vois pas,

mais je sens leur présence

ils ne se montrent pas à mon esprit, ni par

des visions, ni par des hallucinations,

mais les petits événements quotidiens

que je recueille manifestent

leur intervention dans les vicissitudes

de mon existence."

"Inferno", Mercure de France, Paris 1898.'

'ICI HABITAIT

M. SMOLUCHOWSKI

1895 – 1896'

Marian Smoluchowski (1872–1917) was a Polish physicist who was born in Vienna and died in Cracow.

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: La Tectonique des sentiments (2008)

Libellés :

French Literature,

Musset (Alfred de),

Schmitt (Eric-Emmanuel)

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt's play La Tectonique des sentiments is a homage to a section in Diderot's Jacques le Fataliste, which had already inspired Robert Bresson's film Les Dames du bois de Boulogne (1945), on which Bresson collaborated with Jean Cocteau.

The back cover of the book asks: Peut-on passer en une seconde de l'amour à la haine ('Can we go from love to hate from one moment to the next?'), and the answer to that can more or less be found in the title: Schmitt isn't interested in the gentle, idyllic shifts in love's nature as seen in Madame de Scudéry's Carte du Tendre, but in the violent seismic shifts of love's construction and destruction.

Richard is a rich businessman who is in love with the MP Diane, who is also in love with him. They see each other very regularly but don't live together, and although Richard has proposed to her several times, he hasn't done so recently and she feels that he must be tiring of her. When she confronts him with this he agrees with her and proposes that they stop being lovers but remain friends. What the audience doesn't know until near the end is that his pride won't allow him to say he feels just the same and really loves her, so the misunderstanding continues: Diane conceals her emotional pain and her wounded pride and turns it into desire for vengeance.

Diane is an MP with a specific interest in the position of women in society. She talks to two Romanian prostitutes: the first (Rodica) is getting past her prime; the other (Elina) is young and beautiful and has been lured to France with the promise of a university education, although she has no legal papers and has been tricked into prostitution. Within no time, Diane sorts things out legally, gets them off the game and provides them with an attic flat, although of course that comes at a price: that they have to befriend Richard, who needs someone to care for him as he only has months to live because he has cancer. He'll obviously be attracted to Elina, but Rodica (acting as Elina's mother) must fend off his sexual advances.

Richard falls hopelessly in love with Elina (who is also in love with him), but Rodica prevents him from seeing her and tries to give back his increasingly expensive presents to her. Nevertheless, the lovers occasionally clandestinely meet in a public park, although the relationship remains chaste. Even when Richard asks Elina to come and live with him Diane refuses to allow Rodica to let her guard down: Richard will die soon, has no one to leave all his money to, and Elina will be out on the street again when he dies.

And so Richard asks for the hand of the 'virgin' Elina, and it seems fitting that on their wedding day Diane (who doesn't attend) can hear a wedding song, whereas her mother thinks that on the contrary it's a war march.

On the morning after, while Elina is in bed, Diane visits Richard and asks him how the night was, and even if the sheets were bloodstained. Although affronted by the untimely intrusion and highly personal questions from his ex-lover, the new husband is more or less forced to agree that there was indeed blood. Diane tells him Elina has acted her part perfectly without a cue, whereupon she brandishes a dossier with the record of her soliciting, proof positive that she was a practising prostitute, and again we see a tectonic shift of feelings, and the marriage is over.

As the play states, in the emotional world you can't just press a 'Replay' button, at least not as far as Diane is concerned: she's the victim of her own machinations, and pride plays just as big a part in this. When Richard (who is of course in perfect health) finds out about the cancer scam from Rodica and on top of that learns that Elina really does love him, there's a tectonic shift back, although Richard won't unleash the full extent of his hatred for Diane by publicly revealing her treachery out of consideration for her mother, who (unlike Diane) is a good person. The only thing left for Diane is death, she feels.

The final scene is in a mortuary chapel, although it's not Diane's death but her mother's. Here, just before Richard leaves with Elina to begin a new life in another country, Diane accepts the situation and says she wishes Richard happiness. And as he leaves with his wife, he turns his head to Diane to say, his voice trembling with emotion, that he loves her, to which she replies that she loves him. He asks: 'Enfin?' 'Enfin...' 'At last?' 'At last...' (And those are the final words.)

