Three interpretation panels give background details of the farm. One, entitled 'The Farm', states: 'Between 1931 and 1939, Bernard McHugh Cline, M.D. (Flannery O'Connor's uncle) purchased this farm, which had once been the core of a 19th century plantation. With the help of employees and family members like Dr. Cline's brother-in-law, Frank Florencourt, Andalusia became a fully functional farm with electricity and other amenities. As the farm operation eventually expanded other improvements were made, such as the distribution of well water around the complex in underground copper pipes. When Dr. Cline died in 1947, the property went to Flannery's mother, Regina Cline O'Connor, and another uncle, Louis Cline.'

Three interpretation panels give background details of the farm. One, entitled 'The Farm', states: 'Between 1931 and 1939, Bernard McHugh Cline, M.D. (Flannery O'Connor's uncle) purchased this farm, which had once been the core of a 19th century plantation. With the help of employees and family members like Dr. Cline's brother-in-law, Frank Florencourt, Andalusia became a fully functional farm with electricity and other amenities. As the farm operation eventually expanded other improvements were made, such as the distribution of well water around the complex in underground copper pipes. When Dr. Cline died in 1947, the property went to Flannery's mother, Regina Cline O'Connor, and another uncle, Louis Cline.'

The front porch.

The front porch.

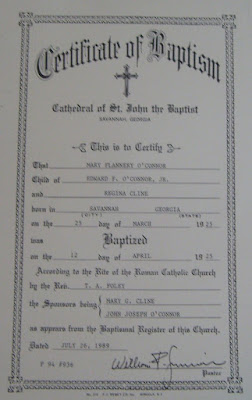

Photos of Flannery O'Connor's father, Edward Francis O'Connor, Jr, and her uncle, Dr Bernard McHugh Cline.

Photos of Flannery O'Connor's father, Edward Francis O'Connor, Jr, and her uncle, Dr Bernard McHugh Cline.

Flannery O'Connor's bedrooom, with the familiar crutches.

Flannery O'Connor's bedrooom, with the familiar crutches.

The dining room.

The dining room.

The kitchen.

The kitchen.

The interpretation panel entitled 'The Property' states: 'On the National Register of Historic Places since 1980, Andalusia is a 544-acre farm composed of gently rolling hills divided into a farm complex, hayfields, pasture and man-made and natural ponds, and forests. Tobler Creek intersects the property, entering near the west corner and meandering down to exit at the southeast boundary. The farm complex comprises roughly twenty-one acres of the property and also includes a livestock pond at the bottom of the hill south of the Main House. During her productive years as a writer, Flannery O'Connor lived at Andalusia with her mother, Regina Cline O'Connor, from 1951 until her death in 1964.'

The barn.

The barn.

The third panel is entitled 'A Literary Landscape' and reads: 'The argicultural setting of Andalusia, with its laborers, buildings, equipment, and animals, figures prominently in Flannery O'Connor's work. Southern literature places great emphasis on a sense of place, where the landscape becomes a major force in the shaping of the action. Andalusia provided for O'Connor not only a place to live and write, but also a functional landscape in which to set her fiction. While living here, O'Connor completed to novels, Wise Blood (1952) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960), and two short story collections, A Good Man Is hard to Find (1955) and Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965).'

Flannery O'Connor's grave in Milledgeville cemetery.

Flannery O'Connor's grave in Milledgeville cemetery.

Conrad Aiken (1989–73) was a modernist, a friend of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and the mentor of Malcolm Lowry. Although he was born and died in Savannah, Georgia, he was swift to disclaim any literary affinity with Southern writers: in an interview with Robert Hunter Wilbur published in an issue of The Paris Review of 1968, he said:

Conrad Aiken (1989–73) was a modernist, a friend of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and the mentor of Malcolm Lowry. Although he was born and died in Savannah, Georgia, he was swift to disclaim any literary affinity with Southern writers: in an interview with Robert Hunter Wilbur published in an issue of The Paris Review of 1968, he said:

'I’m not in the least Southern; I’m entirely New England. […] I was never connected with any of the Southern writers.'

