31 August 2020

Éric Chevillard: Choir (2010)

Choir, literally meaning 'Falling' (possibly in a (mock-)religious sense), is almost undoubtedly one of Éric Chevillard's bleakest books, with suggestions of (waiting for) Godot, Endgame and a little Lautréamont.

The inhabitants of the island of the same name all want to leave the hell they're in: a place that can be freezing, where food (such as it is, and often they rely on root crops, animals they catch, or even eating themselves – at one time when people had died, or there's a suggestion of parents eating their young). The land is covered in guano or infertile sand, sometimes quicksand in which they're buried alive. Not only is the land itself hostile, but they're prey to savage animals or even themselves as there's frequent infighting.

This is not a timeless environment because planes often arrive there: forced to land for whatever reason, the planes crash, are forced by necessity to land on Choir, or are drawn to the island as if by some kind of magnetism – there's a suggestion of a kind of Bermuda triangle. Whatever the reason, any survivors are unable to make contact with any outside civilisation and must join with the others in fruitlessly wanting to leave. Inevitably, this seems (as in Beckett) to be a description of the human condition.

Contradictions abound, the hunters become the hunted, sleep is avoided for fear of dreaming of Choir only to wake up to the living nightmare, misfortunes are counted off as if prayers on a rosary, and sex is generally avoided because it can only result in producing more despairing life. And yet one game consists in causing the opponent as much harm as possible without killing him, as if misery must paradoxically be prolonged.

But there's hope of a kind. In the centre of the island is a statue to the one person who has succeeded in escaping from the island – Ilinuk, who built a machine from the wreckage of the planes: he is worshipped as a god, and the main essential thread in this story is the aged Yoakam's tales of his relationship with Ilinuk and of how he awaits his promised return, like a saviour coming back to free his people from their servitude. Or could he be rambling, is Ilinuk dead or did he in fact exist? Chevillard piles on the misery, emphasizing one of his obsessive themes: the impossibility of survival.

The inhabitants of the island of the same name all want to leave the hell they're in: a place that can be freezing, where food (such as it is, and often they rely on root crops, animals they catch, or even eating themselves – at one time when people had died, or there's a suggestion of parents eating their young). The land is covered in guano or infertile sand, sometimes quicksand in which they're buried alive. Not only is the land itself hostile, but they're prey to savage animals or even themselves as there's frequent infighting.

This is not a timeless environment because planes often arrive there: forced to land for whatever reason, the planes crash, are forced by necessity to land on Choir, or are drawn to the island as if by some kind of magnetism – there's a suggestion of a kind of Bermuda triangle. Whatever the reason, any survivors are unable to make contact with any outside civilisation and must join with the others in fruitlessly wanting to leave. Inevitably, this seems (as in Beckett) to be a description of the human condition.

Contradictions abound, the hunters become the hunted, sleep is avoided for fear of dreaming of Choir only to wake up to the living nightmare, misfortunes are counted off as if prayers on a rosary, and sex is generally avoided because it can only result in producing more despairing life. And yet one game consists in causing the opponent as much harm as possible without killing him, as if misery must paradoxically be prolonged.

But there's hope of a kind. In the centre of the island is a statue to the one person who has succeeded in escaping from the island – Ilinuk, who built a machine from the wreckage of the planes: he is worshipped as a god, and the main essential thread in this story is the aged Yoakam's tales of his relationship with Ilinuk and of how he awaits his promised return, like a saviour coming back to free his people from their servitude. Or could he be rambling, is Ilinuk dead or did he in fact exist? Chevillard piles on the misery, emphasizing one of his obsessive themes: the impossibility of survival.

30 August 2020

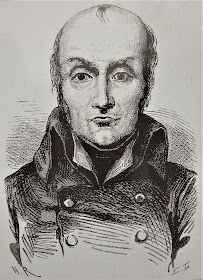

Alexis Piron in Dijon, (Côte-d'Or (21))

'ALEXIS PIRON

POÈTE SATIRIQUE

1689 - 1773'

Also in the Jardin de l'Arquebuse in Dijon is Piron's bust. He was a playwright as well as a poet and a man of undoubted brillance and quick wit, although his first published work, an erotic poem written about the age of twenty – Ode à Priape (1710) – was to dog him throughout his life and prevent him from being elected to the Académie française. His self-composed, self-denigrating epitaph is rather harsh:

'Ci-gît Piron

qui ne fut rien,

Pas même académicien'.

