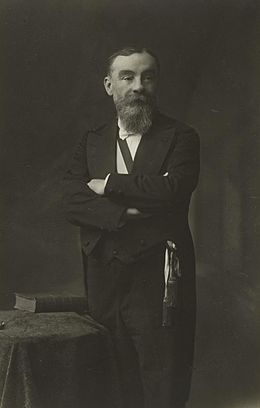

Hector Bianciotti (1930–2012) was born in Argentina and was a film actor, a journalist, a writer and an academic who took on French nationality. He lived in from 1961 and in 1969 Maurice Nadeau published his first literary criticisms in La Quinzaine littéraire. He also wrote novels in his maternal language, although his first novel in French, Sans la miséricorde du Christ (1985), won the prix Femina. After his death Dany Laferrière took his seat at the Académie française.

27 September 2017

Paris 2017: Cimetière de Vaugirard: Hector Bianciotti

Hector Bianciotti (1930–2012) was born in Argentina and was a film actor, a journalist, a writer and an academic who took on French nationality. He lived in from 1961 and in 1969 Maurice Nadeau published his first literary criticisms in La Quinzaine littéraire. He also wrote novels in his maternal language, although his first novel in French, Sans la miséricorde du Christ (1985), won the prix Femina. After his death Dany Laferrière took his seat at the Académie française.

26 September 2017

Cimetière du Mesnil-le-Roi, Yvelines (78) #5: Jeanne and André Bourin

Jeanne Bourin (1922–2003) (née Mondot), was a historical novelist who returned to the Catholic faith at the age of forty. She had a sentimentalised and idealised view of the Middle Ages, and her La Chambre des dames (1979) is her most well-known novel. She married the literary critic and writer André Bourin (1918–2016) in 1940. André contributed to a number of magazines and wrote at least thirteen books.

Cimetière du Mesnil-le-Roi, Yvelines (78) #4: Louis Pauwels

'Quand verrai-je ma fin du monde ?

Que votre Volonté soit faite etnon la mienne.

Mais je vourdrais semer des oiseaux dans ceux que j'aime

Et qu'ils ne souffrent pas quand je m'endormirai.'

Louis Pauwels (1920–1997) was, as the stone above states, a poet, writer and journalist. He was the editor-in-chief of Combat in 1949, directed the monthly Marie-France, and with Jacques Bergier founded the magazine Planète, dedicated to science, philosophy and esotericism. He later founded Figaro Magazine, which he was in charge of for more than twenty years. The novel L'Amour monstre (1954) is one of his principal fictional works.

Cimetière du Mesnil-le-Roi, Yvelines (78) #3: Józef Czapski

Cimetière du Mesnil-le-Roi, Yvelines (78) #2: Zofia and Zygmunt Hertz

Zofia Hertz (1911–2003) was the first Polish woman to become a lawyer. She met Jerzy Giedroyc in 1933 at the Bureau de la culture, de la presse et de la propagande and she became his secretary. With Jerzy Giedroyc and her husband Zygmunt (1908–79), she also founded the Instytut Literacki (which in two years produced twenty-eight publications) and Kultura in 1946.

Cimetière du Mesnil-le-Roi, Yvelines (78) #1: Jerzy Giedroyc

I showed a photo of a plaque dedicated to Jerzy Giedroyc (1906–2000) a few posts below, and now I discover him in the Cimetière du Mesnil-le-Roi. As I mentioned in the post, he was the founder of the review Kultura, a magazine which concerned Polish culture, particularly emigrant writers and intellectuals. He also founded the literary institute in Maisons-Laffitte. Following his wishes, Kultura ceased publication on his death.

24 September 2017

Marie-Hélène Lafon: Sur la photo (2003)

Rémi lives in Paris with his wife Isabelle and daughter Louise, and is a collector of photos. This novel weaves in and out of Rémi's present life and his life as an eleven-year-old with teenaged sisters in the countryside. Maybe I wasn't quite ready for it, but I was certainly expecting more of this highly-rated novelist: OK, this is one of her earlier works, so I'll return to her.