Alfred de Musset is mentioned (by Elina) in this book, and the title of Musset's 1834 play On ne badine pas avec l'amour (a loose modern translation of which I would render as 'You Don't Mess Around with Love') would serve as a very good (but far too late) warning to Diane.

My Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt posts:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: La Nuit de feu

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: Milarepa

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: La Tectonique des sentiments

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: La Femme au miroir

The back cover of the book asks: Peut-on passer en une seconde de l'amour à la haine ('Can we go from love to hate from one moment to the next?'), and the answer to that can more or less be found in the title: Schmitt isn't interested in the gentle, idyllic shifts in love's nature as seen in Madame de Scudéry's Carte du Tendre, but in the violent seismic shifts of love's construction and destruction.

Richard is a rich businessman who is in love with the MP Diane, who is also in love with him. They see each other very regularly but don't live together, and although Richard has proposed to her several times, he hasn't done so recently and she feels that he must be tiring of her. When she confronts him with this he agrees with her and proposes that they stop being lovers but remain friends. What the audience doesn't know until near the end is that his pride won't allow him to say he feels just the same and really loves her, so the misunderstanding continues: Diane conceals her emotional pain and her wounded pride and turns it into desire for vengeance.

Diane is an MP with a specific interest in the position of women in society. She talks to two Romanian prostitutes: the first (Rodica) is getting past her prime; the other (Elina) is young and beautiful and has been lured to France with the promise of a university education, although she has no legal papers and has been tricked into prostitution. Within no time, Diane sorts things out legally, gets them off the game and provides them with an attic flat, although of course that comes at a price: that they have to befriend Richard, who needs someone to care for him as he only has months to live because he has cancer. He'll obviously be attracted to Elina, but Rodica (acting as Elina's mother) must fend off his sexual advances.

Richard falls hopelessly in love with Elina (who is also in love with him), but Rodica prevents him from seeing her and tries to give back his increasingly expensive presents to her. Nevertheless, the lovers occasionally clandestinely meet in a public park, although the relationship remains chaste. Even when Richard asks Elina to come and live with him Diane refuses to allow Rodica to let her guard down: Richard will die soon, has no one to leave all his money to, and Elina will be out on the street again when he dies.

And so Richard asks for the hand of the 'virgin' Elina, and it seems fitting that on their wedding day Diane (who doesn't attend) can hear a wedding song, whereas her mother thinks that on the contrary it's a war march.

On the morning after, while Elina is in bed, Diane visits Richard and asks him how the night was, and even if the sheets were bloodstained. Although affronted by the untimely intrusion and highly personal questions from his ex-lover, the new husband is more or less forced to agree that there was indeed blood. Diane tells him Elina has acted her part perfectly without a cue, whereupon she brandishes a dossier with the record of her soliciting, proof positive that she was a practising prostitute, and again we see a tectonic shift of feelings, and the marriage is over.

As the play states, in the emotional world you can't just press a 'Replay' button, at least not as far as Diane is concerned: she's the victim of her own machinations, and pride plays just as big a part in this. When Richard (who is of course in perfect health) finds out about the cancer scam from Rodica and on top of that learns that Elina really does love him, there's a tectonic shift back, although Richard won't unleash the full extent of his hatred for Diane by publicly revealing her treachery out of consideration for her mother, who (unlike Diane) is a good person. The only thing left for Diane is death, she feels.

The final scene is in a mortuary chapel, although it's not Diane's death but her mother's. Here, just before Richard leaves with Elina to begin a new life in another country, Diane accepts the situation and says she wishes Richard happiness. And as he leaves with his wife, he turns his head to Diane to say, his voice trembling with emotion, that he loves her, to which she replies that she loves him. He asks: 'Enfin?' 'Enfin...' 'At last?' 'At last...' (And those are the final words.)

Alfred de Musset is mentioned (by Elina) in this book, and the title of Musset's 1834 play On ne badine pas avec l'amour (a loose modern translation of which I would render as 'You Don't Mess Around with Love') would serve as a very good (but far too late) warning to Diane.

My Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt posts:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: La Nuit de feu

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: Milarepa

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: La Tectonique des sentiments

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: La Femme au miroir

5 December 2013

Marie d'Agoult: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #10

Libellés :

Agoult (Marie de Flavigny),

Balzac (Honoré de),

French Literature,

Goethe

The tomb of Marie d'Agoult (1805–76), who also wrote under the pseudonym Daniel Stern (as recognised here). Agoult is noted for her (sometimes stormy) relationship with George Sand, and for her depiction as Béatrix in Balzac's Béatrix (1839).

Goethe appears prominently in the background here: Agoult is noted for her writing on Dante and Goethe.

Link to my earlier post on Père-Lachaise:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Frédéric Beigbeder: Un roman français (2009)

Libellés :

Beigbeder (Frédéric),

French Literature

As the title of Frédéric Beigbeder's book Un roman français says – in fact twice, as the subtitle is 'roman' – this is a novel. As opposed to an autobiography, although there is a strong amount of autobiographical detail in this. Many novels are full of autobiographical detail of course, although this one has the narrator – the central character – with the same name and exact date of birth as the author, whose parents and whose brother also have the same name as Beigbeder's parents and borther, and Beigbeder (the author) was also arrested for hoovering up coke from the bonnet of a car in the early hours of the morning, etc. But this is definitely a novel, and for instance contains imaginary dialogue between the author's maternal grandparents (who sheltered a family of Jews in World War II), and other dialogue (particularly with the police, for instance) must be invented.

Beigbeder – who claimed still to be an adolescent in the non-fictional work Premier bilan après l'apocalypse, written a few years after this novel – in fact claims here that he grew up (at the age of forty-two) in the tiny, filthy police cell he was put in after the coke incident in which his friend (just called le Poète in the novel but Simon Liberati in real life) was also arrested for the same activity. The novel is a splendid opportunity for Beigbeder – the narrator of course – to release a stream of invective against the primitive prison conditions he has experienced, and he spends a few pages dwelling on the squalor witnessed, although it isn't without humour – such as that found in the occasional camaraderie among others detained there.

As we can expect from Beigbeder, there are a large number of literary allusions, such as from the ununiformed police officer, who mentions – and I suspect not only improbably so to Beigbeder but also to the reader – that Jean Giono first got the idea for Le Hussard sur le toit in prison. This comes after Beigbeder declares (in an equally improbable moment, although improbable for a very different reason) that the coke snorting was a homage to a chapter in Bret Easton Ellis's Lunar Park, which has Jay McInerney snorting a line from a Porsche hood in Manhattan: he says McInerney claimed that Ellis invented the incident, although Beigbeder believes it is true. Then Beigbeder gives the cop a list of writers who have been imprisoned, tossed off as if he carries the information around in his head, a kind of walking literary Wikipedia.

It isn't the memory he has of writers which is important in this novel, though, but the memory he doesn't have of the first fifteen years of his life. But – in Proustian outpourings – this is essentially what Un roman français is concerned with: unable to sleep, lacking any intellectual stimulation in his cell, Beigbeder cures himself of his amnesia by writing a novel about his and his family's history – but in his head because he might inflict harm on himself if he were allowed to have a writing implement.

So Beigbeder delves deeply within his past, from the little he knows of his great-grandparents, through to his grandparents, his parents meeting in Guéthary in the Basque country (the place where, he mentions, the poet Paul-Jean Toulet is buried), to his slightly older brother Charles, the trauma of their parents' divorce, his own intellectual history, his repetition of broken family histories by getting divorced twice, etc.

I was impressed by the way Beigbeder tries to reinvent Freudian analysis not through the parents but through siblings, in his case through his relationship with his brother, developing an identity by behaving in exactly the opposite way towards ideas and interests as Charles does.

And a sentence about childhood is worth thinking about: 'On n'évolue pas, l'enfance nous définit pour toujours puisque la société nous a infantilisés à vie. ('We don't evolve, childhood defines us forever because society has infantilised us for life').

Yes. A fascinating – and healthily honest – read.