27 August 2020

Aloysius Bertrand in Dijon, (Côte-d'Or (21))

Louis Jacques Napoléon Bertrand, or Aloysius Bertrand (1807-41) was a poet, playwright and journalist considered as the inventor of the prose poem. He is most noted as the author of Gaspard de la nuit (1842). He spent much of his life in Dijon, although he died in Paris and is buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse. His bust in Le Jardin de l'Arquebuse in Dijon contains a quotation from Gaspard: 'J'étais un jour assis a l'écart dans le jardin de l'Arquebuse'.

Éric Chevillard: Monotobio (2020)

OK, Monotobio as opposed to 'Mon autobio', with four rounded sounds and no drag on the tongue. Éric Chevillard has spoken of himself before, in fact in all his books (although usually indirectly of course), particularly perhaps in Le Désordre azerty (2014). But this is the real thing, or as near as real to autobiography as probably Chevillard will get: almost everything in this book is about his life, although I'm well aware that there may be an unreliable narrator in place at times.

There's a catch of course, but then what do you expect from a Minuit writer, especially of Chevillard's nature? Chevillard hates narrative conventions, hates writing that follows on, so this is not the story of the novelist's life, or rather not a conventional story. Here we have memories, floods of them, apparently totally insignificant incidents such as (accidentally) scalding an earwig, drowning an ant, deliberately truncating a lizard's tail to watch the cut part wriggle for a few seconds but slowly grow back on the reptile again as a (surely misconceived?) lesson to his daughters; but then Chevillard, who bizarrely sees himself as a variety of vegetarian (is that a joke?), in spite of his obvious love of the animal kingdom, in spite of his sympathy for the exotic spider who briefly shares his room, loves eating animals. But I digress.

Monotobio is a book in which we learn by installments, in no obvious chronological order, of Chevillard's life as if through stream of consciousness or internal monologue, although of course there are many omissions he chooses to make, although you'll no doubt never know which. But you will learn of his marriage to Cécile, of his daughters Agathe (first) and then (around the same time of his father Bernard's death) of the birth of Suzie, his siblings and his friends. His parents have/had a holiday home on L'Île d'Yeu just off the Vendée coast, where the family go every summer, and here we learn of lot of the island.

We are told of course of many of Chevillard's books being published or in preparation, and it's in the cemetery of Port-Joinville that we learn that the imaginary character Dino Egger of the book of the same name was born from the real people Dina Egger et Nino Egger, whose names Chevillard found on a gravestone. He later received a letter from a person who had known Dina Egger, who had died tragically: from fiction, reality.

For someone who seems asocial (can't drive, doesn't have a mobile phone and turns down many invitations) Chevillard seems to get about a great deal, has visited many places and appears to be more 'normal' than one might imagine, has had couscous with Marie NDiaye and her partner Jean-Yves Cendrey in Berlin, etc. He sends his daughters up the Tour Eiffel (but backs out himself as he's scared of heights) and goes on a bateau-mouche (the horror of many French people!) with them, and even states that tourist features are comforting, like a local form of universal gravitation!

Warning: Monotobio is full of delights, far too many to mention. Enjoy this fascinating book, but don't expect anything sequential, logical or even much which on the surface makes a great deal of sense: this is a book for those already converted by Chevillard's absurdities, and for those who will recognise things already mentioned in previous books. This is Chevillard at his best (not that there's ever a worst), but if you aren't already acquainted with him there is very little for you, apart perhaps from almost total incomprehension.

