Diane Kurys dedicated her first feature film, Diabolo Menthe (1977), to her sister, adding that she still hasn't returned the orange pullover she lent her. As dedications go, this may be slightly unusual, although on the surface at least it's perhaps by no means as cryptic as some. But the interesting thing here is that Kurys's films often involve the family, and we know that Kurys has a love-hate relationship with her sister.

À la folie may generally be considered less autobiographical than others of her films for a number of reasons, although two sisters are present, as well as children (initially). I certainly don't intend to draw any analogies between autobiography and fiction here, although everyone writes from experience, sometimes second-hand (through books or stories told, etc). The title of the film obviously relates to a common expression. What is the playful answer to the statement 'Je t'aime'? 'Un peu, beaucoup, à la folie, pas du tout ?' For all the three main characters, all of these answers can be applied at least once, often more, maybe on each of these occasions.

À la folie not only received negative reviews, but was generally panned by almost the whole press, and even to find any non-professional review is very difficult. Obviously it's normal to love or hate a work, but this one seems to have been greeted with general incomprehension. I'm feeling my way around Diane Kurys's films, and this is only the second I've viewed after La Baule-les-Pins, which – in spite of a the occasional quirkiness – seems (initially at least) far less complex than this film which came out four years later. Not only more complex, but far weirder.

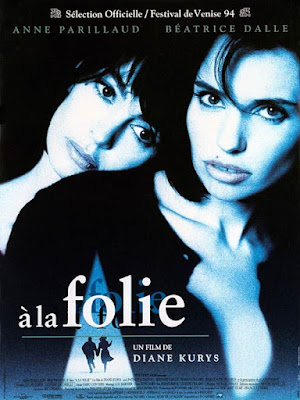

First we have two female actors – the sisters Anne Parillaud (as Alice) and Béatrice Dalle (as Elsa), both of whom have appeared in leading roles in what was known as the 'cinéma du look', Luc Besson's Nikita (1990) and Jean-Jacques Beineix's 37°2 le matin (1986) respectively; then Elsa's husband Douglas (Alain Chabat), by whom she has two children, and who as an actor was more noted for comedies; and then there's the far less known Patrick Aurignac (here as Franck), who had (in real life) spent many years in prison, and directed just one film: Mémoires d'un con, made just two years after À la folie and who shot himself dead in the same year as his badly-received film was released.

Elsa leaves her adulterous husband and her two children – about whom she seems to mention no more - on the pretext of buying milk, and yet she takes the coach for Paris in her slippers and Douglas's raincoat to see Alice, the sister she's not seen for two years, and who doesn't seem too interested in their parents. Alice is a budding artist who tells her agent Sanders (Bernard Verley) that she doesn't feel professionally ready for New York and the cultural hike; and then her boyfriend Franck moves in with her, fridge and all, without prior warning; and then the unwanted cherry on the unwanted cake: Elsa turns up suddenly on her doorstep (or near, but that's another point), having left her family.

What existential horrors are there for Alice alone? She's professionally far from certain that she wants NYC at the moment, her lover (an amateur boxer) has dumped himself on her, as has her not-too-familiar sister. What ensues is an odd ménage à trois, with conflicting but constantly changing loyalties, hell seen as other people, minor violence (or threat) being the norm.

But what are we to make of this hotchpotch? Things we don't expect to happen in fact happen: Franck, at the risk to his life, goes on top of the high story of the apartment to rescue the life of a pigeon stuck to the pantry grill, and which he feeds in the apartment; how much, if anything, that we see is in fact real? Is Alice's (symbolic?) enchainment to the radiator really an excuse for Elsa to have sex with Franck and not an attempt to restrain her from killing herself?

All three people here are trapped within their own minds, but also within those of the other two, but there is humour here. Initially, Franck is for Elsa moving, asking her how long she's staying, Alice says as long as she likes, and Franck walks off, ironically saying 'On va rigoler !" ('We're gonna have a blast!'). The most humorous moment (in its surreality) is when Douglas comes looking for Elsa, who is hiding under Alice's bed, but Douglas sees this, shoves his face down from the bed to talk to her and then joins his wife under the bed and attempts a conversation while they're on their bellies on the floor. Franck asks while he's down there if he wants a beer but he says whiskey; Alice tells Franck to drive Thomas back to the train station (La Gare de Lyon). But what of the crude drawing of the dog Elsa had originally slid under Alice's door? It's a dead one with a cross on it. When they lived at home, their father said that Alice had 'du chien', which could mean she was cute? What of this and its relation to a dead dog?

Well, in the final scenes Alice is about to break through as an artist, is now in New York with a new boyfriend, so all's OK? Not quite, as Alice gets another dead dog drawing shoved under her door. Real, or just meaning that you can't go home again as you never left? If shit sticks, that includes dogshit, and you can never be free? Just thinking aloud as it were, but I adored this film.

No comments:

Post a Comment