From the age of 11, he was brought up by an aunt in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and educated in the same state, finishing his education at Harvard.

Nevertheless, he returned to Savannah every summer, although he describes this as ‘Shock treatment’: ‘The milieu [was] so wholly different, and the social customs, and the mere transplantation; as well as having to change one’s accent twice a year – all this quite apart from the astonishing change of landscape. From swamps and Spanish moss to New England rocks.’

It is pouring, it feels like flooding underfoot, but there's a grave to be found, and I inch the car through Bonaventure Cemetery in search of the Aikens' plot. I leave the car – and the dry Penny – in a small parking patch and half run to the site. The idea of the bench-grave, it is said, is that Aiken wanted people to sit down on it and enjoy a glass of Madeira, although, of course, this would now almost certainly be illegal.

It is pouring, it feels like flooding underfoot, but there's a grave to be found, and I inch the car through Bonaventure Cemetery in search of the Aikens' plot. I leave the car – and the dry Penny – in a small parking patch and half run to the site. The idea of the bench-grave, it is said, is that Aiken wanted people to sit down on it and enjoy a glass of Madeira, although, of course, this would now almost certainly be illegal.

Aiken lived in fear of madness, and all his life he was traumatised by his discovery – at the age of 11 – of the bodies of his parents in their home in Savannah: his unstable father had killed his mother and then himself. On one occasion he was traveling to be psychoanalysed by Freud, although Eric Fromm discouraged him.

Aiken lived in fear of madness, and all his life he was traumatised by his discovery – at the age of 11 – of the bodies of his parents in their home in Savannah: his unstable father had killed his mother and then himself. On one occasion he was traveling to be psychoanalysed by Freud, although Eric Fromm discouraged him.

On returning to the car, Penny thinks it would be a good idea to get a few shots of the Johnny Mercer grave too, now we're here and (one of us at least) soaked to the skin already anyway. Yeah, good idea, do the crazy tourist thing, eh? Well, he was a writer too. So back I go, and, mirabile dictu, I meet a bunch of equally crazy, equally soaked, Americans taking photos of Mercer's grave, discussing his relation to others in the Mercer plot. I shoot back to the warmth of the car, grab a coffee at the nearest McDonalds, and it's foot down all the way to Macon 166 miles away. And the comfort of the next hotel.

On returning to the car, Penny thinks it would be a good idea to get a few shots of the Johnny Mercer grave too, now we're here and (one of us at least) soaked to the skin already anyway. Yeah, good idea, do the crazy tourist thing, eh? Well, he was a writer too. So back I go, and, mirabile dictu, I meet a bunch of equally crazy, equally soaked, Americans taking photos of Mercer's grave, discussing his relation to others in the Mercer plot. I shoot back to the warmth of the car, grab a coffee at the nearest McDonalds, and it's foot down all the way to Macon 166 miles away. And the comfort of the next hotel.

The Mercer–Williams House Museum in Bull Street, Savannah, is perhaps the most famous house in the town, so very little need be said of it, other than that it was also designed by John S. Norris, and that its fame now largely comes from John Berendt's novel Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994). This novel reconstructed the trials of antique dealer Jim Williams, the owner of the house at the time that he killed Danny Hansford in it, and who was eventually aquitted.

The Mercer–Williams House Museum in Bull Street, Savannah, is perhaps the most famous house in the town, so very little need be said of it, other than that it was also designed by John S. Norris, and that its fame now largely comes from John Berendt's novel Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994). This novel reconstructed the trials of antique dealer Jim Williams, the owner of the house at the time that he killed Danny Hansford in it, and who was eventually aquitted.

The Andrew Low House, designed by John S. Norris, stands in Lafayette Square, Savannah, Georgia, and is named after the wealthy British cotton broker who invited William Makepeace Thackeray to his house in 1853 and 1856. Thackeray greatly enjoyed the tranquil atmosphere of the town, and the free lodging.

The Andrew Low House, designed by John S. Norris, stands in Lafayette Square, Savannah, Georgia, and is named after the wealthy British cotton broker who invited William Makepeace Thackeray to his house in 1853 and 1856. Thackeray greatly enjoyed the tranquil atmosphere of the town, and the free lodging.

