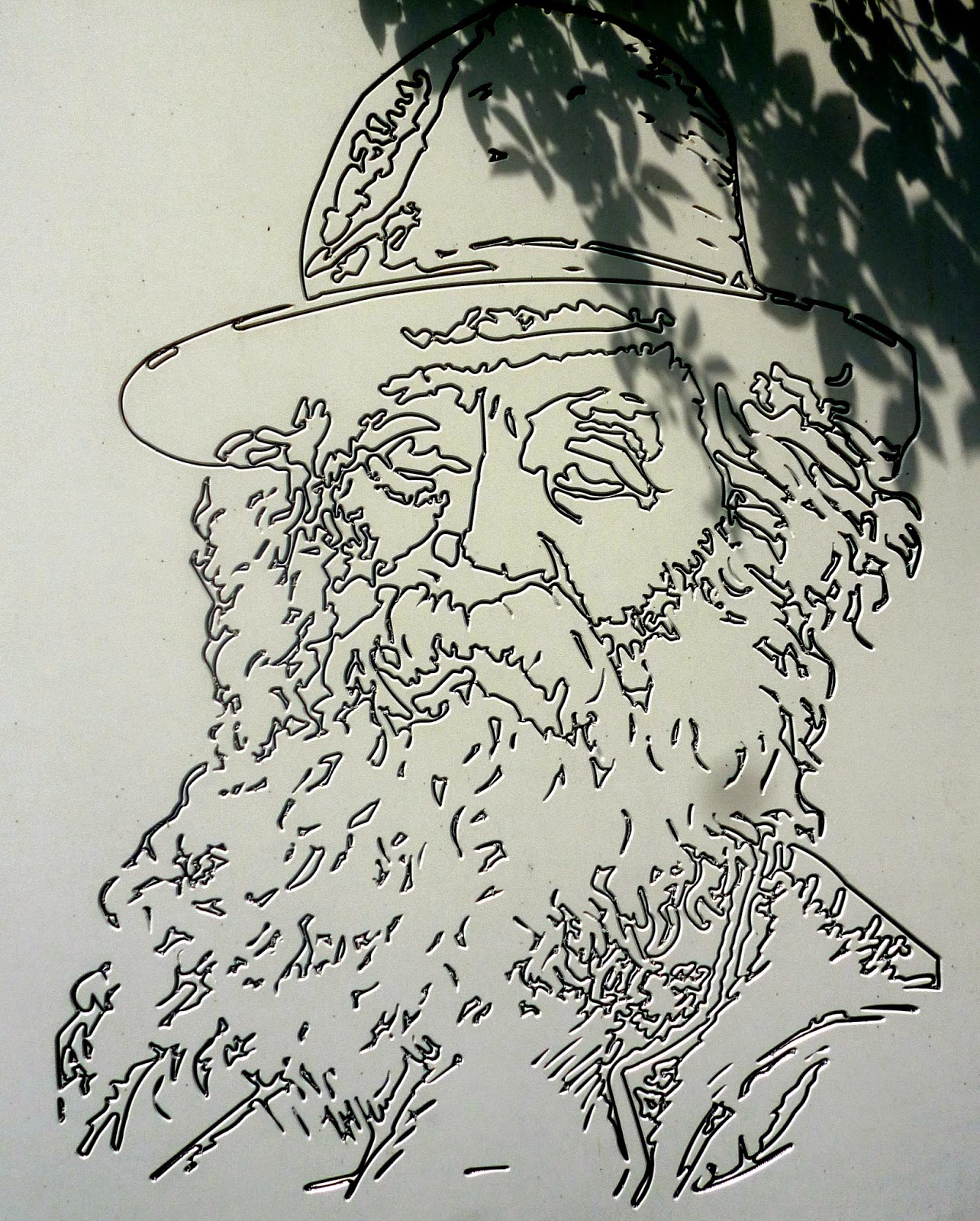

Louis Hémon's Maria Chapdelaine sold a few million copies and three movies were produced based on it. And yet Hémon (1880–1913) is scarcely remembered anywhere apart from Canada, where he was killed by a train at the age of thirty-two.