Links to my other Beigbeder posts:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Frédéric Beigbeder: Mémoires d'un Jeune Homme Dérangé

Frédéric Beigbeder: 99 Francs

Frédéric Beigbeder: Premier bilan après l'apocalypseBeigbeder – who claimed still to be an adolescent in the non-fictional work Premier bilan après l'apocalypse, written a few years after this novel – in fact claims here that he grew up (at the age of forty-two) in the tiny, filthy police cell he was put in after the coke incident in which his friend (just called le Poète in the novel but Simon Liberati in real life) was also arrested for the same activity. The novel is a splendid opportunity for Beigbeder – the narrator of course – to release a stream of invective against the primitive prison conditions he has experienced, and he spends a few pages dwelling on the squalor witnessed, although it isn't without humour – such as that found in the occasional camaraderie among others detained there.

As we can expect from Beigbeder, there are a large number of literary allusions, such as from the ununiformed police officer, who mentions – and I suspect not only improbably so to Beigbeder but also to the reader – that Jean Giono first got the idea for Le Hussard sur le toit in prison. This comes after Beigbeder declares (in an equally improbable moment, although improbable for a very different reason) that the coke snorting was a homage to a chapter in Bret Easton Ellis's Lunar Park, which has Jay McInerney snorting a line from a Porsche hood in Manhattan: he says McInerney claimed that Ellis invented the incident, although Beigbeder believes it is true. Then Beigbeder gives the cop a list of writers who have been imprisoned, tossed off as if he carries the information around in his head, a kind of walking literary Wikipedia.

It isn't the memory he has of writers which is important in this novel, though, but the memory he doesn't have of the first fifteen years of his life. But – in Proustian outpourings – this is essentially what Un roman français is concerned with: unable to sleep, lacking any intellectual stimulation in his cell, Beigbeder cures himself of his amnesia by writing a novel about his and his family's history – but in his head because he might inflict harm on himself if he were allowed to have a writing implement.

So Beigbeder delves deeply within his past, from the little he knows of his great-grandparents, through to his grandparents, his parents meeting in Guéthary in the Basque country (the place where, he mentions, the poet Paul-Jean Toulet is buried), to his slightly older brother Charles, the trauma of their parents' divorce, his own intellectual history, his repetition of broken family histories by getting divorced twice, etc.

I was impressed by the way Beigbeder tries to reinvent Freudian analysis not through the parents but through siblings, in his case through his relationship with his brother, developing an identity by behaving in exactly the opposite way towards ideas and interests as Charles does.

And a sentence about childhood is worth thinking about: 'On n'évolue pas, l'enfance nous définit pour toujours puisque la société nous a infantilisés à vie. ('We don't evolve, childhood defines us forever because society has infantilised us for life').

Yes. A fascinating – and healthily honest – read.

Links to my other Beigbeder posts:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Frédéric Beigbeder: Mémoires d'un Jeune Homme Dérangé

Frédéric Beigbeder: 99 Francs

Frédéric Beigbeder: L'Amour dure trois ans | Love Lasts Three Years

3 December 2013

Charles Nodier: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #9

Libellés :

Blavier (André),

French Literature,

Nodier (Charles),

Queneau (Raymond)

'CHARLES NODIER

MEMBRE

DE

L'ACADÉMIE

FRANÇAISE

ET DE

LA LÉGION D'HONNEUR

BIBLIOTHÉCAIRE

DE L'ARSENAL'

The Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal is part of the BNF. Charles Nodier (1780–1844) was a highly prolific writer of the period, but for me he is particularly interesting for his 1835 book Bibliographie des fous : De quelques livres excentriques: a seminal work from which Raymond Queneau, for instance, learned a great deal. More importantly, it is a precursor to the huge, essential work on outsider literature by André Blavier: Les Fous littéraires (1982; repr. with additions 2001).

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Nadar: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #8

Libellés :

Nadar,

Photography

Link to my earlier post on Père-Lachaise:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Anna de Noailles: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #7

Libellés :

French Literature,

Noailles (Anna de)

'SÉPULTURE DU PRINCE DE VALACHIE

GEORGES D. BIBESCO ET DE LA PRINCESSE BIBESCO'

Poet and novelist of Romanian extraction, Anna de Noailles was born Princesse Bibesco Bassaraba de Brancovan.

Inside the chapel, the plaque to Anna de Noailles.