The Edgar Allan Poe Museum, 1914 West Main Street, Richmond, Virginia. Poe lived in perhaps nine houses in Richmond, but all have long since been demolished. The Old Stone House was standing in Poe's time, though, and Poe lived in Richmond for 13 of his 40 years.

The Edgar Allan Poe Museum, 1914 West Main Street, Richmond, Virginia. Poe lived in perhaps nine houses in Richmond, but all have long since been demolished. The Old Stone House was standing in Poe's time, though, and Poe lived in Richmond for 13 of his 40 years.

'The oldest house still standing in Richmond. Probably built 1737 by Joseph Ege. A gift in 1912 from Mr. and Mrs. Granville C. Valentine to the Assocation for the preservation of Virginia antiquities. Restored by Mr. and Mrs. Archer G. Jones. In 1924 placed in custody of the Edgar Allan Poe Shrine (now the Edgar Allan Poe Foundation, inc.'

'The oldest house still standing in Richmond. Probably built 1737 by Joseph Ege. A gift in 1912 from Mr. and Mrs. Granville C. Valentine to the Assocation for the preservation of Virginia antiquities. Restored by Mr. and Mrs. Archer G. Jones. In 1924 placed in custody of the Edgar Allan Poe Shrine (now the Edgar Allan Poe Foundation, inc.'

This bust of Poe stands in the Poe Shrine in the Enchanted Garden, and is a copy of one donated by the Bronx Historical Society: the Poe Cottage in the Bronx, of course, is the photo at the head of this blog.

This bust of Poe stands in the Poe Shrine in the Enchanted Garden, and is a copy of one donated by the Bronx Historical Society: the Poe Cottage in the Bronx, of course, is the photo at the head of this blog.

A plaque in the Enchanted Garden: 'In grateful memory. Richard Turner Arrington 1901–1960 President and faithful benefactor of the Edgar Allan Poe Museum "Gone proudly friended".'

A plaque in the Enchanted Garden: 'In grateful memory. Richard Turner Arrington 1901–1960 President and faithful benefactor of the Edgar Allan Poe Museum "Gone proudly friended".'

The Enchanted Garden seen from the Poe Shrine.

The Enchanted Garden seen from the Poe Shrine.

A view of the Enchanted Garden, facing the Poe Shrine. The garden was landscaped in 1921, and modeled after the description of the garden in Poe's poem 'To One in Paradise'. Bricks from the offices of the Southern Literary Messenger were used for the Poe Shrine and some of the garden. As 1909 marks the centenary of Poe's birth, the chairs are there for a series of events celebrating the occasion.

A view of the Enchanted Garden, facing the Poe Shrine. The garden was landscaped in 1921, and modeled after the description of the garden in Poe's poem 'To One in Paradise'. Bricks from the offices of the Southern Literary Messenger were used for the Poe Shrine and some of the garden. As 1909 marks the centenary of Poe's birth, the chairs are there for a series of events celebrating the occasion.

The Exhibits Building was acquired in 1929. Once the tea room, this two-story building now houses changing exhibits.

The Exhibits Building was acquired in 1929. Once the tea room, this two-story building now houses changing exhibits.

Engulfed by vegetation so impossible to photo adequately, the Elizabeth Arnold Poe building, named after his mother, contains first editions of Poe's work donated by Dr John Robertson, a psychiatrist who wrote Poe: A Psychopathic Study. Unfortunately, photographing of the interior – even without flash – is not allowed.

The statue of Edgar Allan Poe in the grounds of the Capitol, Richmond.

The statue of Edgar Allan Poe in the grounds of the Capitol, Richmond.

Carl Sandburg (1878-1967) was born in Galesburg, Illinois, of Swedish immigrant parents and left school at 13 to help support his family. He left home six years later to drift around the country working on farms and railroads, which gave him a great insight into working-class America. He later went to college, failed to get a degree, but had been writing through college and in the early years of the 20th century Sandburg was writing against worker exploitation and child labor.