There's a catch of course, but then what do you expect from a Minuit writer, especially of Chevillard's nature? Chevillard hates narrative conventions, hates writing that follows on, so this is not the story of the novelist's life, or rather not a conventional story. Here we have memories, floods of them, apparently totally insignificant incidents such as (accidentally) scalding an earwig, drowning an ant, deliberately truncating a lizard's tail to watch the cut part wriggle for a few seconds but slowly grow back on the reptile again as a (surely misconceived?) lesson to his daughters; but then Chevillard, who bizarrely sees himself as a variety of vegetarian (is that a joke?), in spite of his obvious love of the animal kingdom, in spite of his sympathy for the exotic spider who briefly shares his room, loves eating animals. But I digress.

Monotobio is a book in which we learn by installments, in no obvious chronological order, of Chevillard's life as if through stream of consciousness or internal monologue, although of course there are many omissions he chooses to make, although you'll no doubt never know which. But you will learn of his marriage to Cécile, of his daughters Agathe (first) and then (around the same time of his father Bernard's death) of the birth of Suzie, his siblings and his friends. His parents have/had a holiday home on L'Île d'Yeu just off the Vendée coast, where the family go every summer, and here we learn of lot of the island.

We are told of course of many of Chevillard's books being published or in preparation, and it's in the cemetery of Port-Joinville that we learn that the imaginary character Dino Egger of the book of the same name was born from the real people Dina Egger et Nino Egger, whose names Chevillard found on a gravestone. He later received a letter from a person who had known Dina Egger, who had died tragically: from fiction, reality.

For someone who seems asocial (can't drive, doesn't have a mobile phone and turns down many invitations) Chevillard seems to get about a great deal, has visited many places and appears to be more 'normal' than one might imagine, has had couscous with Marie NDiaye and her partner Jean-Yves Cendrey in Berlin, etc. He sends his daughters up the Tour Eiffel (but backs out himself as he's scared of heights) and goes on a bateau-mouche (the horror of many French people!) with them, and even states that tourist features are comforting, like a local form of universal gravitation!

Warning: Monotobio is full of delights, far too many to mention. Enjoy this fascinating book, but don't expect anything sequential, logical or even much which on the surface makes a great deal of sense: this is a book for those already converted by Chevillard's absurdities, and for those who will recognise things already mentioned in previous books. This is Chevillard at his best (not that there's ever a worst), but if you aren't already acquainted with him there is very little for you, apart perhaps from almost total incomprehension.

20 August 2020

Le Dragon de Calais in Calais, Pas-de-Calais (62)

François Delarozière was born in Marseille in 1963, is the artistic director of the company La Machine, and is particularly known for Machines de l'île de Nantes, part of a re-generation project. He has also worked on Les animaux de la place in Roche-sur-Yon, a temporary project involving two giant 'spiders' in Liverpool in 2008 (when the city was named at the European capital of culture), plus a number of other things. One of those is Le Dragon de Calais, which at the time of my visit wasn't in operation, although it made photography better as I strive not to include people in my photos.

A juvenile seagull, no doubt on the lookout for tourist crumbs, waits patiently (but fruitlessly: a wise sign signals that it is forbidden to feed them).

A juvenile seagull, no doubt on the lookout for tourist crumbs, waits patiently (but fruitlessly: a wise sign signals that it is forbidden to feed them).

18 August 2020

Nicolas Appert in Châlons-en-Champagne, Marne (51)

Nicolas Appert was born in Châlons-en-Champagne in 1749 and became a confectioner in Paris in 1784. From 1794 he became involved in the process of conserving foods for a long period by heating them in hermetically sealed containers to eradicate bacteria from them. The process bacame known as appertisation.

Continuing his experiments he from 1815 became the initiator of techniques for conserving wines and milk, later perfected by fermentation by Louis Pasteur. Several times Appert was acknowledged by the Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie nationale, although his techniques were advanced by English developers of his technique without any compensation/recognition for Appert and he was buried in an ossuary in 1841.

This monument was erected in 2009.

Continuing his experiments he from 1815 became the initiator of techniques for conserving wines and milk, later perfected by fermentation by Louis Pasteur. Several times Appert was acknowledged by the Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie nationale, although his techniques were advanced by English developers of his technique without any compensation/recognition for Appert and he was buried in an ossuary in 1841.

This monument was erected in 2009.