Last year was the 100th anniversary of the death of the author of Maria Chapdelaine, which Le Nouvel Observateur marked by this article, which underlines Hémon's present-day obscurity in France, the country of his birth. The novel was first published in serial form in Paris and as a book in Montréal in 1916.

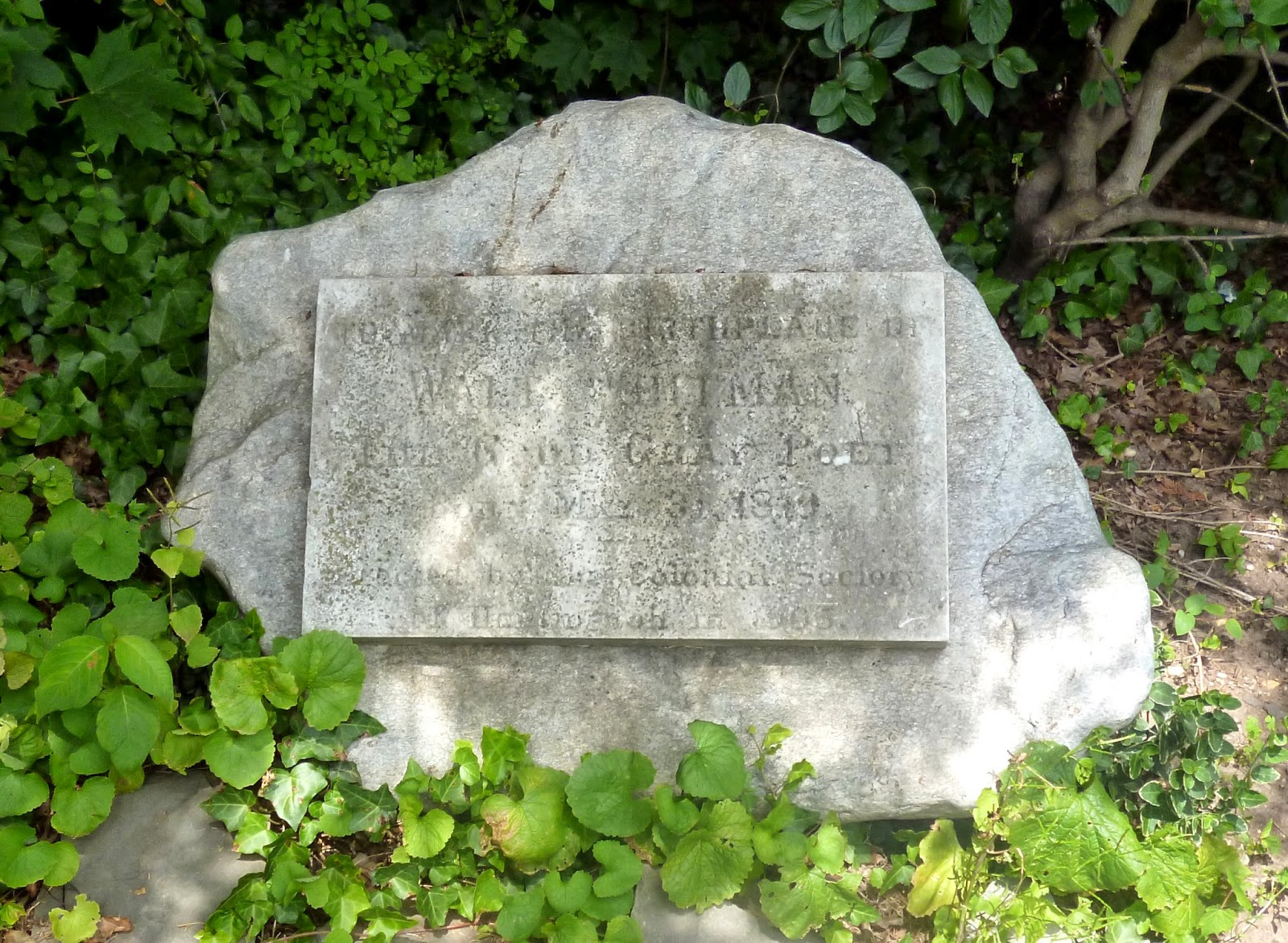

Maria Chapdelaine is set in Québec in the Saguenay – Lac-Saint-Jean area, with specific mention of Péribonka, where there is a Musée Louis Hémon, which incorporates the house of Samuel Bédard where Hémon lodged shortly before his death.