In 1908 Sandburg married Lilian Steichan, and continued to write as a journalist and to publish poetry. The Sandburg family, which now included three daughters, moved to a property on Lake Michigan, and by the mid-1930s Lilian had begun to raise goats, naming them Chikaming after the town they lived in.

By the early 1940s Sandburg was famous, and at the age of 67 he moved - with his family, which included two grandchildren from daughter Helga's failed marriage - to Flat Rock, North Carolina.

The Front Lake.

The Front Lake.

Connemara is a sizeable farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains, and Sandburg lived there for 22 years until his death. Lilian continued her goat business there. Christopher Memminger, who during the Civil War was Secretary of the Confederate Treasury, built the house in 1838, and the next owner - textile magnate Ellison Smyth - called it Connemara because of his Irish background.

Connemara is a sizeable farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains, and Sandburg lived there for 22 years until his death. Lilian continued her goat business there. Christopher Memminger, who during the Civil War was Secretary of the Confederate Treasury, built the house in 1838, and the next owner - textile magnate Ellison Smyth - called it Connemara because of his Irish background.

Sandburg's office. He published many more books while at Connemara, and earned a second Pulitzer prize.

Sandburg's office. He published many more books while at Connemara, and earned a second Pulitzer prize.

Sandburg brought 14,000 books with him from Michigan when he bought the property from Ellison Smyth.

Sandburg brought 14,000 books with him from Michigan when he bought the property from Ellison Smyth.

The dining room.

The dining room.

The kitchen.

The kitchen.

The laundry room.

The laundry room.

Lilian's goat farm.

Lilian's goat farm.

With a close-up of the goat barn.

With a close-up of the goat barn.

And a view of the production process.

And a view of the production process.

Finally, two of the goats in one of the fields.

Finally, two of the goats in one of the fields.

Paula Steichan's My Connemara: Carl Sandburg's Granddaughter Tells What It Was Like to Grow up Close to the Land on the Famous Poet's North Carolina Mountain Farm gives some interesting glimpses into life in Connemara with Carl Sandburg.

Paula Steichan's My Connemara: Carl Sandburg's Granddaughter Tells What It Was Like to Grow up Close to the Land on the Famous Poet's North Carolina Mountain Farm gives some interesting glimpses into life in Connemara with Carl Sandburg.

Three interpretation panels give background details of the farm. One, entitled 'The Farm', states: 'Between 1931 and 1939, Bernard McHugh Cline, M.D. (Flannery O'Connor's uncle) purchased this farm, which had once been the core of a 19th century plantation. With the help of employees and family members like Dr. Cline's brother-in-law, Frank Florencourt, Andalusia became a fully functional farm with electricity and other amenities. As the farm operation eventually expanded other improvements were made, such as the distribution of well water around the complex in underground copper pipes. When Dr. Cline died in 1947, the property went to Flannery's mother, Regina Cline O'Connor, and another uncle, Louis Cline.'

Three interpretation panels give background details of the farm. One, entitled 'The Farm', states: 'Between 1931 and 1939, Bernard McHugh Cline, M.D. (Flannery O'Connor's uncle) purchased this farm, which had once been the core of a 19th century plantation. With the help of employees and family members like Dr. Cline's brother-in-law, Frank Florencourt, Andalusia became a fully functional farm with electricity and other amenities. As the farm operation eventually expanded other improvements were made, such as the distribution of well water around the complex in underground copper pipes. When Dr. Cline died in 1947, the property went to Flannery's mother, Regina Cline O'Connor, and another uncle, Louis Cline.' The front porch.

The front porch. Photos of Flannery O'Connor's father, Edward Francis O'Connor, Jr, and her uncle, Dr Bernard McHugh Cline.

Photos of Flannery O'Connor's father, Edward Francis O'Connor, Jr, and her uncle, Dr Bernard McHugh Cline. Flannery O'Connor's bedrooom, with the familiar crutches.

Flannery O'Connor's bedrooom, with the familiar crutches. The dining room.

The dining room. The kitchen.

The kitchen. The barn.

The barn. Flannery O'Connor's grave in Milledgeville cemetery.

Flannery O'Connor's grave in Milledgeville cemetery.