17 August 2020

Albert Camus in Villeblevin, Yonne (89)

Camus celebrated the New Year of 1960 in his house in Lourmarin (Vaucluse) with his family and friends Janine and Michel Gallimard and their daughter Anne. Camus's wife Francine and their two children left by train for Paris, whereas Camus chose (or was strongly invited) to join the Gallimards in their (faulty?) Facel Vega (FV3B), and after stopping off for the night at a hotel in Thoissey (Ain) the car (travelling at 180 km per hour (!)) hit a few plane trees near Villeblevin and the débris from the car was scattered over a wide area. Camus died instantly, Michel died six days later, but the women in the back only suffered minor injuries.

Camus's monument stands very close to the Mairie in Villeblevin.

Camus's monument stands very close to the Mairie in Villeblevin.

Marie-Angélique le Blanc in Songy, Marne (51)

Marie-Angélique Memmie le Blanc (c. 1712-75) was born in what is now Wisconsin (USA), an American Indian famous for being an 'enfant sauvage' like Victor (made famous by Truffaut in the film L'Enfant sauvage) and Kaspar Hauser (also made famous by Hertzog in the film The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. There's a difference though: the Marie-Angélique story seems to have been based on truth, but the others probably not. In L'énigme des enfants-loups : une certitude biologique mais un déni des archives, 1304-1954 (2007), Serges Aroles (an expert on feral children) argues strongly in favour of the truth of the story.

Marie-Angélique (sent to France in 1720) escaped from the plague in Provence and survived for ten years on leaves and roots before being captured in the woods in Songy in 1731. Following her capture she learned to read and write, was welcomed by royalty, and oh the story is too long to go into here but she died far from being penniless.

The plaque by the statue in Songy states that it was erected in 2009, and that Marie-Angélique was baptised in 1732 at L'Église Saint-Sulpice in Châlons-en-Champagne.

Marie-Angélique (sent to France in 1720) escaped from the plague in Provence and survived for ten years on leaves and roots before being captured in the woods in Songy in 1731. Following her capture she learned to read and write, was welcomed by royalty, and oh the story is too long to go into here but she died far from being penniless.

The plaque by the statue in Songy states that it was erected in 2009, and that Marie-Angélique was baptised in 1732 at L'Église Saint-Sulpice in Châlons-en-Champagne.

15 August 2020

Wilfred Owen, Ors, Nord (62)

La Maison forestière was created in 2011, being the work of British artist Simon Patterson helped by the architect Jean-Christophe Denise. It is dedicated to the work of the poet Wilfred Owen, and inside the house (closed at the year of our visit) are Owen's poems on the walls. The cellar, where he wrote his last letter to his mother, has been kept intact. Owen spent his last night here.

Owen was killed on 4 November 1918 while trying to cross the Sambre canal which goes through Ors: his parents learned of his death on 11 November, after armistice had been declared. An interpretation panel here says that Owen's work in general can be seen as an 'Anthem to Doomed Youth'.

Very, very weirdly, the Bureau de Tourisme Cambresis says Owen, although unknown in France, is the most researched poet in the UK after Shakespeare. Yeah, keep taking the tablets.

Wilfred Owen is buried in Ors Communal Cemetery.

On the way to Ors British Cemetery we found a herd of cows, clustering together as if for protection. None of them seemed particularly happy, and I thought of them somehow knowing what their fate will be, just like the innocent soldiers going to war knew what their fate would be. Working-class soldiers reared to be slaughtered, cattle too, what's the difference? No point in arguing that animals don't produce poetry: these creatures are poetry.

Owen was killed on 4 November 1918 while trying to cross the Sambre canal which goes through Ors: his parents learned of his death on 11 November, after armistice had been declared. An interpretation panel here says that Owen's work in general can be seen as an 'Anthem to Doomed Youth'.

Very, very weirdly, the Bureau de Tourisme Cambresis says Owen, although unknown in France, is the most researched poet in the UK after Shakespeare. Yeah, keep taking the tablets.

Wilfred Owen is buried in Ors Communal Cemetery.