Links to my Marie-Hélène Lafon posts:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Marie-Hélène Lafon: Le Pays d'en haut : entretiens avec Fabrice Lardreau

Marie-Hélène Lafon: Sur la photo

Marie-Hélène Lafon: Les Derniers indiens

Marie-Hélène Lafon: L'Annonce

Links to my Marie-Hélène Lafon posts:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Marie-Hélène Lafon: Le Pays d'en haut : entretiens avec Fabrice Lardreau

Marie-Hélène Lafon: Sur la photo

Marie-Hélène Lafon: Les Derniers indiens

Marie-Hélène Lafon: L'Annonce

22 September 2017

Jerzy Giedroyc in Maisons-Laffitte, Yvelines (78)

'Jerzy GIEDROYC

1906–2000

Fondateur de « Kultura »

revue politique polonaise –

et de l'Institut Littéraire

a vécu et travaillé

dans cette maison'

Kultura was a Polish and world cultural magazine designed as an instrument against communist totalitarianism. Many important writers of the twentieth century contributed to it, such as Albert Camus, Simone Weil, George Orwell, Witold Gombrowicz, T. S. Eliot, Emil Cioran and Czesław Miłosz.

Paris 2017: Cimetière de Montrouge, Hauts-de-Seine (92) #2: Michel Audiard

Michel Audiard (1920–85) was a screen writer, a film director, and a novelist. Sometimes called a right-wing anarchist, one of his greatest regrets was not to have adapted Céline's Voyage au bout de la nuit to film. He is the father of the film director Jacques Audiard. His novels include Priez pour elle (1950), Massacre en dentelles (1952), Ne nous fâchons pas (1966), Le Terminus des prétentieux (1968), and Le Petit cheval de retour (1975).

Ariane Chemin: Mariage en douce (2016)

Ariane Chemin works for Le Monde, and this book involves the secret marriage of diplomat and (amusingly fraudulent) two-times winning Goncourt, the chameleon Romain Gary, man of a number of names, to Jean Seberg, the deeply disturbed female actor most famous for her role in Godard's hugely popular À bout de souffle (Breathless in English).

The heavily-cropped photo on the cover shows the happy couple looking perhaps not all that happy: the tiny village Sarrola in Corsica was chosen for the occasion – and the mountains can clearly be seen in the background – because they (and Gary especially) wanted to avoid a media circus at all costs.

However, this book is also a summary of the lives of Gary and Seberg, Gary the Vilnius-born possessor of many names, Seberg the small-town, Marshalltown, Iowa-born movie star. I loved the information about them visiting the Kennedys, and Jackie Onassis telling Jean Seberg (aside) not to get married as it ruins things. De Gaulle and his wife would certainly have objected, but then De Gaulle and America...

Jean Seberg went on to marry twice after her marriage to Gary (although her final marriage was bigamous) before killing herself 30 August 1979. Gary put a gun to his mouth on 2 December 1980, leaving a note that his suicide had nothing to do with Seberg. Really, nothing at all?

The heavily-cropped photo on the cover shows the happy couple looking perhaps not all that happy: the tiny village Sarrola in Corsica was chosen for the occasion – and the mountains can clearly be seen in the background – because they (and Gary especially) wanted to avoid a media circus at all costs.

However, this book is also a summary of the lives of Gary and Seberg, Gary the Vilnius-born possessor of many names, Seberg the small-town, Marshalltown, Iowa-born movie star. I loved the information about them visiting the Kennedys, and Jackie Onassis telling Jean Seberg (aside) not to get married as it ruins things. De Gaulle and his wife would certainly have objected, but then De Gaulle and America...

Jean Seberg went on to marry twice after her marriage to Gary (although her final marriage was bigamous) before killing herself 30 August 1979. Gary put a gun to his mouth on 2 December 1980, leaving a note that his suicide had nothing to do with Seberg. Really, nothing at all?