Maria lives with her parents in an isolated house, her father being a peasant farmer-cum-land-clearer. Each year is dictated by the whim of the weather, although winters always last several months and the snow is deep, and a long tough winter means scanty resources during the short summer. Prayer is a way of life, resignation almost an inherited disease.

Against this bleak backcloth a love story is central, and three men vie for Maria's hand: François Paradis, a woodcutter who has sold the family property to live an itinerant (but relatedly free) existence; Lorenzo Surprenant, who has moved to the US and to the bright lights of the cities where there is much more money; and Eutrope Gagnon, who lives closest to the family and whose life is much the same hardscrabble existence and whose prosaic, repetitive conversation mirrors that of her family's.

François and Maria are in love: he has made it clear to her that he is saving as much money as he can, and he is distancing himself from the masculinist environment he works in by not drinking or using 'profane' language. He says he will return to her the following spring, and she agrees to wait for him. And wait she does, chained to her rosary until she learns that François has made an attempt to see her for the New Year, but frozen to death in the process.

Maria is devastated but not broken and knows that she has to continue life through the grief. Her sense of hope for the future tells her that she should be with Lorenzo, but in the end her conservatism makes her choose Eutrope to stick to the land she 'belongs' to, stick with the language she has grown up with:

'A travers les heures de la nuit Maria resta immobile, les mains croisées dans son giron, patiente et sans amertume, mais songeant avec un peu de regret pathétique aux merveilles lointaines qu'elle ne connaîtrait jamais et aussi aux souvenirs tristes du pays où il lui était commandé de vivre'.

'Through the hours of the night Maria remained motionless, her hands in her lap, patient and without bitterness, but thinking with a little pitiful regret about the distant wonders that she would never know, and also of the sorrowful memories of the country in which she was ordered to live'. (My translation.)

Last year was the 100th anniversary of the death of the author of Maria Chapdelaine, which Le Nouvel Observateur marked by this article, which underlines Hémon's present-day obscurity in France, the country of his birth. The novel was first published in serial form in Paris and as a book in Montréal in 1916.

Maria Chapdelaine is set in Québec in the Saguenay – Lac-Saint-Jean area, with specific mention of Péribonka, where there is a Musée Louis Hémon, which incorporates the house of Samuel Bédard where Hémon lodged shortly before his death.

Maria lives with her parents in an isolated house, her father being a peasant farmer-cum-land-clearer. Each year is dictated by the whim of the weather, although winters always last several months and the snow is deep, and a long tough winter means scanty resources during the short summer. Prayer is a way of life, resignation almost an inherited disease.

Against this bleak backcloth a love story is central, and three men vie for Maria's hand: François Paradis, a woodcutter who has sold the family property to live an itinerant (but relatedly free) existence; Lorenzo Surprenant, who has moved to the US and to the bright lights of the cities where there is much more money; and Eutrope Gagnon, who lives closest to the family and whose life is much the same hardscrabble existence and whose prosaic, repetitive conversation mirrors that of her family's.

François and Maria are in love: he has made it clear to her that he is saving as much money as he can, and he is distancing himself from the masculinist environment he works in by not drinking or using 'profane' language. He says he will return to her the following spring, and she agrees to wait for him. And wait she does, chained to her rosary until she learns that François has made an attempt to see her for the New Year, but frozen to death in the process.

Maria is devastated but not broken and knows that she has to continue life through the grief. Her sense of hope for the future tells her that she should be with Lorenzo, but in the end her conservatism makes her choose Eutrope to stick to the land she 'belongs' to, stick with the language she has grown up with:

'A travers les heures de la nuit Maria resta immobile, les mains croisées dans son giron, patiente et sans amertume, mais songeant avec un peu de regret pathétique aux merveilles lointaines qu'elle ne connaîtrait jamais et aussi aux souvenirs tristes du pays où il lui était commandé de vivre'.

'Through the hours of the night Maria remained motionless, her hands in her lap, patient and without bitterness, but thinking with a little pitiful regret about the distant wonders that she would never know, and also of the sorrowful memories of the country in which she was ordered to live'. (My translation.)

.jpg)