'ANNA DE BRANCOVAN

COMTESSE

DE

NOAILLES

1933'

And at 22 boulevard de la Tour Maubourg in the 7th arrondissement:

'ICI EST NÉE

ANNA DE BRANCOVAN

COMTESSE DE NOAILLES

LE 15 NOVEMBRE

1876'

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Jean-François Champollion: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #6

Libellés :

Champollion (Jean-François),

French Literature

'ICI REPOSE

JEAN-FRANÇOIS CHAMPOLLION

NÉ À FIGEAC DEPT. DU LOT

LE 23 DÉCEMBRE 1790

DÉCÉDÉ À PARIS

LE 4 MARS 1832'

Jean-François Champollion was a prominent Egyptologist who wrote a large number of books on Egypt, particularly on its ancient hieroglyphics. There is a Musée Champollion in Figeac.

Link to my earlier post on Père-Lachaise:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Auguste Comte: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #5

Libellés :

Comte (Auguste),

French Literature,

Vaux (Clotilde de)

'L'AMOUR POUR PRINCIPE ET L'ORDRE POUR BASE

LE PROGRÈS POUR BUT

AUGUSTE COMTE

ET

SES TROIS ANGES'

'AUGUSTE COMTE

FONDATEUR DE LA RELIGION DE L'HUMANITÉ

1798–1857

COURS DE PHILOSOPHIE POSITIVE 1830–1842

LA POLITIQUE POSITIVE 1848–1854

LA SYNTHÈSE POSITIVE 1856'

'A

CLOTILDE

DE VAUX

sa mere

spirituelle

L'EGLISE

POSITIVISTE

DU BRÉSIL'

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Georges Rodenbach: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #4

Libellés :

Belgian Literature,

Rodenbach (Georges)

The tomb of the Belgian symbolist poet and novelist Georges Rodenbach (1855–98), one of the most striking in Père-Lachaise. He was from an aristocratic family of German origin, and a great-uncle established the Rodenbach brewery, which is still extant.

Link to my earlier post on Père-Lachaise:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Raymond Roussel: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #3

Libellés :

French Literature,

Roussel (Raymond)

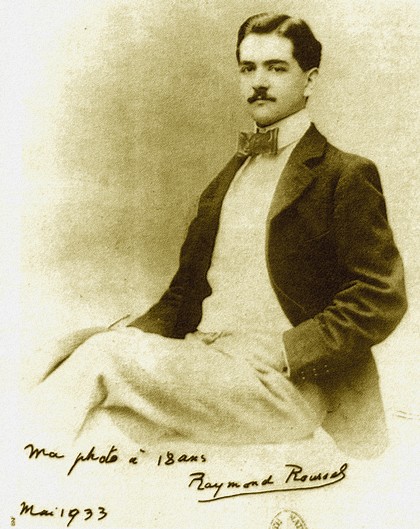

'RAYMOND

ROUSSEL

1877 – 1933'

Raymond Roussel's novels and plays were unsuccessful in his lifetime and he died of a massive overdose of barbiturates in Palermo. Only later would he be seen as a precursor, indeed a kind of godfather, of Oulipo.

And his influence continues. I've just noticed that Iain Sinclair mentions the novel The Vorrh by B. Catling as his most significant read of 2013 (TLS 5774, 29 November 2013). The name of this trilogy comes from Roussel's imaginary forest in Impressions d'Afrique (1910), a novel whose second part Roussel said must be read before the first part, as the first part came chronologically after the second.

Below is a link to one of Roussel's most famous novels:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Raymond Roussel: Locus Solus

Link to my earlier post on Père-Lachaise:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Jean-Pierre Martinet: Jérôme (L'Enfance de Jérôme Bauche) (1978; repr. with slight amplification 2008)

Libellés :

French Literature,

Martinet (Jean-Pierre)

This is not so much a novel as an experience you'll never forget. Jean-Pierre Martinet's Jérôme (L'Enfance de Jérôme Bauche) isn't just a major landmark in French literature but a major landmark in literature tout court. And yet it remains not only virtually unknown in the non-Francophone world, but hardly known even within the Francophone world itself.

Most of all, this is a huge outsider rant. In order to survive the first pages of this book, let alone to finish it, the reader must have a very strong constitution: virtually all human (and even animal) contact is seen as a kind of poison, and can perhaps only be relieved by murder or suicide. Ironically though, through all this comes a kind of jet black view of life that occasionally almost comes across as comedy.