21 September 2017

Paris 2017: Cimetière parisien de Bagneux, Hauts-de-Seine (92) #1: J.-H. Rosny aîné

J.-H. Rosny aîné was the pseudonym of Joseph Henri Honoré Boex (1856–1940), a French author of Belgian origin who is considered one of the founding figures of modern science fiction. Born in Brussels, Rosny spent most of his years in France. Rosny was an influence on Arthur Conan Doyle, the plot of his Force mystérieuse (1913) being adopted by Doyle for his The Poisoned Belt. Les Navigateurs de l'infini (1925) is generally considered as Rosny's best work, and his use of the word 'astronautique' is a first. However, I suspect that, in spite of a prize existing in his name, Rosny will be most remembered for his disagreements with Lucien Descaves, particularly for the, er, scandalous winning of the Goncourt in 1932 by Guy Mazeline's Les Loups, rather than Céline's Voyage au bout de la nuit, which received the 'compensatory' Renaudot.

Paris 2017: Cimetière parisien de Bagneux, Hauts-de-Seine (92) #2: Anna Langfus

Anna Langfus (1920 – 1966) won the prix Goncourt in 1962 (for Les Bagages de sable), and this is one of the few Goncourt graves I've come across to mention the Goncourt. But it certainly should be mentioned, if only because (at the time that I write) there have been only twelve female winners of the title since its creation in 1901. Langfus was a Polish Jew, and Les Bagages de sable concerns the difficulties of a Shoah survivor adapting to everyday circumstances.

My Anna Langfus posts:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Jean-Yves Potel: Les Disparitions d’Anna Langfus

Anna Langfus: Les Bagages de sable | The Lost Shore

Anna Langfus: Cimetière parisien de Bagneux, Hauts-de-Seine

Paris 2017: Cimetière de Montmartre, 18e arrondissement #3 Émile de Girardin

Émile de Girardin (1806–81) was the founder of the paper La Presse, and, with his rival Armand Dutacq (Le Siècle) was responsible for the first serial novels to appear, some writers of note being Balzac, Lamartine and George Sand. He was also a politician and wrote numerous political and social works.

20 September 2017

Éric Holder: Mademoiselle Chambon (1996)

Before reading – indeed before knowing the existence of – the novel on which the movie is based, I'd seen that film. And I loved it. But for me this is an unusual case of loving the film (by Stéphane Brizé) although not feeling the same way about the book.

I have no problems at all with Éric Holder's short book, which in so many ways manages to pack in so more (in one hundred and fifty-seven pages) than the film, but the film manages to say so much more in a very short space, with a far more limited number of characters, without actually stating feelings, just leaving the unspoken to be said in images. Also, the two main characters in the book (the Portuguese manual worker Antonio and the school teacher Véronique Chambon) are roughly half the age of their counterparts in the film, which seems far more appropriate for the circumstances.

The story (in both novel and film) is about Antonio and Véronique, who come together (but never sexually) through Kevin, Antonio's son by his wife Anne-Marie. After the film, I found too much extraneous detail here, particularly in Antonio's workplace, the petty rivalry, and Antonio being under pressure to fall in with his boss Van Hamme's wishes.

Oh for the aching, gloriously ferocious non-dits of the film, I thought. Which all the same in no way discourages me from reading any more of Éric Holder's work.

The film Mademoiselle Chambon:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Stéphane Brizé's Mademoiselle Chambon

My other post on Éric Holder:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Éric Holder: L'homme de chevet

I have no problems at all with Éric Holder's short book, which in so many ways manages to pack in so more (in one hundred and fifty-seven pages) than the film, but the film manages to say so much more in a very short space, with a far more limited number of characters, without actually stating feelings, just leaving the unspoken to be said in images. Also, the two main characters in the book (the Portuguese manual worker Antonio and the school teacher Véronique Chambon) are roughly half the age of their counterparts in the film, which seems far more appropriate for the circumstances.

The story (in both novel and film) is about Antonio and Véronique, who come together (but never sexually) through Kevin, Antonio's son by his wife Anne-Marie. After the film, I found too much extraneous detail here, particularly in Antonio's workplace, the petty rivalry, and Antonio being under pressure to fall in with his boss Van Hamme's wishes.

