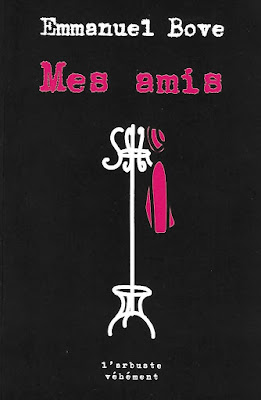

This is the cult writer Emmanuel Bove's first novel, encouraged by Colette. Mes amis is something of an ironic title, as the main character, the first person narrator Victor Bâton, who lives on a small pension following World War I, has no friends. He's not smelly or mad or anything, although he lives in a crappy appartment block whose architect didn't bother to engrave his name, where there's no bathroom, just a communal sink with a curtain where people wash themselves.

Victor is a very aware person, no doubt too aware, too sensitive, and occasional sex sessions with the barmaid Lucie Dunois, from the local café, don't quite fulfill him. But then his short attempt to find a friend in Henri Billard doesn't please him either: it seems to be more Billard's live-in girlfriend who's the problem rather than Billard himself. The fifty francs that Victor's lent the obviously richer Henri, even though Victor only gets three hundred every three months? Forget it, it's not worth thinking about.

We could continue with Neveu, the poverty-stricken sailor who wants to kill himself along with Henri, but Henri won't find friendship in a suicide pact, in fact he won't find a friend. It's a cruel life.

Victor is a very aware person, no doubt too aware, too sensitive, and occasional sex sessions with the barmaid Lucie Dunois, from the local café, don't quite fulfill him. But then his short attempt to find a friend in Henri Billard doesn't please him either: it seems to be more Billard's live-in girlfriend who's the problem rather than Billard himself. The fifty francs that Victor's lent the obviously richer Henri, even though Victor only gets three hundred every three months? Forget it, it's not worth thinking about.

We could continue with Neveu, the poverty-stricken sailor who wants to kill himself along with Henri, but Henri won't find friendship in a suicide pact, in fact he won't find a friend. It's a cruel life.

My other posts on Emmanuel Bove:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

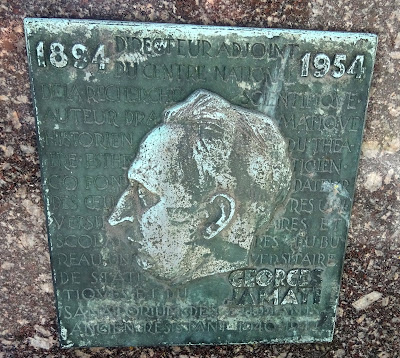

Montparnasse Cemetery / Cimetière du Montparnasse

Emmanuel Bove: Le Piège (1945)

Emmanuel Bove: Cœurs et visages