Medieval too is the hellish underworld of the passage Nastenka, especially in the labyrinthine, multi-floored pissotières where homosexual buggery and broute-minou are on semi-public display, although an end is brought to his sex-crazed activities there when Lisa – her hair stiff with Bauche's sperm – hangs herself. Tongue in cheek, Eibel compares the maze-like geography of Nastenka to Châtelet's underground network (and I know what he means).

In a neat symmetry, mamame (Bauche's mother) dies of natural causes after Bauche has killed Cloret and nailed his feet to the floor to stop him from swaying onto the dinner table, and the taxi driver at the end has a heart attack after Bauche kills Paulina. Or maybe it's not Paulina at all, but anyway who cares – let's just bundle her into the taxi driver's cab that Bauche can't really drive and take her back to the other stiffs – although this only happens in the added chapters, not in the first edition.

So far so Oulipian, but then the language gets worse, and non-existent words appear that can't even be graced with the expression 'neologism', as neologisms usually have a logical rather than a meaningless (or let's call it insane) purpose: 'les nougris, les encervas, les freunisses', and a string of (imaginary) men Jérôme imagines Polly's had sex with. He's so crazy he'll strangle your pet cat in seconds if it passes his fancy that it looks like Polly.

But most of all, Jérôme reminds me of Charles Perry's only novel Portrait of a Young Man Drowning, with its schizophrenic other: just who is Solange? A female Jérôme clearly, but one who metamorphoses, one who seems reasoning, conscience-like at times, but cold, utterly brutal at others, and more disturbingly, one who is known by mamame, Cloret, and the shopkeeper Madame Parnot: is that all part of Jérôme's psychosis? Just how far does the narratorial unreliability go?

Biographical note: Jean-Pierre Martinet (1944–93) was born in Libourne. His father died when Jean-Pierre was a child, leaving his widow to bring up three children: his brother was backward, his sister insane, but Jean-Pierre a brilliant scholar. He only ever loved one woman, but she couldn't stop drinking and the experience destroyed him. A financial failure both as a writer and a small-time businessman, Martinet drank himself to death and died before he reached fifty.

My other Martinet posts:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Jean-Pierre Martinet: L'Ombre des forêts

Jean-Pierre Martinet: Nuits bleues, calmes bières

Jean-Pierre Martinet: La Somnolence

Jean-Pierre Martinet: La grande vie | The High Life

Jean-Pierre Martinet: Ceux qui n'en mènent pas large

Capharnaüm 2: Jean-Pierre Martinet sans illusions...

27 November 2013

Oscar Wilde (update): Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #2

Libellés :

Wilde (Oscar)

Since I was last here in 2011 Oscar Wilde's monument has been scrubbed clean of all the lipstick, loving comments and a few insults. I feel a certain ambivalence towards the clean-up, though.

Link to my earlier post on Père-Lachaise:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

Henri Barbusse: Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise #1

Libellés :

Barbusse (Henri),

French Literature

The most noted novel by Henri Barbusse (1873-1935) is the autobiographical Le Feu (1916), for which he won the Prix Goncourt, which was translated into English as Under Fire, and which tells of the time he spent on the front line of the trenches from December 1914 to 1916: he volunteered at 41 in spite of weak health, and in spite of previous pacifist declarations. Le Feu is considered as a very

significant work of war literature.

Link to my earlier post on Père-Lachaise:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise / Père Lachaise Cemetery

26 November 2013

Alain Mabanckou: Mémoires de porc-épic | Memoirs of a Porcupine (2006)

Libellés :

Congolese Literature,

French Literature,

Mabanckou (Alain)

A few reviews have remarked that Alain Mabanckou's Mémoires de porc-épic – translated as Memoirs of a Porcupine, although I prefer 'Porcupine Memoirs' – only contains one sentence, but it doesn't even have that: there isn't a single full stop in the whole 221-page novel, and the only capitalisation used is with proper nouns. But this doesn't make it what I would call an 'experimental' novel. It has six titled divisions, and many other divisions within those divisions: it just doesn't use sentences, preferring often long, comma-strewn passages.

The book is heavily influenced by African stories and legends, the principal one being the concept of human beings having an animal double. It's also influenced by writers from the Americas, and García Marquez's Macondo is mentioned, and there's also a passing reference to Edgar Allan Poe, although the Uruguayan writer Horacio Quiroga is dwelt on a little more.