Oh for the aching, gloriously ferocious non-dits of the film, I thought. Which all the same in no way discourages me from reading any more of Éric Holder's work.

The film Mademoiselle Chambon:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Stéphane Brizé's Mademoiselle Chambon

My other post on Éric Holder:

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Éric Holder: L'homme de chevet

Bernard-Marie Koltès: Dans la solitude des champs de coton | In the Solitude of Cotton Fields (2010)

Bernard-Marie Koltès (1948–89) died of AIDS three years after the publication of this play, Dans la solitude des champs de coton (trans. as In the Solitude of Cotton Fields), which is a mere sixty short pages long. Maybe 'play' is a misnomer, as it's really a dialogue between the Dealer and the Customer. But no transaction takes place as the whole thing is a tense verbal ballet, skirting around a never specifically mentioned subject, although drugs are briefly mentioned, and sex a number of times. There's also an atmosphere of threat, of danger, of a kind of known but at the same time uncharted territory, of braving an unspoken challenge. I can't say more now as this is the only work I've yet read by Bernard-Marie Koltès, whose existence I only discovered last year on finding his grave in the Cimetière de Montmartre:

My other Bernard-Marie Koltès posts:

Yves Ravey: Enlèvement avec rançon (2010)

Yves Ravey's Enlèvement avec rançon is a kind of thriller (but only a kind of) and is exactly what it says on the cover: a kidnapping with ransom. This is first person narration, and that person is Max, the elder brother of Jerry, whom he has not seen for twenty years (when Jerry was twenty and Max fifteen). What happened to Max in those twenty years seems very little, and Max (in spite of some obvious sexual dalliances) is still in the home of his widowed mother, now in an old people's complex Max is paying for.

As for Jerry, who has come from Afghanistan, there are obvious suggestions of Islamisation: he doesn't like eating pork (including lard with fried eggs which he used to love), and appears to be only interested in making money for a mysterious organisation.

Max has stomached twenty-two years as an accountant to Pourcelet, a highly unsympathetic boss. So why shouldn't he profit from him by (with Jerry) kidnapping his daughter Samantha and demanding half a million euros ransom money?

Well, this may be a hare-brained idea, but it may come off, although it of course doesn't allow for sibling rivalry, or (perish the thought) Stockholm syndrome. Crime (whisper it gently) often does pay, but that payment might come at a high price. This is Yves Ravey, and his books resist being put down.

My other posts on Yves Ravey:As for Jerry, who has come from Afghanistan, there are obvious suggestions of Islamisation: he doesn't like eating pork (including lard with fried eggs which he used to love), and appears to be only interested in making money for a mysterious organisation.

Max has stomached twenty-two years as an accountant to Pourcelet, a highly unsympathetic boss. So why shouldn't he profit from him by (with Jerry) kidnapping his daughter Samantha and demanding half a million euros ransom money?

Well, this may be a hare-brained idea, but it may come off, although it of course doesn't allow for sibling rivalry, or (perish the thought) Stockholm syndrome. Crime (whisper it gently) often does pay, but that payment might come at a high price. This is Yves Ravey, and his books resist being put down.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Yves Ravey: La Fille de mon meilleur ami

Yves Ravey: Un notaire peu ordinaire

Yves Ravey: Trois Jours chez ma tante

19 September 2017

Alain Poulanges: Boby Lapointe : ou les mamelles du destin (2012)

Boby Lapointe (1922–1972), about whom I have written several posts on this blog, was a singer, writer and mathematician of some brilliance. He was born and died in Pézenas (Hérault), although he spent most of his mature years in Paris. Alain Poulange's biography is by far the best work that has been written on Boby, although – five years after its publication – it is out of print. Which is a pity, as he seems to be more popular today than he was in his lifetime, and only several weeks ago Le Monde included him in their Géants de la chanson series.