On the way to Ors British Cemetery we found a herd of cows, clustering together as if for protection. None of them seemed particularly happy, and I thought of them somehow knowing what their fate will be, just like the innocent soldiers going to war knew what their fate would be. Working-class soldiers reared to be slaughtered, cattle too, what's the difference? No point in arguing that animals don't produce poetry: these creatures are poetry.

14 August 2020

Water Tower art in Montliot-et-Courcelles, Côte-d'Or (21)

It's not unusual for places to decorate their water towers, as in the States for instance, although I found this one in Montliot-et-Courcelles, Côte-d'Or (21) particularly well done, and not at all cutesy. A goldfinch with an acorn in its beak above squirrels on one side, a kid tickling a blue tits' nest on the other. Just one example among millions why the fake English government desperately clinging onto power want to prevent people from discovering France.

13 August 2020

Antoinette Quarré in Dijon, (Côte-d'Or (21))

Antoinette Suzanne Quarré (1813-47) was a working-class poet who was born in Recey-sur-Ource (Côte-d'Or) and died in Dijon. She was a linen maid in Dijon of poor health, and a story handed down tells that she learned to read from Voltaire's Zaïre. Receiving lessons from M. de Belloguet, she leaned towards poetry and published several works in verse and in prose (particularly in Le Journal des Demoiselles). An elegy on Marie d'Orléans gave her a mention in the Société des lettres et des arts de Seine-et-Oise in 1839. She sent her verses to Lamartine, who in 1838 responded by a poem, 'À une jeune fille poète', which he included in Recueillements poétiques. Encouraged by friends she published a collection of poetry in 1843, although she died of heart failure in 1847.

Gloria Friedmann in Dijon, (Côte-d'Or (21))

Gloria Friedmann (born in 1950) constructed this piece, Le Compteur du temps, in 2020, in which the times of several places around the world can be seen. The message at the bottom of the sculpture states that what really counts is one's own time, that inside us at this precise moment, and that we should take advantage of it. We shouldn't forget that it's not time which passes, but us who pass in time.

Buffon in Montbard, (Côte-d'Or (21))

Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon (1707-1788) was a naturalist, mathematician, biologist, cosmologist, philosopher and writer who influenced Lamarck and Darwin, and was called 'the Pliny of Montbard'. His Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière (1749-1804), in 44 volumes (eight posthumous) is one of the most important scientific works of the time. The Parc Buffon, which is linked to a former castle owned by the Dukes of Burgundy, was built by Buffon between 1733 and 1742. The park contains Buffon's Cabinet de travail, where he spent many hours writing his huge work.

The two towers, Aubespin and Saint-Louis, are part of the remains of the castle and date from the 14th century, although Buffon rebuilt the Tour de Saint-Louis as a summer study first and then as a laboratory and library. L’église Saint-Urse is also a vestige of the old castle, and Buffon is buried in a chapel in it.

Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton (1716-1799) was born in Montbard and was Buffon's colleague: the first fifteen volumes of L’Histoire Naturelle names Daubenton as a 'co-author'.

The museum was unfortunately closed at the time we went.

Buffon's cabinet de travail, with plaque above noting Jean-Jacques Roussean's visit here.

La Tour de l'Aubespin.

La Tour de Saint-Louis.

The monument to Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton.

L’église Saint-Urse.

And the chapel where Buffon's remains lie.

The two towers, Aubespin and Saint-Louis, are part of the remains of the castle and date from the 14th century, although Buffon rebuilt the Tour de Saint-Louis as a summer study first and then as a laboratory and library. L’église Saint-Urse is also a vestige of the old castle, and Buffon is buried in a chapel in it.

Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton (1716-1799) was born in Montbard and was Buffon's colleague: the first fifteen volumes of L’Histoire Naturelle names Daubenton as a 'co-author'.

The museum was unfortunately closed at the time we went.

Buffon's cabinet de travail, with plaque above noting Jean-Jacques Roussean's visit here.

La Tour de l'Aubespin.

La Tour de Saint-Louis.

The monument to Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton.

L’église Saint-Urse.

And the chapel where Buffon's remains lie.