But to return to doubles, the central (human) character is Kibandi, whose male ancestors have had animal doubles since way back. Kibandi's father initiates him, making him take the magic potion mavamvunbi, leading him to a porcupine double – although this is a double that performs bad as opposed to good things.

We only learn very near the end that Kibandi called the porcupine Ngoumba – we aren't told this before because 'Ngoumba' means 'porcupine', and the porcupine thinks he's rather more than just a porcupine, which he certainly is, but as we have no other name how else can we refer to him?

Ngoumba is the narrator, and as he has no friends to talk to at the end of the novel he addresses the story to the baobab tree in which he lives. And his story is very funny in spite of its black content, as it is partly a satire on human – especially white human – folly. Ngoumba may be a bad double, but he's pretty cultured – he reads, for instance, although he doesn't think much of the Bible. He even has a conscience, and although he is directed to kill people (acts which he's more or less obliged to fulfil as Kibandi's double) he's by no means always happy to do so.

Amédée, for instance (and unless I'm wildly out this surely calls to mind Ionesco's play?), is a pretentious asshole who may be highly learned but he wants everyone to know it, especially all the young girls who fall at his feet, and as he has nothing but insults for Kibandi he has to be killed. Interestingly (and this brings us back to Horacio Quiroga), Amédée has unwittingly spoken of his own downfall: with a group of young virgins at his feet hanging on to his every word but not hanging onto their virginity for long if Amédée can help it, he speaks of a short story by the Uruguayan writer.

This (although the title isn't mentioned) is Quiroga's 'El almohadón de plumas' ('The Feather Pillow') from his collection Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (1917) (Stories of Love, Madness and Death), which concerns the death of Alicia, who has had the blood sucked out of her temples for several days by a small monster living in her pillow: the porcupine kills more rapidly than this, by injecting his quills into the temple or base of the skull, although the result is the same (albeit less visible as he licks off the blood and waits a few seconds for the mark to disappear).

The porcupine doesn't at all like killing the baby of a dull-witted drunkard Kibandi has a grudge against because the man owes him money and insults him, and the killings increasingly lose any justification, until the porcupine fears – after 99 murders – that the next will be the last and be a disaster. By avoiding it, it doesn't happen, although the terrible twins Koty and Koté kill Kibandi, and yet the porcupine lives on after the death of his double, talking all the while to the baobab tree – maybe he's reprieved, can settle down and have kids. The reader hopes so.

Humans lose out in this book, but readers (in spite of all those, er, white lies) don't. This is entrancing, gripping, and although it may sound a little gruesome the violence is on a cartoon level: think of Astérix. Most of all this is a very original – and human – read.

My other posts on Alain Mabanckou:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Alain Mabanckou: Verre Cassé | Broken Glass

Alain Mabanckou: Lettre à Jimmy | Letter to Jimmy

Alain Mabanckou: Black Bazar | Black Bazaar

25 November 2013

Pierre Loti: Pêcheur d'Islande (1886)

Libellés :

French Literature,

Iceland,

Loti (Pierre)

There is no indication in the first paragraph of Pierre Loti's Pêcheur d'Islande (translated as An Iceland Fisherman) that the opening drinking scene takes place on a boat, although there is a suggestion of this in the evocative phrase of the room being 'tapered at one end like the inside of a huge gutted seagull' ('effil[é] par un bout, comme l'intérieur d'une grande mouette vidée'). Unfortunately the book doesn't continue with the same opening promise, but it's still worth a read.

Pêcheur d'Islande is largely set in Brittany in late nineteenth century Paimpol, where the lives of the people are essentially circumscribed by the men who work in the fishing industry, taking the boat every year from the Breton town to fish cod off the coast of Iceland from the end of February to the end of August. Austerity is the norm.

And death is also common, recorded on the tombstones in the town cemetery and those in the small cemetery in Iceland. The huge, handsome protagonist Jean (known as Yann here) is in his late twenties and is a close friend of Sylvestre, a mere innocent (Loti mentions his virginity and his shyness a few times) and in his late teens he is sent to China for his military service, is seriously wounded, and only makes the return journey as far as Singapore. His death devastates his grandmother Yvonne.