Boby's singing involves great use of puns and other play on words, Spoonerisms, nonsense, general absurdity, and it is perhaps unsurprising that a number of people have found his work too difficult to understand, although to contradict this many children have also enjoyed his playfulness. Even just after the age of twenty he was using a pun in a very serious situation: he escaped from the Nazi work camp (Service du Travail Obligatoire, usually called STO) and made his way back to Pézenas as Robert Foulcan (for which read fout le camp, which of course is exactly what he was doing).

The book charts his love of women, his love of wine, his sense of humour, and his inability to deal with money. He was very fortunate to have Georges Brassens (who too didn't care much for money, although he had enough of it) change his bald car tyres for new ones, even give him a new car and help his family out.

There are many humorous moments in this book, such as the attempts to take a plaster cast of his penis, or the fact that (as Pierre Perret notes in the Preface) he could even joke about dying of cancer: usually late for gigs, he suddenly as if by miracle started turning up early for them: when other performers took a long time getting to a venue because of the difficulty parking, Boby simply parked on the pavement: his reasoning was that he wouldn't have to pay the fines because he'd be dead.

We're lucky to have this book. But why hasn't it been re-printed?

My other Boby Lapointe posts:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Birth and Death of Boby Lapointe in Pézenas, Hérault (34)

Musée Boby Lapointe, Pézenas, Hérault (34)

Boby Lapointe Sculptures in Pézenas, Hérault (34)

Boby's singing involves great use of puns and other play on words, Spoonerisms, nonsense, general absurdity, and it is perhaps unsurprising that a number of people have found his work too difficult to understand, although to contradict this many children have also enjoyed his playfulness. Even just after the age of twenty he was using a pun in a very serious situation: he escaped from the Nazi work camp (Service du Travail Obligatoire, usually called STO) and made his way back to Pézenas as Robert Foulcan (for which read fout le camp, which of course is exactly what he was doing).

The book charts his love of women, his love of wine, his sense of humour, and his inability to deal with money. He was very fortunate to have Georges Brassens (who too didn't care much for money, although he had enough of it) change his bald car tyres for new ones, even give him a new car and help his family out.

There are many humorous moments in this book, such as the attempts to take a plaster cast of his penis, or the fact that (as Pierre Perret notes in the Preface) he could even joke about dying of cancer: usually late for gigs, he suddenly as if by miracle started turning up early for them: when other performers took a long time getting to a venue because of the difficulty parking, Boby simply parked on the pavement: his reasoning was that he wouldn't have to pay the fines because he'd be dead.

We're lucky to have this book. But why hasn't it been re-printed?

My other Boby Lapointe posts:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Birth and Death of Boby Lapointe in Pézenas, Hérault (34)

Musée Boby Lapointe, Pézenas, Hérault (34)

Boby Lapointe Sculptures in Pézenas, Hérault (34)

Cimetière nouveau de Neuilly, Hauts-de-Seine (92) #:9 Jean Aragny

Jean Aragny (1898–1939) was a playwright about whom little information seems readily available, apart from his writings, seems to be known. His plays include Les Yeux du spectre (1924), Prime (1932), and Bourreaux d'enfants (1939). He also wrote the screenplay adaptation of Timothy Shea's novel Toute sa vie (1930), the screenplay of Les vacances du diable (1931), and co-wrote the screenplay for Le Poignard malais (1931).

18 September 2017

Cimetière nouveau de Neuilly, Hauts-de-Seine (92) #8: Victor Charbonnel

Victor Charbonnel (1863–1926) was a priest who left the priesthood and then gave a series of anti-clerical talks. Among a number of other publications he wrote Séparation de l'Eglise et de la famille (1900), Victor Charbonnel: Sensations de vie (1906), and La Vérité sur le Vatican: Palais et caverne [1907]. In 1901 he founded the paper La raison and was a director of L'Action with Henry Bérenger.

Karl Wood's Baker Street Windmill. Orsett, Essex, UK

David Skelton of New Zealand sends me this superb shot of Karl Wood's oil painting of a smock mill which he rescued from oblivion. It's dated 1933 and Guy Blythman has identified it as Baker Street mill, Orsett, Essex. This is now a grade II listed building, and is partly a house conversion. Many thanks to both David Skelton and Guy Blythman for this.