Living with Yvonne is the other main character in this book, which is more a sentimental love story than a book of gritty realism: Gaud comes from a wealthy family, her father having made a fortune in the fishing industry, but she isn't inerested in money and loves Yann with an unquenchable passion, although he doesn't respond to her obvious love. Until, that is, her father gambles all the money away and she becomes far poorer than Yann himself. It's then that Yann reciprocates the love, they enjoy six days of married bliss, and then Yann, like so many other men, gets killed on the return journey from Iceland.

The book is thick with sentimentality, and it's perhaps not surprising that this is Loti's most popular book, although there are many redeeming features here. If only Loti hadn't made Yann and Gaud so perfect: there are a few very minor phrases about Yann getting his wild oats, and he very rarely gets drunk (doesn't even touch a drop on his wedding day); but Gaud? no, I can't see a single blemish – this is just not realistic.

The link to my other Loti post is below:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Pierre Loti, Rochefort, and Saint-Pierre-d'Oléron

Pêcheur d'Islande is largely set in Brittany in late nineteenth century Paimpol, where the lives of the people are essentially circumscribed by the men who work in the fishing industry, taking the boat every year from the Breton town to fish cod off the coast of Iceland from the end of February to the end of August. Austerity is the norm.

And death is also common, recorded on the tombstones in the town cemetery and those in the small cemetery in Iceland. The huge, handsome protagonist Jean (known as Yann here) is in his late twenties and is a close friend of Sylvestre, a mere innocent (Loti mentions his virginity and his shyness a few times) and in his late teens he is sent to China for his military service, is seriously wounded, and only makes the return journey as far as Singapore. His death devastates his grandmother Yvonne.

Living with Yvonne is the other main character in this book, which is more a sentimental love story than a book of gritty realism: Gaud comes from a wealthy family, her father having made a fortune in the fishing industry, but she isn't inerested in money and loves Yann with an unquenchable passion, although he doesn't respond to her obvious love. Until, that is, her father gambles all the money away and she becomes far poorer than Yann himself. It's then that Yann reciprocates the love, they enjoy six days of married bliss, and then Yann, like so many other men, gets killed on the return journey from Iceland.

The book is thick with sentimentality, and it's perhaps not surprising that this is Loti's most popular book, although there are many redeeming features here. If only Loti hadn't made Yann and Gaud so perfect: there are a few very minor phrases about Yann getting his wild oats, and he very rarely gets drunk (doesn't even touch a drop on his wedding day); but Gaud? no, I can't see a single blemish – this is just not realistic.

The link to my other Loti post is below:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Pierre Loti, Rochefort, and Saint-Pierre-d'Oléron

22 November 2013

Oscar Milosz in Fontainebleau, Seine-et-Marne (77), France

Libellés :

Fontainebleau,

French Literature,

Milosz (Oscar),

Seine-et-Marne (77)

'OSCAR VLADISLAS DE L. MILOSZ

(1877–1939)

(1877–1939)

Ecrivain Français, poète, diplomate, Lituanien.

amis des oiseaux, fit de longs séjours à

l'Hôtel de l'Aigle Noir de 1930 à 1939.

amis des oiseaux, fit de longs séjours à

l'Hôtel de l'Aigle Noir de 1930 à 1939.

–––––––––––––––––––––

OSCAR VLADISLAS DE L. MILOSZ

(1877–1939)

French writer, poet, Lithuanian diplomat

and bird lover, enjoyed long stays at the

Hotel de l'Aigle Noir from 1930 to 1939.'

and bird lover, enjoyed long stays at the

Hotel de l'Aigle Noir from 1930 to 1939.'

'DANS CETTE MAISON MOURUT

LE 2 MARS 1939

LE POÈTE FRANÇAIS

D'ORIGINE LITHUANIENNE

O. V .DE L. MILOSZ NÉ EN 1877'

LE 2 MARS 1939

LE POÈTE FRANÇAIS

D'ORIGINE LITHUANIENNE

O. V .DE L. MILOSZ NÉ EN 1877'

Milosz moved into his new home on 1 February 1939, and died just

four weeks later. He is buried in the cemetery at Fontainebleau.

'O.V.de L. MILOSZ

Poète et Métaphysicien

Premier Représentant

de la Lithuanie

en France

...nous entrons dans

la seconde innocence,

dans la joie méritée,

reconquise, consciente.'

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)